By Ariela Ruiz Caro

The measures taken by President Donald Trump during his two months in office do not point to a path of prosperity and growth, as he announced during his campaign, but rather one of turbulence, chaos and uncertainty in the geopolitical and economic spheres. The downwardly revised economic growth prospect, the decline in consumer confidence indices, the contraction of investments and, in the second week of March, in the dramatic fall of Wall Street, which dragged down stock markets worldwide all reflect a critical situation. TESLA, the company of its star advisor, Elon Musk–the U.S. bearer of the Milei chainsaw for slashing public programs–has lost 40% of its value since Trump took office on January 20.

On Mar. 19 the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) concluded the second monetary policy meeting of 2025 and held interest rates between 4.25 and 5%. This is the second consecutive time that they have decided to keep them unchanged this year. The decision to keep rates stable comes in a scenario in which officials raised the average estimate of so-called core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, at the end of this year, from 2.5% to 2.8%. Similarly, the economic growth forecast for 2025 was reduced from 2.1% to 1.7%.

Trump’s trade war against his neighbors in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), is already slowing economic growth. Trump himself negotiated the USMCA before turning on closest allies, and his former strategic ally, the European Union, which he claims, either out of total ignorance or arrogance, was created to “bother” the United States.

The barrage of tariffs has also been imposed on China and Latin American countries including Brazil and Argentina. Trump has announced that he will impose tariffs on automobiles, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, wood and agricultural products. Even tariffs on copper are being investigated. Only someone as out of touch as Javier Milei could think that Argentina, in the current situation, could sign a Free Trade Agreement with the United States.

The field of international trade has turned into a battleground. Trump acknowledged that his tariff assault may cause some short-term economic pain for U.S. consumers. In an interview on Fox News on the eve of Black Monday when the stock markets plummeted, he stated that the economy is going through a “transition” phase. And he did not rule out a recession. “I hate to predict things like that […] There will be disruptions, but we are comfortable with that.”

President Trump’s approval rating has seen a significant decline. However, other polls indicate even higher disapproval ratings for his presidency in various aspects. According to NBC News, the number of respondents who disapprove of his administration surpasses those who approve by four percentage points. For Economist/YouGov, the disapproval margin stands at 51%, compared to 46% approval. For Morning Consult, in a survey conducted on March 14, disapproval registered 50%, surpassing the 48% of respondents who maintain a positive image. Other polls show him maintaining a slight majority: According to a Rasmussen Reports poll, 51% of voters still approve of Trump’s performance compared to 48% who disapprove, but the rapid decline in his image is striking, given that the difference between the two parameters has dropped from ten to just three points in less than 15 days. The outlier, RMG Research/Napolitan News Service, shows 54% approve, while 44% disapprove of his management.

The cure is worse than the disease

On Mar. 12, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from around the world, without exception. With these measures, he is recklessly attempting to revive an industrial base that moved to other countries at the height of globalization. Trying to reverse this complex framework through tariffs is a senseless move that will only have negative consequences.

Not all affected countries -Canada, Mexico, the European Union, China, Brazil and Argentina, India, China, among others- have implemented retaliatory countermeasures. Latin American nations, for now, have refrained from doing so. Trump threatened Canada with doubling those tariffs to 50%, but backed down when the governor of the Canadian province of Ontario withdrew plans to impose a surcharge on the electricity his province sends to the United States. Canada, as the U.S.’s main supplier of steel and aluminum, receives the brunt of the tariffs. Adding to the tension are Trump’s repeated remarks about his desire to incorporate Canada as the 51st state of the U.S. In response, several countries, particularly Canada, have seen the emergence of organized boycotts against purchasing U.S. products.

Tariffs will raise costs for certain U.S. industries that heavily rely on steel or other affected products. Those who defend the president’s plan argue that, ultimately, the tariffs will encourage more manufacturing in the United States. In that case, businesses will have to bear the higher prices, which will likely lead to decreased demand and, consequently, lower production—impacting jobs as well. This is without considering any retaliatory measures imposed by affected countries. The notion of reviving a lost industry is nothing more than a fantasy.

Trump presents the imposition of these tariffs as necessary to rebalance a global trade system that has been “ripping off” the nation as seen in growing U.S. trade deficits with the world’s major economies. What Trump fails to mention is that the U.S. dollar serves as a reserve and circulating currency, the foundation of its global hegemony. The surplus of dollars from the trade surpluses that the European Union, China, Japan, Mexico and many other countries maintain with the United States flow back into the country—whether through the purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds, investments in real estate, mutual funds, or stock markets. In other words, a significant part of these trade surpluses return to the North to finance its budget or investments. The huge defense expenditure, among others, could not be financed without this global capital flowing into the United States.

Chaos and uncertainty

The Atlanta Federal Reserve model predicts that U.S. GDP will shrink by 2.8% in the first quarter of this year. The new forecast differs significantly from just a month ago when it estimated nearly 4% growth for the same period. The decline could be explained by the record trade deficit of $153 billion in January. The 25.6% increase in the trade deficit since December was probably due to companies rushing imports before Trump declared his tariff war. Meanwhile, the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) recorded its sharpest monthly drop since 2021 in January.

