COURTESY / FGJE

The Indigenous pipeline fighters of Turtle Island have become a darling of the global climate justice movement. Leading more than a decade of civil disobedience to halt construction of private infrastructure threats to, air, water and territory, land-based rural people of North America have been among the first and worst affected by these megaprojects.

Thousands have been shot, bombed, gassed, beaten, bound, strip-searched, caged and fined for direct action to demand governments obey their own treaty and environmental laws. From Canada through the United States and into Mexico, defenders have been on the frontlines, speaking out or bearing witness for cultural survival, Mother Nature and her yet unborn.

The trauma experienced by peaceful water protectors and prayerful intentional communities at the hands of the state apparatus employed to militarily repress the unrest is mounting as the struggle deepens. Members of the media exposing the conflict are as apt as standard-bearers to be treated like criminals in the field and in the courts. The vulnerability of remote communities to pandemic disease introduced by outside workforce settlements creates a public health risk. Their temporary man-camps bring in illegal sex and drug trafficking.

Worse is the menace of a future that accelerates the race to the bottom on the quality-of-life scale. More megaprojects could proceed without local consultation – a recipe for failure in the search for sustainability. More oil fracking and global greenhouse gas emissions would sully the scene. More toxic spills would increase the already 1,000-fold rate of species extinction. More sacred sites and historical treasures would be forever razed.

The grassroots anti-pipeline movement advocates for a return to values of respect and harmony with our surroundings. It promotes state-of-the-art legal strategies to restore time-honored relationships of balance between humans and other living things. It demonstrates ecologically-friendly paths for resilience that rely on low-impact fuel use and waste reduction. It embraces traditional wisdom, spirituality, and native cosmology. Having been eschewed by politicians, it has followed the Gandhi-inspired route into the streets. It has morphed to focus divestiture campaigns on banks that finance pipelines.

Yet, even after weathering the past federal administrations’ decidedly anti-rights positions and ushering in more-progressive national governments on the northern continent, the groundswell of support for protection of natural and human resources from the destruction caused by pipelines faces vastly unequal power relations in the fight for environmental justice.

Throughout Indian country, communities are fending off weaponized and illegal incursion – from the fracking fields of the Native Athabascan boreal forest in Canada’s Alberta Province, to the construction sites of Line 3 at Mississippi River Headwaters in Anishinaabe treaty territory; from Line 5 in the U.S.-Canada boundary waters at the Straits of Mackinac, to the Dakota Access Pipeline crossing of the Missouri River in Lakota lands; from the Bayou Bridge Pipeline trespass in St. James Parish, Louisiana at the Gulf of Mexico, to locations on the Texas-Mexico border and on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.However, nowhere is the strife more painful than in the Indigenous Yaqui territory of Sonora. In this Mexican state on the northern border, human rights defenders who oppose pipelines have to choose between self-exile or the likely outcome of imprisonment, kidnapping, disappearance, and murder. As casualties mount in a more-than decade-long water war, the Yaqui have become a leading tribe in the U.N. process for countries around the world to require “free, prior, and informed consent” from Indigenous peoples facing megaprojects.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t translate to safety on the ground. In July, Indigenous Peoples Rights International called for a “cease fire” in the wake of 20 forced Yaqui disappearances. “The Yaqui people have been one of the great role models in the struggles of indigenous peoples in Mexico for the defense of their collective rights … and, for several years now, they have been facing increasing violence,” said the non-profit watchdog.

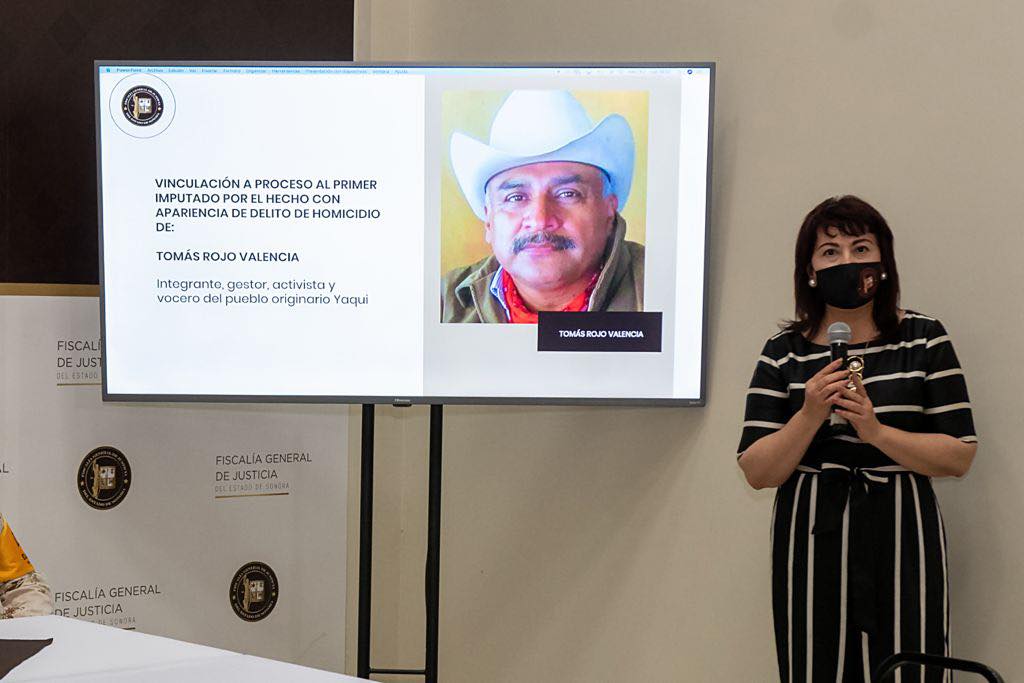

The plea to the Mexican government and the international community coincided with the Sonora State Attorney General’s Office announcement of its incarceration of a second material suspect in the alleged premeditated murder of beloved Yaqui pipeline fighter and tribal spokesperson, Tomás Rojo Valencia, who disappeared May 27. Sonora Prosecutor Claudia Indira Contreras Córdoba announced recovery of his body June 21, with the first murder suspect taken into custody on July 5. A hammer considered the murder weapon was found with the deceased in a clandestine roadside grave.

