The war against Mara Salvatrucha that President Donald Trump declared even before taking office has turned into a war against Central American immigrants in general. In an effort to stain the reputation of thousands of Latinos living in the United States and justify his anti-immigrant policies, Trump is exploiting the fear that the MS generates.

The war against Mara Salvatrucha that President Donald Trump declared even before taking office has turned into a war against Central American immigrants in general. In an effort to stain the reputation of thousands of Latinos living in the United States and justify his anti-immigrant policies, Trump is exploiting the fear that the MS generates.

Since his campaign, Trump has been promising his supporters “to destroy” the gang and deport its members, and all undocumented immigrants. Now, more than a year after moving into the White House, the president maintains his zero-tolerance rhetoric, while his policies make his rejection of the immigrant community even more evident.

“A few unusual cases that took place on Long Island have been generalized to create an image of the Latin foreigner as a threat,” said Óscar Chacón, director of Alianza Americas. “Trump uses this to justify the decision to end the Unaccompanied Minors, DACA and TPS programs.”

In recent speeches, Trump has tried to connect crimes committed by gang members with the much broader group of undocumented immigrants. During his State of the Union Address, for example, the president blamed a specific crime on the country’s immigration policies:

“Many of these gang members took advantage of glaring loopholes in our laws to enter the country as unaccompanied alien minors — and wound up in Kayla and Nissa’s high school,” Trump said in that January 31 speech. He later added, “Tonight, I am calling on the Congress to finally close the deadly loopholes that have allowed MS-13, and other criminals, to break into our country.”

Kayla Cuevas and Nissa Nickens were murdered on Long Island, New York, in November 2016 by members of MS-13 who attended the same school. Of the nine suspects arrested for the crime, only two were undocumented immigrants.

According to figures from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency arrested 1,095 suspected MS members and collaborators in 2016. However, only 162 of those detained were undocumented immigrants; the other 933 were U.S. citizens.

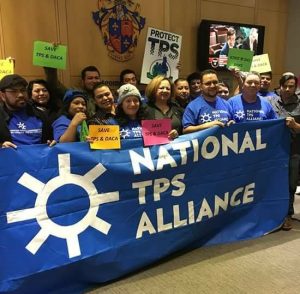

“Those of us in the TPS and DACA programs are the immigrants who are checked the most,” Cecilia Martínez, of the National TPS Alliance, told the Americas Program. “They review our records each year, they have our fingerprints on every document, and we have to undergo rigorous security measures to get our permits renewed. The president cannot say we are all criminals.”

The crimes of Mara Salvatrucha have become the perfect excuse for Trump to attack the immigrant community, to justify deportations and roundups, to cancel programs that benefit Central American immigrants, and even to negotiate the border wall he is so eager to put up.

Miguel Alas, El Salvador’s consul in Long Island, told the Americas Program that of all the requests for legal assistance that the consulate receives, only 5 percent are related to crimes committed by gang members or with gang activity. Most problems, he said, have to do with intra-family violence and driving under the influence of alcohol.

Local police in Long Island’s Suffolk County say MS members are responsible for 19 murders committed between 2013 and 2016. Meanwhile, the authorities are still looking for a single serial killer who murdered 10 women in the same area.

Victims of violence attributed to MS were mostly young Latinos recently arrived in the United States, and the crimes occurred in Latino, rather than white, neighborhoods. That fact isn’t mentioned in the president’s speeches.

“In this anti-immigrant atmosphere, it’s very easy to attack undocumented immigrants with anti-crime rhetoric,” said Alex Sánchez, director of Homies Unidos, an organization that helps at-risk young people in Los Angeles, California. “After the failure of the zero-tolerance campaigns, and a truce that reduced homicides in El Salvador, the United States decided to name the street gang an international criminal organization. The Trump administration has raised the gang’s profile to historic levels by using the rhetoric that they are all immigrant criminals.”

