Held just four days after the one-year anniversary of the Ayotzinapa disappearances, at least three hundred people attended the International Forum on Disappearances in Mexico in Mexico City from Sept. 29 to Oct. 1, 2015. Social organizations and the Autonomous Metropolitan University Campus Xochimilco brought together families of disappeared persons, human rights activists, government officials, academics, journalists and students for three days of presentations and discussion around the crisis of disappearances in Mexico. Among the participants were dozens of mothers of some of the over 26,000 thousand people who have disappeared since 2006.

Held just four days after the one-year anniversary of the Ayotzinapa disappearances, at least three hundred people attended the International Forum on Disappearances in Mexico in Mexico City from Sept. 29 to Oct. 1, 2015. Social organizations and the Autonomous Metropolitan University Campus Xochimilco brought together families of disappeared persons, human rights activists, government officials, academics, journalists and students for three days of presentations and discussion around the crisis of disappearances in Mexico. Among the participants were dozens of mothers of some of the over 26,000 thousand people who have disappeared since 2006.

The mothers listened and discussed the issues presented by government officials and civil society organizations. The mothers of Mexico’s disappeared have become experts in their own right—many have searched for their children on their own and have become the fiercest activists and critics of government impunity and state violence in Mexico.

In the face of chronic government apathy, inefficiency and even attacks, the mothers have built a community of mutual support and autonomous organizing. They have become the leaders of grassroots organization against a criminal state responsible for the disappearances of their children and thousands of others.

Adela Alvarado Valdés and Moni’s Story

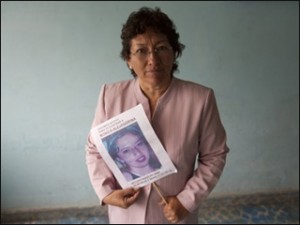

Adela Alvarado Valdés was one of the first mothers to arrive at the forum. She wore a button with a picture of her daughter, Moni. In an interview with the Americas Program, Alvarado Valdés explains that she tries her best to attend forums, events and protests for Mexico’s disappeared because “many mothers, for lack of funds or emotional strength, can’t attend events like these. I’m here because they can’t be.”

Adela Alvarado Valdés was one of the first mothers to arrive at the forum. She wore a button with a picture of her daughter, Moni. In an interview with the Americas Program, Alvarado Valdés explains that she tries her best to attend forums, events and protests for Mexico’s disappeared because “many mothers, for lack of funds or emotional strength, can’t attend events like these. I’m here because they can’t be.”

A professional clown for over 34 years, Alvarado Valdés is the mother of Monica Alejandrina Ramirez Alvarado, a psychology student who disappeared in the State of Mexico eleven years ago.

Monica disappeared on Tuesday Dec. 14, 2004 at eleven in the morning on her way to the FES Iztacala, a university in northern Mexico City. She left her home in Ecatepec in the State of Mexico, now known as one of the most dangerous states for women, with some of the highest rates of gender violence in the country, heading to the campus to turn in an assignment. At six that night, Alvarado Valdés received a call from one of her daughter’s classmates saying that Monica had never arrived at school.

Alvarado Valdés sat down with the Americas Program to detail her family’s harrowing experience searching for Monica. The eleven-year search has been marked by emotional abuse at the hands of government investigators, death threats from local police and a complete uprooting of their family life.

According to Alvarado Valdés those first days were marked by indescribable anguish. She says, “I wanted desperately to find my daughter because I felt that I could no longer live without her.”

Initially the family searched local hospitals and distributed missing person flyers, printed up with the help of the Support Center for Missing and Absent Persons (CAPEA). Four days after Monica’s disappearance, they received a menacing text message from the supposed kidnappers. They said they had Monica captive and demanded a 250,000-peso ransom. They ordered the family to deliver the money or they would cut her into pieces. Desperate, Alvarado Valdés and her family approached both a private investigator and the Federal Investigation Agency (AFI) for help returning Monica safely home.

The private investigator helped them track Monica’s cell phone activity and found that a series of phone calls were made to Jesús Martín Contreras Hernández, one of Monica’s classmates, after her disappearance. The investigator who was helping Alvarado Valdés unravel the mystery over Monica’s disappearance quit when he realized AFI was involved, since at that time it was illegal to be a private investigator in Mexico.

AFI only brought emotional stress to the family. AFI was a federal government investigation agency created by the Attorney General’s Office in 2001 to replace the notoriously corrupt Federal Judicial Police. The agency was in charge of investigating federal crimes such as kidnapping and drug trafficking. Though it was restructured in 2009 and renamed the Ministerial Federal Police, it was highly effective at finding missing persons, according to Alvarado Valdés.

In the beginning, AFI agreed to help the family find their daughter and even installed equipment in their house to train them to negotiate with the kidnappers. They prepared Alvarado Valdés’ husband to negotiate with the kidnappers and instructed them to cut off all communication with extended family and friends. She explains that the AFI investigator’s attitude changed after he trained her husband.

“He grew apathetic and very unhelpful. He basically kidnapped us in our own house and tormented us with irrelevant information, false leads and ridiculed our suffering,” explains Alvarado Valdés. Meanwhile, the family received two more text messages from the kidnappers. When Monica’s father left voice messages saying he was ready to negotiate and begging them not to hurt Monica, nobody ever called back.

The investigator began to remove the equipment he had installed in their house and when they went to complain in the AFI offices they were denied entry and were informed that their case had been closed. They then decided to travel to Mexico City with the phone logs the private investigator obtained and there a government investigator in the Attorney General’s Office ordered the arrest of Jesús Martín Contreras Hernández, in 2005. Two more men where later arrested, including Marlon Gaona, the son of a local police officer, and another man—all members of two local gangs, “Los Cruces” and “Los Gaona.” The three men were sentenced to 21 years in prison for kidnapping. They haven’t admitted to the whereabouts of Monica and to this day Alvarado Valdés and her family do not know what happened to their daughter.

During the investigation, the family uncovered a string of kidnappings and crimes associated with the Gaona family. Alvarado Valdés and her family began to raise awareness about these crimes in their neighborhood but were soon forced to move out of the Ecatepec municipality after the local police threatened them.

During the investigation, the family uncovered a string of kidnappings and crimes associated with the Gaona family. Alvarado Valdés and her family began to raise awareness about these crimes in their neighborhood but were soon forced to move out of the Ecatepec municipality after the local police threatened them.

After enduring eleven years of uncertainty, stress and emotional violence, Alvarado Valdés told the Americas Program that she has been able to stay strong because of her professional and activist families. She says her co-workers in the clown business have been very supportive. Together they have held marathon clown fairs in the Zocalo plaza and participated in events throughout the country to raise awareness about Monica’s disappearance and the serious human rights crisis in Mexico. And as a staunch activist for disappeared persons, Alvarado Valdés has forged friendships and relationships with other mothers.

“It’s been eleven years since Monica disappeared and I refuse to forget about her. We didn’t lose a dog, a car, or a bicycle. But a human being, my daughter, and I can’t abandon her. I don’t think we families can ever abandon our disappeared loved ones to their fate,” Alvarado Valdés told the Americas Program.

“Unfortunately, over the years we have learned that this crisis has worsened because the government and mafias profit from disappearances.”

Despite years of hardship, Alvarado Valdés remains determined to attain justice for Monica and help other families do the same. Her horrible experience with AFI helped her develop an acute awareness of the costs of government inaction and complicity in these cases.

“We’ve succeeded in sentencing those three men. But we couldn’t achieve more than that. You can’t do more because the government protects these criminals. When I get together with other families, with my friends and fellow victims, we all realize that our own government is contributing to this terrible crisis,” explained Alvarado Valdés at the conclusion of the forum.

Norma Andrade and the Long Battle for Justice for Disappeared Women

As one of the founding members of May Our Daughters Return Home, a Mexican non-profit association of mothers whose daughters have been victims of femicide in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Norma Andrade is very familiar with the emotional hardships, tireless work and violence many mothers and families face in the search for their missing children. Andrade’s daughter, Lilia Alejandra García Andrade was disappeared on Feb. 14, 2001 in Ciudad Juarez. Seven days later Lilia’s body was found wrapped in a blanket, with signs of physical and sexual assault.

As one of the founding members of May Our Daughters Return Home, a Mexican non-profit association of mothers whose daughters have been victims of femicide in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Norma Andrade is very familiar with the emotional hardships, tireless work and violence many mothers and families face in the search for their missing children. Andrade’s daughter, Lilia Alejandra García Andrade was disappeared on Feb. 14, 2001 in Ciudad Juarez. Seven days later Lilia’s body was found wrapped in a blanket, with signs of physical and sexual assault.

Since then Andrade has become a fearless activist in Ciudad Juarez and has led the organization of mothers for over fourteen years in the hopes of getting the murderers of their daughters arrested and convicted.

To date Andrade’s unrelenting activism has led to two attacks on her life. On Friday Dec. 2, 2011, Andrade was shot and wounded in her home in Ciudad Juarez by an unknown assailant. Shortly afterwards she moved to Mexico City for her safety. However, two months later, Andrade was again attacked by an unknown assailant outside her residence in the Coyoacán neighborhood while she was taking her granddaughter to school. The attacker slashed Andrade in the face with a knife.

Since 2008 and especially after the second attack on Norma’s life, International human rights and women’s groups including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Nobel Women’s Initiative have called for immediate and effective protection for Norma Andrade and her family.

Despite these attacks and other threats against her life, Andrade has continued to organize in Ciudad Juarez for justice for victims of femicide. In a country where attention to femicides is minimal and where there are very few advances in investigations due to corruption and a lack of political will, Andrade is an activist and mother who has taken it upon herself to learn how to overcome bureaucratic barriers and apathy to seek justice for disappeared women. She has accompanied and advised families to investigate disappearances, promoted occupational therapy for grief-stricken families, lobbied to change laws under the Penal Code of the State of Chihuahua that allow this and other violence and has become an international figure and spokesperson against the violation of women’s human rights in Mexico.

More recently she joined the Task Force for Human Rights and Social Justice to organize workshops for middle and high school girls in Ciudad Juarez focused on preventing disappearances. The workshops are focused on telling the stories of how three young girls disappeared and to teach young girls how to identify, prevent and denounce potential kidnappers.

Following her presentation at the forum, the Americas Program asked Andrade, what drives her tireless work against femicide and disappearances in northern Mexico.

Following her presentation at the forum, the Americas Program asked Andrade, what drives her tireless work against femicide and disappearances in northern Mexico.

“I found my daughter murdered 14 years ago, and that’s the same amount of time that I’ve been organizing. And I’ve learned a lot along the way. I knew nothing about law but I now know how to ground my demands and the rights that we are seeking. When we say we have the right to life, we know which clause in the constitution guarantees that right. I can’t say that a femicide gets 60 years of prison time for their crime if I don’t know the penal code and now I know the definition of femicide, I know what femicide means—we’ve learned all this along the way, through organizing,” Andrade said.

According to Andrade, there is still much to do to prevent crimes against women and attain justice. When Mexico and the entire world learned of the disappearances of 43 teachers’ college students from Guerrero last September, Andrade pointed to the case of Navajo Creek in Chihuahua, where the remains of 80 people have been uncovered in the last two years, most of them women apparently victims of sex trafficking.

“Eighty remains have been identified at Navajo Creek. Almost double the 43. And it’s worth asking ourselves why 43 moves people and not 80,” Andrade stated.

While she acknowledges that there is indifference towards the disappearances of poor women, Andrade believes that people have to come together in the search for justice for all the disappeared persons of Mexico, from the Ayotzinapa 43 to the victims of femicide.

“What I think is fundamental is unity. Unity between states, unity between mothers, because what unites us is the same pain. Even when the missing are men, the pain felt over the loss of a son is the same pain felt as the result of the loss of a daughter,” explains Andrade.

Berta Nava, Ayotzinapa and Solidarity Among Families of the Disappeared

Berta Nava is the mother of many disappeared youth. When her son Julio César Ramírez Nava was murdered on the night of Sept. 26, 2014 in Iguala, Guerrero, she adopted the cause of the forty-three disappeared students of the Raul Isidro Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa as her own.

Berta Nava is the mother of many disappeared youth. When her son Julio César Ramírez Nava was murdered on the night of Sept. 26, 2014 in Iguala, Guerrero, she adopted the cause of the forty-three disappeared students of the Raul Isidro Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa as her own.

Nava is a stay-at-home mother who after losing her twenty-three year old son Julio, a first year student at the Ayotzinapa School, has become a fierce and courageous voice among the parents of the disappeared students of Ayotzinapa. For over a year she has participated in marches, panels, and interviews demanding the safe return of the 43 teachers’ college students from Ayotzinapa.