The Yaquis’ eight villages — enshrined in history for never accepting defeat by any colonial power — have been holding off a water pipeline and a gas pipeline during the last two six-year governorships. In the case of the water pipeline, the Independence Aqueduct, the tribe presented a 1940 presidential decree recognizing Yaqui jurisdiction and rights to 50 percent of the Yaqui River water. In 2013, the tribe obtained federal Supreme Court reversal of the megaproject’s approval. . The high court ordered construction halted at least until after proper consultation via an environmental impact statement process.

Former Gov. Guillermo Padrés Elías, backed by then-President Felipe Calderon, promoted the aqueduct for urban industrial expansion of big businesses such as Apasco, Ford, Tecate, Coca-Cola, Big Cola, and Pepsi. Its corollary impact would be to appease foreign export marketeers by drying up the Yaqui Valley, which produces 30 percent of Mexico’s food. Yaqui tribal spokesperson Mario Luna Romero told state authorities that the slated diversion of nearly 20 billion gallons of water a year would cause a loss of more than half the Yaqui wheat production, not to mention degradation of drinking water due to reduced recharge of aquifers.

When the Padrés administration ignored the Supreme Court decision, the Yaqui tribe blockaded Federal Highway 15, a major trade artery running through their lands on its way between Mexico City and the Nogales international border crossing. Rojo Valencia was active in the Yaqui Defense Brigade that established toll booths to fund the resistance until Padrés put out a warrant for him. Fearing he would be deprived of due process of law, he begrudgingly took refuge in Mexico City.

A new governor and a new president nonetheless failed to protect him – and other indigenous land rights advocates across the country. Since January, 14 Indigenous land and water defenders have been killed . In addition to Rojo Valencia, Native leaders who met their demise in unresolved cases by mid-2021 are Simón Pedro Pérez López, Jaime Jiménez Ruiz, Fidel Heras Cruz, Raymundo Robles Riaño, Noé Robles Cruz, Gerardo Mendoza Reyes, María Eufemia Reyes Esquivel, Vicente Guzmán Reyes, Ambrosio Guzmán Reyes, José Luis Chávez Mondragón, Manuel Carmona Esquivel, Agustín Valdez, and Luis Urbano Domínguez.

A group of Yaqui women in the village of Lomas de Bácum is asking support for their legal battle and campaign for return of seven missing local men they last saw in July en route to perform an annual religious ceremony. Grassroots prisoner advocates in Philadelphia conducted a letter-writing event in June for the release from Sonoran prison ofFidencio Aldama Pérez. The 33-year-old Yaqui father of two has already served 55 months of a 15-year sentence on what his wife and others claim are trumped up charges for his community’s opposition to the gas pipeline construction. A victory in court has also failed to stop illegal construction of the disputed gas pipeline through Yaqui territory. A federal court suspended construction of Sempra Energy’s gas-line megaproject, due to lack of Yaqui consent. However, the U.S. company continues to build it anyway.

Mario Luna Romero, who carries on as tribal spokesperson for the Yaqui tribe after having spent more than a year in prison under the Padrés regime, enlisted in the federal Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists in 2017. Two separate incidents in which his wife and his son were each forced off the roadway where they were driving prompted him to seek protection. That served to little avail, however. His family was attacked at home later the same year when assailants set fire to a car in the driveway. Since then, Luna has launched Namakasia Radio, joining the roster of the most precariously positioned journalists in Mexico – indigenous community broadcasters. His sister disappeared for five days this year.

Padrés made bail of $2.1 million in 2019, after two years in prison on charges of money laundering, tax fraud and organized crime, which remain to be litigated. Rojo’s family laid his body to rest in 2021 with a customary prayer and song at the traditional interment site for tribal war heroes in the Sierra del Bacatete.

“We recognize and treasure … the peaceful social struggle of our beloved Tomás, who has instilled in us … with great enthusiasm and love for his Indigenous blood … his great vision of asserting our rights as Indigenous peoples of the Yaqui nation,” the family said in a recorded statement.

It is incumbent on human rights defenders to honor that sacrifice and end the state of siege in Yaqui territory. Water protectors must unite and take action behind the demands of national and international organizations reflected in the recent U.N. call “to carry out an urgent and exhaustive investigation of the facts, and to carry out the appropriate search actions to locate the Yaqui people who are missing.”

Likewise, it is imperative to strengthen Mexico’s protection and prevention mechanism with culturally adapted security measures. More federal funding is needed, together with proactive cooperation at the state and local official levels — which are so far the target of most of the system’s beneficiary complaints.

Yet only by obtaining enforcement of the Indigenous communities’ right to free, prior, and informed consent on megaprojects will the harassment begin to wane.

Talli Nauman is an analyst on environmental affairs and access to information for the Americas Program and director of Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness.