“My papa settled here in 1944,” Pablo Sarmiento says in a serene voice and gentle manner, as he looks at the ruins of his home that was torn down by a multinational’s bulldozers. They arrived on May 24, without prior notice, judicial orders or signed authorization. They encircled the houses with wire fences to delineate the property of the new “investor.” Pablo looks out at the barren plain at the foothills of the Andes, where just 80 to 100 millimeters of rain fall every year; only the sounds of the trucks along Ruta 40 interrupt the silence.[1]

“My papa settled here in 1944,” Pablo Sarmiento says in a serene voice and gentle manner, as he looks at the ruins of his home that was torn down by a multinational’s bulldozers. They arrived on May 24, without prior notice, judicial orders or signed authorization. They encircled the houses with wire fences to delineate the property of the new “investor.” Pablo looks out at the barren plain at the foothills of the Andes, where just 80 to 100 millimeters of rain fall every year; only the sounds of the trucks along Ruta 40 interrupt the silence.[1]

Pablo is one of the seven children of José Celestino Sarmiento who continued to work as a shepherd, just as his father did. He used to have some 200 animals on these dry open lands, where there is no water and pasture is sparse, where they built homes, feed sheds, and drilled 174 meters down to find pools of water for their animals to drink. Since Pablo and his sons wanted to remain on the land that their family has occupied for nearly 70 years, they tried to file a complaint, which the police refused to accept. Meanwhile, they found out that the company wanted them tried as usurpers.” [2]

The shepherds are small farmers who practice nomadic ranching; they rotate their animals through several fields, depending on the availability of pasture and water. This kind of work forces them to move between different posts or “puestos” to care of their animals—goats and cows, at times hogs and poultry. “It takes me about 20 days to move my 200 animals because they’re all scattered,” Pablo explains.

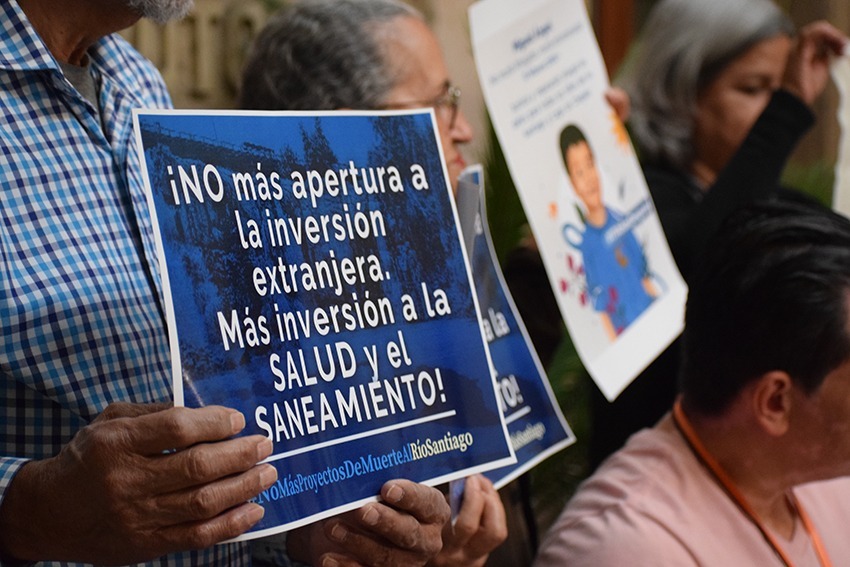

From the distant past, these open, public lands have been considered communal grazing lands because of their low productivity. “At times seven and eight months go by without rain, everything is dry, even the mesquite dries up. The fences began going up four years ago. They buy, fence off the land and plant olive trees.” Pablo explains that the new “proprietors” paid off people who engaged in dubious legal proceedings to justify possession of land that was never owned by anyone.

Doña Carmen is the name of a business belonging to the Spanish company Argenceres, located between the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, which has more than 38,000 hectares. On its website, the company describes the olive grove that now occupies more than 2,000 hectares: “Irrigation is automated with a pressurized, double-lateral drip fed by the wells themselves, which guaranties high-quality water and a modern sustainable harvest.” The company goes on to say that “due to its vast size, perfect climate and the quality of soil, Doña Carmen will lead Argenceres’s growth in the next few years.”[3]

As to the proprietors, the company itself recognizes their participation in land speculation. “The parent company of Argenceres is Inversora Portichol, an important Spanish business group that comprises diverse sectors such as real estate, building materials, fashion, biotechnology and genetic research.”[4]

Pablo and the other puesteros, as well as the landless campesinos of Mendoza, know that they face powerful enemies: agribusiness allied with local economic groups protected by the provincial government. Pablo belongs to the Unión de Trabajadores Rurales Sin Tierra (UST) [Landless Workers Union], which set up a tent to resist as long as may be necessary. Its nearest local is in Jocolí, 25 kilometers from the puesto attacked by the company.

The newspaper La Nación contacted the person in charge of the puestero program in Mendoza’s Department of Planning and Urban Development, Leonardo Miranda, who stated that the Sarmiento family had held possession of the land since 1944. “In the meantime, titles passed through many hands, but, in effect, the Sarmientos always had possession.”[5] Therefore, according to the state official, the family has the right to remain there.

Moreover, he says, the family figures in the registry of signs and brands, which authorizes it to sell its animals. They have been counted in various agricultural censuses and registered in the Registry of Puesteros. “Therefore there’s no way that they can make a case of usurpation,” says Miranda. Nevertheless, the law is no guarantee in a country and in a province in which all legislation is vulnerable to the interests of big business.

Production and Organization

Jocolí is a small village in the department of Lavalle, on the border of the province of San Juan. With red dirt streets and low houses, the entire region is dominated by the austerity caused by water scarcity. We arrive at a series of brick buildings where a large group receives us: Manuel, Carolina, Facundo, Lena, Marta, Gonzalo and several more emerge from the various places that comprise the regional office of the UST. After formal introductions, they begin to show us the installations.

In front, a room with computers for members of the movement and their families. To one side, another room with the community radio inaugurated less than a year ago. We walk and see a large nursery. That’s where seedlings for gardens and communal lands claimed by the movement come from. In the back is a bodega where grapes are pressed and “Campesino” wine is bottled. At one side is the fruit and vegetable processing plant, which produces tomato sauce, jams, and the wide variety of products that prove that resistance and production are both necessary and possible. In the center, the “Campesino School,” a space that they are proud of.

The movement is ten years old. It was born in December 2002, in the midst of demonstrations in front of the Lavalle municipal government. The demonstrations were called by collective organizations in the area to demand that farms abandoned in the wake of bankruptcy caused by the economic crisis be given to the unemployed for their subsistence. Instead, municipal officials gave the information they had received from the campesinos to big business, to facilitate new businesses in the area. “That’s when we learned that we couldn’t expect anything from the state,” said a member of the UST.

The organization now has 700 families. They are divided into five regional organizations and 30 base groups. With 200 families and seven base groups, Jocolí, for example, is perhaps the most important. “A base group is a group of families within a specific territory that has an identity and meets regularly to define tasks,” explains Facundo, an agronomist who came to live in this arid corner in the north of Mendoza.

In addition to being organized by regional territory, the movement has five program areas: production and distribution, education, health, communication, and territory. It has groups defined by gender and groups for children, with camping, music workshops, and games. Our discussion focused on production, which involves a horizontal chain that begins with the nursery and ends with the agricultural fairs and fair trade networks that reach the tables of consumers, whom UST members hope will become increasingly conscious of what they are consuming.