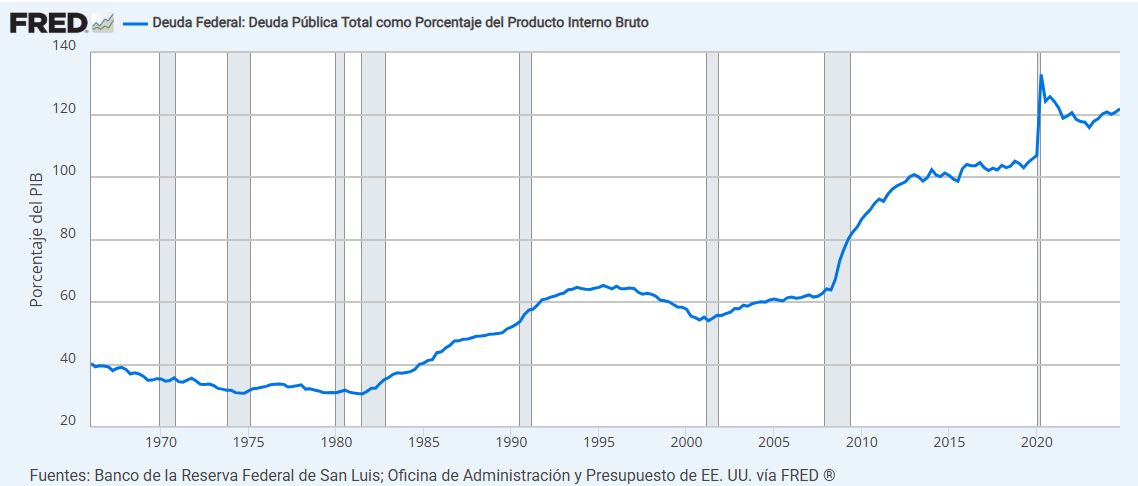

The United States is in a spiral of debt crisis that is accelerating rapidly. Its debt-to-GDP ratio (120%) is expanding faster than that of any other developed nation and has become a threat to global stability. This year, the country is set to pay nearly $10 trillion in interest alone—an amount exceeding its annual defense spending. Its fiscal deficit stands at approximately 7% of GDP. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that the country’s budget deficit and its debt pose “a growing risk” to the global economy. According to Elon Musk, the director of the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), the U.S. is on a path to bankruptcy. Even Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell stated in July of last year that the country’s public finances are “unsustainable

President Trump is aware of the dollar’s vulnerability, as are the holders of U.S. debt securities—such as Japan, China, India, and Saudi Arabia—who are offloading them and replacing them, among other assets, with gold. This week, gold neared $3,000 per ounce, a phenomenon never before seen in history.

Nothing lasts forever

As the Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis points out, to boost exports, bring jobs back home and reduce the trade deficit as Trump hopes to do, a depreciated dollar is needed. However, to maintain its global hegemony, the U.S. also requires a strong dollar. How can both be achieved at the same time?

Varoufakis posits that the noise and uncertainty created by rising tariffs tend to strengthen the dollar. This happens whenever there is a crisis, even when it is generated in the United States, as happened during the economic and financial crisis that erupted in 2008. Also, if the US government continues to cut taxes for large corporations and high-income sectors, this will attract large amounts of foreign capital to the United States, another factor in the appreciation of the dollar.

A third factor contributing to the dollar’s strength is its hegemonic role, which allows it to appreciate in all crisis scenarios. If Trump really wanted to reverse the trade deficit, he would have to undermine the dollar’s global dominance. Obviously, he wouldn’t want to go down in history as the president who ended the privileged status of his country’s currency.

Like some other economists, Varoufakis believes that Trump’s true goal in imposing high tariffs is to negotiate a deal with his main trading partners. The idea is to remove tariffs in exchange for an appreciation of their currencies in order to reduce the U.S. trade deficit through exchange rate adjustments.

This strategy specifically targets China, the main source of U.S. imports. The model would be similar to the Plaza Accord, signed with Japan in Ronald Reagan’s time in 1985, through which Japan accepted the appreciation of its currency. As a result, the U.S. narrowed its trade deficit with Japan without relying on tariffs. However, it is clear that China would not accept a currency appreciation on the terms the U.S. seeks to reduce its trade gap.

The question posed by the Greek economist is whether China will simply stand by and watch for four years or if, at some opportune moment, it will work within the BRICS framework to create a system similar to Bretton Woods, with the yuan as its central currency. This would involve establishing a fixed exchange rate between the yuan, the rupee, and other currencies of participating nations. Such an arrangement would spell the end of the dollar’s hegemony in the international monetary system. That is why Trump is threatening to impose 100% tariffs on the BRICS countries if they stop using the dollar in their commercial transactions.

If the dollar were to lose its hegemonic role and become just another currency, it would be extremely serious for the United States, especially in a scenario in which the country has been deindustrialized as a result of the neoliberal globalization process that they themselves promoted, with a weak financial structure with high levels of indebtedness and fiscal deficit. In this context, the trade war and Trump’s annexationist ambitions are tactics rooted in the process of his own debacle, which will have serious consequences for the international economy.