Silent traumas grip a growing number of families in Mexico. Not knowing where a loved one is, relatives comb jails, hospitals, morgues and common graves. Digging into the earth, their shovels probe for bodies or remains–fragments of a human being who once warmed their lives. Unable to sleep or lead normal lives, mothers, fathers and children wait for that phone call or text message that provides a definitive answer or at least a real lead.

Silent traumas grip a growing number of families in Mexico. Not knowing where a loved one is, relatives comb jails, hospitals, morgues and common graves. Digging into the earth, their shovels probe for bodies or remains–fragments of a human being who once warmed their lives. Unable to sleep or lead normal lives, mothers, fathers and children wait for that phone call or text message that provides a definitive answer or at least a real lead.

Maria de Jesus Marquez knows all this too well. In October 2012, an armed commando with the appearance of state ministerial police burst into her home and made off with her son and another young man, the mother told a recent conference on forced disappearance in Ciudad Juarez. “Since then, my journey has been difficult,” Marquez said. “There are nights we don’t sleep, from insomnia, stress… I’m asthmatic from before and it acts up.”

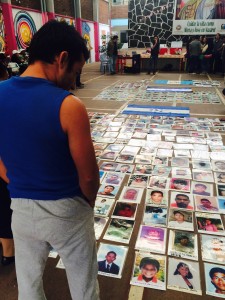

Marquez shared her story at the event “I Will Look for You”, Sept. 26-27, hosted by the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juarez and co-sponsored by other local universities and human rights organizations. The conference brought together activists, victims’ relatives, government officials, international representatives and academics.

Held on the second anniversary of the forced disappearance of the 43 Aytozinapa college students in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, the gathering analyzed different forms of forced disappearance in Mexico, explored the growing role of families and civil society organizations in undertaking physical searches for the disappeared, debated how to end forced disappearances, and discussed ways of procuring justice.

Alan Garcia, representative of the United Nations Officer of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, outlined the modern history of forced disappearance in Mexico. He traced it back to the Dirty War of the 1960s to early 1980s, when the army and Interior Ministry unleashed fierce repression against suspected leftist guerillas and other dissidents.

According to the Guerrero daily El Sur, two of the missing Ayotzinapa students, Cutberto Ortiz Ramos and Bernardo Flores Alcaraz, have seven relatives between them who were disappeared by the government during the Dirty War.

Nowadays, forced disappearance is “more complex,” Garcia said, with a plurality of actors from all branches of government, a diversity of motives and a wide range of victims that includes not only male political activists, but also migrants, children and women. He called forced disappearance a “critical problem” damaging families, hurting society as a whole and undermining the credibility of the State.

“Pacts of silence” among the parties responsible for forced disappearance are central to suppressing the truth in Mexico and Latin America, said Carlos Beristain, former member of the Interdisciplinary Group of International Experts (GIEI), an independent panel appointed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to probe the Ayotzinapa atrocity. “A strategy has to break the pacts of silence,”Beristain said.

Dr. Carolina Robledo, researcher and instructor with Mexico City’s Center for Research and Higher Education in Social Anthropology, called the use of clandestine burial grounds a “characteristic of war” that function as “mechanisms of elimination and terror, a way of forgetting and preventing collective and personal mourning.”

Exhumations of secret graves jeopardize pacts of silence and provide important clues to a crime, Robledo said. “Each time we exhume a grave it should tell us what is happening, how it happened and who are the actors involved,” she said. “It’s not only about taking out bodies… I’ve talked to forensic anthropology friends and they say the bones speak, and in fact, they do speak.”

Coahuila and Chihuahua, Highest Rates of Disappearance

Two northern Mexican border states, Coahuila and Chihuahua, illustrate the enormity of forced disappearance and the obstacles in identifying victims and achieving justice.

Michael Chamberlin, a veteran Mexican human rights advocate who works with Forces United for Our Disappeared in Mexico (FUNDEM) and the Fray Juan de Larios Center in Coahuila, a project promoted by Bishop Raul Vera, told the conference that the Coahuila state prosecutor’s office has 1,791 complaints of disappearance on file. Considering the number an undercount, Chamberlin added that 458 bodies are awaiting identification, not counting the many deteriorated remains in government custody.