The gang is one more excuse that Trump uses for refusing to resolve the situation of some 100,000 Dreamers and another 300,000 TPS beneficiaries, programs he canceled in September of 2017 and January of 2018, respectively. TPS granted legal protection and work permits to more than 200,000 Salvadorans. Now all of them are at risk of deportation.

In its most recent report on gangs and violence in El Salvador, the International Crisis Group shows how over the last 15 years, Salvadoran governments have promoted mano dura, or “iron fist” policies as a popular electoral campaign strategy rather than as a real solution to the problem of violence in that country.

“As violence soared after 2014 following the disintegration of a truce with the gangs, extreme measures of imprisonment and police raids have once again become the government’s predominant methods to choke the gangs. Allegations of police brutality and extrajudicial executions have multiplied,” reads the report.

The U.S. president’s anti-immigrant stance and his MS-based fear-mongering have also been used by other Republicans. One who caused special indignation was Jack Martins, who was running last fall for the top local post in New York State’s Nassau County.

The U.S. president’s anti-immigrant stance and his MS-based fear-mongering have also been used by other Republicans. One who caused special indignation was Jack Martins, who was running last fall for the top local post in New York State’s Nassau County.

County residents revealed that Martins sent posters to their homes with photographs of non-immigrant gang members imprisoned in El Salvador that accused his opponent, Democrat Laura Curran, of supporting MS and “illegal immigrants.”

“MS has become a profitable product for Trump,” said Omar Henríquez, of the National TPS Alliance in New York. “Here (in the United States) some people now believe that all Salvadoran young people are gang members. The young people are persecuted in this country by both the MS and the authorities. Many of them who were able to reunite with their families in this country fled here because they were being persecuted in their own countries.”

MS–Born in the USA

In the 1980s, thousands of Salvadorans left for the United States, fleeing a civil war in which the Reagan administration was supporting the Salvadoran army and extreme rightwing groups with funds and advisers. Salvadoran refugee families arriving in the United Sates settled in the south of Los Angeles, in areas that had been dominated by Mexican gangs.

As still happens, the young, mostly adolescent Salvadorans who came to the United States were harassed and attacked by the existing gangs that already had their territories carved out. To defend themselves, the Salvadorans decided to form their own group — the Mara Salvatrucha.

“When a lot of us arrived in the United States because of the war, we found ourselves needing to unite as a group, because they were attacking us, beating us, for no reason,” said Jonathan, a former Salvadoran gang member who lived much of his life as a member of Barrio 18 in New York. “That was the reason at the time. We were defending ourselves from the other ethnic groups already established in the streets.”

For the Salvadorans, the word “mara” means a group of young people, and “Salvatrucha” is a way of referring to somebody from El Salvador. With time, other young people from Guatemala and Honduras who were also abused by gang members joined up.

The gang gradually moved on from personal defense to violent crime, and also became involved with drug trafficking. When the civil war ended in El Salvador, the administration of then-president George H.W. Bush deported hundreds of Salvadorans who had committed crimes, among them members of MS.

“Some of the gang members began to get involved with drug sales, associating with other groups that already had a well-defined criminal organization, and along with that they began fighting with other gangs for territorial control,” said Jonathan. “That’s when some of them started to go down. They were arrested, and the ones that didn’t have papers were deported.”

El Salvador’s post-war atmosphere, with no plans in place for reinsertion programs for ex-combatants, provided an ideal climate for deportees with gang experience to start and expand local gangs while also maintaining connections with gang members who stayed in the United States.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, MS members forged an alliance with the Mexican Mafia, adopting the name MS-13. (The letter “M” is the thirteenth in the alphabet, and thus paid tribute to the role of the Mexican Mafia.) Some of the previously deported gang members returned illegally to the United States, while others stayed in Central America, expanding the brand.

“Things began to change because a lot of the gang members saw a way to make easy money, and that continues today,” said Jonathan, the retired Barrio 18 member. “When some of them allied themselves with other groups, they did it for money, for reputation, for drugs. And now the younger members do it for the same reasons — the easy money, the drugs. But a lot of us joined at first because the gang gave us status, to get people to respect us.”

In the United States and in El Salvador, gang members recruited by harassing and even coercing young people to join the gang, and began to extend alliances with the drug trade. In every region, the MS forms “cliques” to operate in sectors, with these sub-groups generally maintaining communication with each other.

“The cliques would decide on their own what to do,” Alex Sánchez, of Homies Unidos, said. “Some members got into the drug cartels, but not in the name of the gang. There have been groups within the gang that got involved in organized crime, but they don’t represent the gang. Today the younger ones get into the gang because life to them doesn’t matter, because they feel threatened by the violence and forced to join.”

The last four Salvadoran governments decided to confront the gang problem with repression. That, along with the lack of opportunities and the absence of violence-prevention programs, turned out to be the formula for gangs to grow and expand, making them a major problem not just for El Salvador but for Honduras and Guatemala as well.

“After 15 years of failed security policies, the government of El Salvador and criminal gangs are deadlocked in an open confrontation,” reads the International Crisis Group report, which goes on to note, “Born in the wake of U.S. deportation policies in the late 90s, gang violence in El Salvador has developed into a [Salvadoran] national security problem that accounts for the country’s sky-high murder rate.” The report also states, “The combination of iron fist policies and the U.S. administration’s approach to migration could worsen El Salvador’s already critical security situation.”

MS not the only gang in the U.S.

Trump also forgot to mention in his speeches that Mara Salvatrucha is not the only gang in the United States. According to FBI data, there are at least three street gangs bigger than MS, both in terms of membership and crimes committed.

MS has about 10,000 members in the United States, while Barrio 18 has 33,000 the Crips have 25,000 members, and the Bloods, made up mostly of African Americans, has between 20,000 and 25,000 members nationwide.

The MS is not the only violent group in the country, what’s happening is that since the president has been using it, the name is all over the place–in the news, in politics…”, said Jonathan. “Because it’s all about being against immigrants.”

The Mexican Mafia still appears on the FBI’s list of dangerous gangs, along with its affiliated gang known as Los Sureños, with some 30,000 members operating mainly in California, Arizona, Texas and Florida. Recently added to the list are Los Aztecas, which according to authorities engages in arms trafficking between the U.S. and Mexico, according to the FBI report.

Authorities and civilian activists in some Virginia counties and in Long Island, where the majority of MS members and MS crimes are concentrated, do not consider this gang to be a national security problem, but rather an issue calling for prevention strategies and attention to young people at the local level.

“The gang issue is a local problem, a problem that demands that Latino communities, parents, schools and the police itself be involved in prevention with young people.” aid Aby Lino, of Latino Justice and Boys to Men, civil organizations that work in the communities and schools of Long Island. “The problem of gangs is not a matter of national security, it is something local that we must respond with programs of attention to young people and prevention of violence.”

“What President Trump has done is assign to MS a power and notoriety that it doesn’t really have,” Jonathan said. “MS can’t expand or grow outside Long Island because besides having the government and police as enemies, it also has other gangs. Nobody wants MS and the gangs in the United States.”

Criminalizing minors and victims

The use of the MS as a tool just for attacking Dreamers, TPS beneficiaries and Central American immigrants also extends to refugees. Trump has connected this organization with unaccompanied minors, children and young adults who came to the United States in the last seven years fleeing the rampant violence in the Northern Triangle.

The use of the MS as a tool just for attacking Dreamers, TPS beneficiaries and Central American immigrants also extends to refugees. Trump has connected this organization with unaccompanied minors, children and young adults who came to the United States in the last seven years fleeing the rampant violence in the Northern Triangle.