A group of four people is in charge of the nursery where they raise tomato seedlings, melons, watermelon, vegetables and flowers, Carolina explains. They buy seeds and grow them until they can be transplanted. At that point, there are several possibilities: They can be sold to members of the movement or given to a family in exchange for part of the family’s final production that is set aside for the movement. Mixed forms of exchange, combining payment with barter and various forms of cooperative arrangements, also take place.

“Let’s take the example of the productive chain of the tomato,” says Lena. “The seedlings go to the movement’s communal lands, where they are raised by some 20 families. But they also can be given to other regional organizations. Then the tomato arrives at the plant, there are seven compañeras who process it, as sauce or whole tomatoes. The same thing with jam. In addition, there is a mobile store that that brings products to the house.”

Forms of work overlap in an almost infinite variety of ways. Families with land at times share with other families in the movement. Other families combine working the land with working for wages as masons or other jobs. Families with vineyards bring grapes to the bodega and pay with wine, something that occurs with other products as well. “Campesino culture is very diverse as far as the means of exchange and cooperation are concerned. And that forms part of the movement.” In other cases, the movement contributes inputs such as gasoil. In return, part of the harvest goes to the movement.

The total amount produced is considerable. Some 30,000 bottles of tomato a year, in sauce or whole, wines, sweets, jams, honey, chickens, eggs, wholesome animal feed, pasture. Currently there are several sporadic sales a year; they are organizing a permanent campesino fair in Lavalle. “The agriculture we do is for local consumption, not for export,” says Lena. “In reality, we’re doing what a traditional campesino family that doesn’t use preservatives does.”

Campesino culture consists of harvesting in the spring and fall and saving for winter, when there is no production. That’s why a good part of the production is processed as preserves. In essence the movement functions as a sounding board for campesino culture, or at least the non-oppressive aspects of that culture, since it also fights against machismo and abusive attitudes.

Land, Water and Poverty

Manuel explains that one of the objectives of the UST is “the formation of country families, so that they can defend their lands. That’s why we conduct workshops to discuss legal issues to be able to confront evictions. Businessmen buy land with shepherds and people on it, and later they consider them usurpers. The shepherd has no papers, but inherited possession from grandparents who settled decades ago.”

More subtle is the way water, without which there can be no production, has been appropriated. “The process of appropriation of water consisted in diverting rivers to farms that belong to the oligarchy,” explains Manota. “Just 3 percent of territory in the province is irrigated; they are the richest lands because they diverted the rivers. The other 97 percent is known as ‘dry land,’ and is associated with the idea of ‘desert.’ There are no fincas, just fields. Of that 97 percent, more than half are campesinos farming communally.”

International capital is advancing over those fields. The price paid for land is ridiculous compared to the price paid in countries in the North. “A hectare bought legally is worth 10,000 pesos ($2,500), but they end up paying 500 and or just 100 pesos ($125 to $25) by forging titles. The conflict with the Spanish company involves speculative capital. Since they pay very little for land, they have a lot of money left over to invest. They’ve drilled illegal wells to water the olive trees, which leaves the rest without water,” he explains.

With current technology, they don’t have to buy land with water rights, which is always more expensive. Instead they can buy dry land that can be irrigated with very deep wells–up to 300 meters–and an enormous deployment of machinery. Manuel says that 60 percent of the farms in the zone are abandoned because of the effect of the crisis on the productive model; many producers went bankrupt. “They stop cultivating, but the water bills keep coming until they owe more than the farm is worth. That’s when all the maneuvering begins with law firms and intermediaries who forge property titles.”

Lena adds that many “investors” receive subsidies from the state without any environmental impact studies. A network of corruption, beginning in Buenos Aires, led to several titles being applied to the same land. “The limited resource, the one that is going to generate the value of land, is water. That’s why they appropriate it.” Corruption has allowed for the violation of one of the market’s most sacred laws: As demand for land increases, the price decreases.

There is a process by which ownership of land becomes concentrated, says Facundo. “A third of the population of Mendoza is rural, and 80 percent of that third has no land.” To survive, landless inhabitants of Jocolí work from Monday to Saturday, eight to 12 hours a day on far-off farms.