“Many of these are surely migrants–the bodies in the common graves–because migrants often pass through Coahuila,” Chamberlin said.

Coahuila’s disappeared began to get serious notice during the period of 2009-2011, when relatives banded together and a United Nations working group on forced disappearance visited and issued recommendations, he said. The years in question coincided with a sharp uptick in narco-related violence in Coahuila, including the 2011 Allende Massacre, when an estimated 300 people were abducted and presumably executed by gunmen linked to police and the Zetas cartel.

Family members have since established a working relationship with the Coahuila state government, collaborating in reviewing files, forensic processing and information to help identify victims, according to Chamberlin. Casting a broader net to cover the possible pool of victims, the group is attempting to secure an agreement with Mexico’s National Electoral Institute so the data can be cross-checked on as many as 90 million people, he said.

At first, locating the disappeared in Coahuila loomed as a herculean challenge. “The State wasn’t institutionally prepared to confront a problem like this,” Chamberlin recalled. “There were no (storage) warehouses, evidence was lost…there was no processing of clothing, or identifications that could tell…”

Though the government-family collaboration has made some progress, relatives view the passage of relevant legislation as critical since a new state government will take office after elections next year, Chamberlin added.

Chihuahua is another state hit hard by forced disappearance. Gabino Gomez, longtime rural leader and a representative of the Chihuahua City-based Women’s Human Rights Center, described the drama of Cuauhtemoc, a medium-sized city that sits on the narco routes connecting to the Sierra Madres.

Of 1,799 people officially registered as disappeared in Chihuahua, 377 are from Cuauhtemoc, a figure that proportionally constitutes the “largest rate of disappearance in the country,” according to Gomez. A former prosecutor told activists that the real number of disappeared in Cuauhtemoc stood at 900, he said. Gomez put Cuauhtemoc’s disappeared in two main groups: males aged 16-30 and women who could be victims of sex trafficking.

In contrast to other crimes like kidnapping and murder, forced disappearance got scant attention until movements such as the 2011 national Caravan for Peace and Justice initiated by poet Javier Sicilia and the 2014 Ayotzinapa protests brought the issue to the fore, he added.

In Chihuahua, relatives probing the disappearance of a loved one confront run-rounds, intimidation and retaliation. Gerardo Baca Portillo, who blames soldiers for disappearing his son and a friend in 2009, said military officials have blocked any possibility of a meeting with him and he initially received no response from the Office of the Federal Attorney General (PGR).

“I’ve had telephoned threats, (saying) if a friend of my son continues to testify, ‘you’ll be dead’,” Baca said.

His son’s case finally received official attention after getting international press coverage and support from the Paso del Norte Human Rights Center and Mexican senators, Baca added.

On October 4, newly inaugurated Chihuahua Governor Javier Corral announced he will establish a special prosecutorial division for grave human rights violations. Gabino Gomez and other human rights activists presented the proposal to Corral during his campaign. The governor also said he’d sign an agreement with the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team for identifying remains found in clandestine graves and processing genetic material, and denounced torture in obtaining confessions.

“We are going to restore the tranquility of society. We are going to address the problem of forced displacement of communities in the mountains, and we are going to combat the phenomenon of the disappearance of persons,” Corral was quoted in the Ciudad Juarez media outlet Arrobajuarez.com.

The same day as Corral’s inauguration, the Chihuahua press reported that Javier Benavides would assume charge of the Chihuahua state police. An old militant of Corral’s National Action Party, Benavides commanded the state police and then served as chief of public safety in Ciudad Juarez during 1992-2000. During this period, the border city was engulfed in the first wave of femicides, intensified narco-executions and more than 200 forced disappearances of women and men, many of them blamed on state and municipal police.

In 2000, Benavides filed defamation charges against two local journalists. Both were briefly jailed before the police official dropped legal action. Ironically, one of the journalists, Antonio Pinedo, is now Governor Corral’s communications director. As new controversy swirled around Benavides, Corral insisted that the appointment would be temporary.

Forced Disappearance on the National Political Agenda

Many human rights advocates consider the Mexican government’s national estimate of nearly 28,000 disappeared people too low, due to multi-agency shortcomings in the way reports are processed, the lack of a centralized national data base and the fact that many relatives of missing persons are simply afraid to file a report out of fear of retaliation.

“We are confronting a problem of national magnitude,” said Senator Angelica Pena, president of the Mexican Senate’s human rights commission and the sponsor of pending legislation on forced disappearance. “Is the problem in the north or in Guerrero (state)? No, there isn’t a state in the country that doesn’t have a register of the disappeared.”

Preventing, sanctioning and resolving forced disappearance ranks high on the agenda of Mexican human rights activists. At the Juarez forum, the university’s Hector Padilla proposed the creation of a Chihuahua truth commission. Previous commissions have probed similar atrocities in Guatemala, El Salvador and the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca, among other places. Dr. Carolina Robledo spoke about an activist-inspired rapid response group in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, dedicated to searching and filing legal orders within hours of a report of a disappearance. The Fray Juan de Larios Center and the Mexico City-based Foundation for Justice reported on their ongoing work with partners in Central America and the United States focused on finding the disappeared.

“There is a big population in the U.S. looking for disappeared persons in Mexico and Central America,” Foundation for Justice Executive Director Ana Lorena Delgadillo said.

Father Oscar Enriquez, Paso del Norte Human Rights Center director, challenged academics to get involved, sketching five areas that require research and analysis including women, secular society, refugees and migrants, territorial control, and the failed State.

“Victims have to be at the center of the entire society,” Enriquez said. Accordingly, Maria de Jesus Marquez recounted how meeting a priest who put her in contact with the Paso del Norte Human Rights Center helped end her isolation and get legal and psychological support. Joining a network of relatives of disappeared persons helped Marquez cope with deep pain, she said. “I felt alone at first, because I didn’t know what to do or how to do it,” the mother said.

Skepticism greeted a presentation by Laura Adriana Vargas, general director general of the PGR’s specialized search unit for disappeared persons. Vargas laid out a chronology of federal intervention beginning with the Fox administration’s special prosecutorial division that probed the Dirty War in the early 2000s, an effort that ultimately failed to give definitive answers about the fate of disappeared persons or hold former officials accountable.

She cited two landmark decisions rendered by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2009 that she said shape Mexican policy. The cases is the 1974 disappearance of Rosendo Radilla during counterinsurgency operations in Guerrero, and the other the 2001 discovery of eight murdered young women and girls at a place in Ciudad Juarez known as the Cotton Field (Campo Algodonero).

“All our authorities are obliged not only to respect them but apply them as well,” Vargas said of the court sentences.

In both Radilla and the Cotton Field cases, the Inter-American Court ordered reparations, justice reforms and the punishment of guilty officials after finding the Mexican State responsible for human rights violations. Yet both cases remain mired in impunity.

Considerable discussion ensued over the anticipated passage of a national law on forced disappearance this fall.

“A law doesn’t transform reality by itself. It’s a tool to search for the truth about our disappeared people,” said Humberto Guerrero, a human rights attorney who worked on the Radilla case and now serves as coordinator for the Mexican NGO Fundar.

According to Guerrero, five laws have been proposed in the Senate, three authored by lawmakers including Senator Pena, a measure proposed by President Pena Nieto and one drafted by civil society organizations. Guerrero and Senator Pena said the main differences in the proposed laws have to do with the respective role of state and federal law enforcement agencies, the bureaucratic structure that will emerge to oversee the process and most importantly, the participation of family members in investigations and searches.

Guerrero contended the President’s proposed law would preserve the status quo by reserving the main responsibility for investigations to state level institutions, which he described as infiltrated and corrupted by organized crime.

“For better or worse, the (federal government) has to assume a leadership role so the investigations happen at the state level,” Guerrero said. Families, he said, favor a decentralized agency on disappearances connected to the PGR but with autonomy, and a provision for a national search commission that would have the legal authority to conduct searches if other officials do not.

Senator Pena said federal-state coordination in investigations already exists, but that a new law should expand cooperation to include searches. Pena added that a national forensic data base should come from new legislation.

The U.N.’s Alan Garcia said the international body is highly supportive of the legislative push, but cautioned that any new law should have a budget assigned to it by mid-November when lawmakers finalize spending numbers for next year. Senator Pena said she expected a law to be approved later in October.