As one of the mothers of Ayotzinapa at the forum, Nava explains why it is important to learn from and show support to other mothers and families. “It’s very important to be here with them, to listen to their struggles and journey, how they have been organizing, what they do to continue fighting, where they find their strength to carry on. Because my strength, rage, indignation and hope is what helps me continue fighting—the hope to find them alive,” explains Nava.

It’s been a year since the disappearance of the Ayotzinapa students—now the most emblematic and publicized case of disappearances in the history of the country. When speaking of the anniversary, Nava expresses herself with the resolve and frustration characteristic of many other mothers, many of whom have searched for their children for much longer.

“Many are saying that one year is a long time. But for us, no time has passed at all. We are still living on the night of the 26th. For us time is at a standstill. For us it is the same day when our children were disappeared. In my case, I had to go to the morgue to claim my son’s body. I never thought I would have to go recognize his body. But we’re still here, to ensure that the death of my son and the disappearances of these young men doesn’t stay in impunity.”

A National Crisis

What ties mothers like Alvarado, Andrade and Nava isn’t only the pain of losing a child but the indignation toward a government that has permitted impunity, corruption and violence to take the lives of thousands of Mexicans. It is a shared pain and indignation that has declared the State as the prime suspect for the disappearances and murders of Monica, Lilia, Julio César and thousands more unnamed victims.

What ties mothers like Alvarado, Andrade and Nava isn’t only the pain of losing a child but the indignation toward a government that has permitted impunity, corruption and violence to take the lives of thousands of Mexicans. It is a shared pain and indignation that has declared the State as the prime suspect for the disappearances and murders of Monica, Lilia, Julio César and thousands more unnamed victims.

The UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, visited Mexico in October and issued a stark assessment of the state of human rights in the country. He met with President Enrique Peña Nieto, other government officials, and with NGOs and civil society. What the Commissioner found is a reality that many mothers of disappeared persons in Mexico are all too familiar with.

Al Hussein concluded that Mexico is a society that is racked by high levels of insecurity, disappearances and killings. He noted that at least 151,233 people have been killed between Dec. 2006 and Aug. 2015 and at least 26,000 have gone missing—although activist and non-governmental organizations like Services and Consulting for Peace (SERAPAZ) say the real figure is much higher.

The official figure of “people not found” in Mexico since 2006 has fluctuated under the Peña administration. The contradictory figures released by the Mexican government, and the information labyrinth that investigators and human rights activists must embark on to track disappearances, gets to the core of Mexico’s human rights crisis. The ineptitude and reluctance with which the Mexican government has approached the disappearances crisis reflects a structural problem in Mexico. It is a state policy to use impunity, corruption, and ineffectual judicial mechanisms and investigations to sustain violence and terror—to sustain, or ignore, the human rights crisis of disappearances.

In the press conference, Al Hussein explained that his visit to Mexico was “sobering with regard to the daily realities for millions of people here in Mexico.” According to the Commissioner, “It is neither myself, my office, the UN, nor State officials who can declare enough is being done or has been done. It is only the people who can do this, especially the most disadvantaged, the victims or families of victims of crime who have the credibility to pass judgment.”

At the conclusion of the International Forum on Disappearances in Mexico, Andrade judged the Mexican government as responsible for her and thousands of other mothers’ suffering. “What must unite us is this pain, a united front against our common enemy, which is the State, our real enemy, even over any criminal group involved in these cases,” concluded the activist.

“If we don’t come together, if we don’t organize, the government will do away with all of us, one by one,” Nava added. “Because that is its goal—to fragment our movements, to prevent us from coming together and sharing our pain, our ways of organizing. But it is very important to be united in a cause that seeks justice for everyone,” she explained.

In the face of an increasingly violent government with little regard for human rights, Nava believes now is a crucial time to join as families of disappeared persons and as a country seeking justice for its disappeared.

“We’re going to continue fighting, every day. For our children, so we can once again see our children safe and sound, and so other families are reunited with their children as well. We want families united. So that tomorrow, we can all be happily together again,” concluded Nava.

Nidia Bautista is the managing director for the CIP Americas Program and writes about student protest, transborder social movements, and gender issues in Latin America.

Editor: Laura Carlsen