Trump abruptly canceled the Unaccompanied Minors program, created by the Obama administration in 2014 to guarantee the rights of migrant boys and girls under 21 by permitting asylum applications to be filed in the home country, in August of last year. It had allowed legal immigrants to seek refuge for their children who were vulnerable to violence in their home country of El Salvador, Guatemala or Honduras.

“These are young people seeking refuge from persecution by the Maras and from police brutality,” said Sanchez. “The same mistakes of the past are being made. We as a community must recognize that these unaccompanied minors are arriving traumatized by violence.”

The decision to initiate this program was taken after the Obama administration recognized the existence of a new migration crisis in 2014 with the detention at the border of more than 65,000 minors traveling alone from their countries to seek asylum.

“Legally this was the protection provided to these children under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, so it excluded Mexican children,” said Chacón, the Alianza Americas director. “Now Trump is strengthening the attack on these kids, not to eliminate the Trafficking Victims Protection Act but instead to exclude Central American kids from it, using the excuse that they are gang members.”

The real face of the immigrants

Trump’s discourse, his use of the MS rhetoric against immigrants in general, and the cancellation of programs such as DACA and TPS, have forced the affected immigrants to break their silence. Activists and the immigrants themselves began a campaign last year to “show the Senate the true face of immigrants.”

“We began by asking why immigrants were being attacked so much, why so much aggression against Salvadorans . . . and from there we went to work to show senators their true face, and to explain the support we’ve given to the Central American immigrants in this country,” said Cecilia Martínez, coordinator of the National TPS Alliance for Long Island.

“A lot of people didn’t know who the Dreamers were, who the tepesianos (TPS beneficiaries) were. Now they know that we immigrants are not criminals, we’re not gang members, we’re human beings who have contributed to the economy and development of the United States with our taxes, our work, and our sweat.”

Since August of last year, this group of immigrants, mostly Salvadoran, along with other groups of activists, have taken on the task of organizing lobbying sessions in various senators’ Washington D.C. offices to ask for help in counteracting the negative image of Latino immigrants that Trump has been trying to create.

As of February 2018, 120 meetings have taken place to provide information to local and federal politicians. Martínez says that the group’s goal is for the senators to understand the important role that immigrants play in the United States, and then to promote reform that will allow them to obtain permanent residency that they deserve by right.

“All this anti-immigrant discourse and fear-mongering is creating the perfect framework for persecution against Latinos, and even the killing of Latinos by police,” said Chacón. “When we have an attorney general like (Jeff) Sessions who comes to Long Island to speak about gangs, advising the president in his attacks on Latinos, we are heading toward a cycle of violence. In about five years we’ll see some very negative results.”

Many already recognize the importance of employment for the immigrants and are looking to help the cause of worker protection in case of raids or persecution. In Long Island, close to 27 small businesses are working to educate their employees about their rights. Employee organizations from different sectors known as Sanctuary Unions organize “information days” for their co-workers to prepare them for possible ICE raids.

Martinez said that besides the lobbying of lawmakers, her organization also carries out information days in the Salvadoran Consulate, not just for her compatriots, but also for those from Honduras and Haiti who have been affected by the TPS cancellation.

“We are organizing more of these information days,” she said. “We work together with other groups like the Sanctuary Unions to bring the information to all who need it. At this point, the most important thing is to be informed.”

Immigrants protected by TPS say they will continue to counter President Trump’s rhetoric designed to damage their image, and that they won’t rest until the Senate starts looking for a way to grant them permanent residence.

Immigrants protected by TPS say they will continue to counter President Trump’s rhetoric designed to damage their image, and that they won’t rest until the Senate starts looking for a way to grant them permanent residence.

As for the Dreamers, Trump gave the Senate until March 5 to come up with a plan to resolve the situation of those who had been protected by the DACA program, a deadline that was de facto extended by court injunctions. Proposals so far have not gotten anywhere because the president insists on tying the Dreamers issue to funds for building a wall along the southern border with Mexico and increasing the number of border agents.

Translation by Kelly Arthur Garrett