Meanwhile, the Movement for Our Disappeared in Mexico, a national network of more than 70 human rights organizations and relatives’ associations, is mounting a national campaign of eight demands to insure that searches are prioritized and families have a strong voice in a new law.

Called “Sinlasfamiliasno,” or “No Law without the Families,” the campaign plans a petition drive directed at lawmakers between October 15 and 22.

The Long Shadow of Ayotzinapa

As the debate over a national law against forced disappearance reaches a possible climax, the unsolved case of the 43 Ayotzinapa college students abducted by security forces in September 2014 looms over Mexico. It has come to be viewed as a litmus test for political will in upholding human rights and ending impunity.

Spanish psychologist and doctor Carlos Beristain, who investigated Ayotzinapa as a member of the GIEI before the Mexican government denied a family demand to continue the group’s investigation, recounted the experience of the international experts.

Right off the bat, Beristain, who has long international experience in conflict zones, said he was very surprised by comments of victim’s relatives pleading with the GIEI not to accept money and “sell-out.” In Iguala, the scene of the crime, the GIEI found possible witnesses afraid to talk, intimidated “in a context of terror where they could be next,” he said.

Beristain ran down a litany of problems in the Mexican government’s official investigation, ranging from scattering the cases of suspects in tribunals across the country, to concealing or failing to collect evidence. He stressed that such irregularities are not unique to Ayotzinapa, but “continue presenting themselves in criminal investigations and human rights in Mexico.”

Despite the obstacles, the GIEI made progress, documenting the presence and/or involvement of the Mexican army and Federal Police near the attacks against the students and soccer players from the Avispones team, according to Beristain.

The international human rights investigator, who has also probed atrocities in other Latin American nations, discounted a government hypothesis that the students were confused with members of Los Rojos criminal gang, saying all the pertinent security forces knew the Ayotzinapa students were headed to Iguala two hours ahead of time.

A lead that needs to be seriously examined, Beristain insisted, was a fifth bus initially used by the Ayotzinapa students that was not attacked by police like the others. Instead federal officials hid the existence of this bus from the public. Despite the barriers, Beristain said the experience showed a genuine investigation could be done.

Although the Peña Nieto administration denied an extension of the GIEI investigation, it did agree to an IACHR request to monitor the experts’ report and see if its recommendations are being followed. Beristain said the follow-up will not be an investigation like the GIEI did, but focus instead on the government’s response to the recommendations.

He asserted that so far “we haven’t seen any positive steps” from the government, adding that the transfer of former PGR official Tomas Zeron, who is accused of mishandling evidence during the Ayotzinapa investigation, to an important position in the President’s National Security Commission is “a bad signal.”

More than two years after the so-called Night of Iguala, the students remain disappeared with no credible explanation of their fates. Almost to the date of the second anniversary, two Ayotzinapa students, Jonathan Morales Hernandez and Filemon Tacuba Castro, were reported murdered along with another person October 5 in the state capital of Chilpancingo.

For Beristain, Ayotzinapa represents an opportunity for transformation or regression in Mexico.

“The (GIEI) recommendations have to be taken into account or forced disappearance will continue in Mexico for many years, from generation to generation” he said. “These cases are going to perpetuate.”

Resources:

Spanish language resources: Sin Las Familias campaign: www.Sinlasfamiliasno.org

Paso del Norte Human Rights Center, Ciudad Juarez: https://es-la.facebook.com/Centro-de-Derechos-Humanos-Paso-del-Norte-AC-309494775768842/

Fray Juan de Larios Center, Coahuila: http://www.derechoadefenderderechos.com/pbi-mexico-fray-juan-larios.html

FUNDAR , Mexico City: www.fundar.org.mx

Foundation for Justice, Mexico City: www.fundacionjusticia.org

Women’s Human Rights Center, Chihuahua City: http://cedehm.blogspot.com/

https://www.facebook.com/Centro-de-Derechos-Humanos-de-las-Mujeres-1511190289099488/

2016 Inter-American Commission on Human Rights country report on Mexico:

http://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/Mexico2016-es.pdf