Encounter with dignity

Jacqueline works four hours a day in the nursery and receives a day’s wages. At times they buy boxes of tomatoes designated for family consumption, but there are other working arrangements that allow workers to take part of what they produce. Each base group is self-managed. Members choose which area they want to work in. They elect delegates to an assembly that take place every three months, and participate in biweekly regional meetings. The UST is part of Vía Campesina, and takes its inspiration from some of the principles of the MST (Landless People’s Movement) of Brazil.

“In 2002 an unprecedented encounter between campesino groups and academic agronomists occurred over the problematization of land and water,” says Manuel. In the School of Agronomy, members of the “Martin Fierro” student group developed relationships with campesinos. When they finished their studies, several agronomists decided to go live as campesinos in Lavalle. Year after year they were joined by lawyers, social workers and more agronomists. The union of both sides made possible the birth of the UST.

Facundo, 31 and Lena, 34, left the city and have been living in Jocolí for 10 years. They’ve formed families, had children, worked the land, and dedicated a lot of time to the UST. “I grew up in the country, so I don’t miss the city,” declares Facundo. “In addition to the opportunity to build a campesino organization, we had the opportunity to get beyond the whole notion of individualism through a collective economy.”

Agronomists committed to campesinos can no longer work in private firms. They have been expelled from institutions and decided to share their income from whatever jobs they may find to continue working full-time on the struggle for land. Says Facundo: “We work the land, we produce eggs, chicken, some goats, but that’s not enough. That’s why we’re created a communitarian economy among ourselves.”

“In these 10 years I learned to value the ties between people from the other side. There are many false necessities–wasting water, consumption. The relationships of solidarity and cooperation that in the city are restricted to the family circle, are more common here,” Lena explains. “The most important change among people is in their self-esteem, when they discover that they can do things without depending on a politician or a leader, above all the women.”

“In conflicts over land, women are in the front line, but when there’s a discussion the men are there,” Facundo interjects.

It’s almost dusk. Surrounded by a cloud of dust, we pass in front of a bright, green field of alfalfa.

The family growing that grows the alfalfa keeps part and gives the rest to the movement as compensation for renting the field. “We promote diverse systems of non-monetary exchange, such as barter, because it is a way of strengthening family ties. We also work together in collective work, with good results.”

The bodega and factory machinery, the silkscreen, three tractors, harvester, mower, and small machines are obtained with state subsidies and funds from international organizations. The challenge is to maintain relationships with powerful institutions, while maintaining their principles – lack of hierarchy, autonomy, equality in spite of differences–to build a new society.

Raúl Zibechi is an international analyst for Brecha of Montevideo, Uruguay, lecturer and researcher on social movements at the Multiversidad Franciscana de América Latina, and adviser to several social groups. He writes a monthly column for the Americas Program (www.americas.org).

Translated by Barbara Belejack

Resources

Argenceres (Spanish-Argentine company): www.argenceres.com

“Grito Cuyano,” UST newspaper, April 2010 and January 2011

MDZ Online (Mendoza digital daily newspaper): www.mdzol.com

Movimiento Nacional Campesino Indígena: www.mnci.org

Unión de Trabajadores Rurales Sin Tierra (UST): www.ust-mnci-blogspot.com

Raúl Zibechi, interview with members of the UST, Jocolí, June 4, 2011

[1] Ruta 40 is a 5,000 kilometer highway that unites southern Argentina with La Quiaca, on the Bolivian border , and which runs along the length of the Andes.

[2] Mendoza Online, May 31, 2011 in http://www.mdzol.com/mdz/nota/299412

[3] www.argenceres.com

[4] Argenceres and www.grupoportichol.com

[5] La Nación. June 11, 2011, in http:www.lanacion.com.ar/1380472-la-posesion-de-la-tierra-eje-de-un-conflicto-en-mendoza