By David Bacon

Editor’s Note: This is the third and final installment of a three-part series on migrant rights by journalist and immigration activist David Bacon. This article is taken from the report “Displaced, Unequal and Criminalized – Fighting for the Rights of Migrants in the United States” that examines the origins of the current migratory labor phenomenon, the mechanisms that maintain it, and proposals for a more equitable system. The Americas Program is proud to publish this series in collaboration with the author.

Development of the Immigrant Rights Movement to 1986

Before the cold war, the defense of the rights of immigrants in the U.S., especially those from Mexico, Central America and Asia was mounted mostly by immigrant working class communities, and the alliances they built with the left wing of the U.S. labor movement. At the time when the left came under attack and was partly destroyed in the cold war, immigrant rights leaders were also targeted for deportation. Meanwhile, U.S. immigration policy became more overtly a labor supply scheme than at any other time in its history.

In the 1950s, at the height of the cold war, the combination of enforcement and contract labor reached a peak. In 1954 1,075,168 Mexicans were deported from the U.S. And from 1956 to 1959, between 432,491 and 445,197 Mexicans were brought into the U.S. each year on temporary work visas, in what was known as the “bracero” program. The program, begun during World War Two, in 1942, was finally abolished in 1964.

The civil rights movement ended the bracero program, and created an alternative to the deportation regime. Chicano activists of the 1960s – Ernesto Galarza, Cesar Chávez, Bert Corona, Dolores Huerta and others – convinced Congress in 1964 to repeal Public Law 78, the law authorizing the bracero program. Farm workers went on strike the year after in Delano, California, and the United Farm Workers was born. They also helped to convince Congress in 1965 to pass immigration legislation that established new pathways for legal immigration – the family preference system. People could reunite their families in the U.S. Migrants received permanent residency visas, allowing them to live normal lives, and enjoy basic human and labor rights. Essentially, a family- and community-oriented system replaced the old labor supply/deportation program.

Then, under pressure from employers in the late 1970s, Congress began to debate the bills that eventually resulted in the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. That debate set in place the basic dividing line in the modern immigrant rights movement. IRCA contained three elements. It reinstituted a bracero-like guest worker program, by setting up the H2-A visa category. It penalized employers who hired undocumented workers (“employer sanctions”), and required them to check the immigration status of every worker. And it set up an amnesty process for undocumented workers in the country before 1982.

The main trade union federation to which most U.S. unions belong, the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), supported sanctions, saying they’d stop undocumented immigration (and therefore, presumably, job competition with citizen or legal resident workers). The Catholic Church and other Washington DC liberal advocates supported amnesty and were willing to agree to guest workers and enforcement as a tradeoff. Employers wanted guest worker programs. The bill was opposed by immigrant communities and leftwing immigrant rights advocates, from the Centro de Acción Social Autónomo (CASA), founded in Los Angeles by labor and immigrant rights leader Bert Corona, to the Bay Area Committee Against Simpson Mazzoli in Northern California, and similar groups around the country. Local labor activists and leaders also opposed the bill, but were not strong enough to change labor’s position nationally. The Washington DC-based coalition produced the votes in Congress, and Ronald Reagan, one of the country’s most conservative presidents, signed the bill into law.

Once the bill had passed, many of the local organizations that had opposed it set up community-based coalitions to deal with the bill’s impact. In Los Angeles, with the country’s largest concentration of undocumented Mexican and Central American workers, pro-immigrant labor activists set up centers to help people apply for amnesty. That effort, together with earlier, mostly left-led campaigns to organize undocumented workers, built the base for the later upsurge of immigrants that changed the politics and labor movement of the city. Elsewhere, local immigrant advocates set up coalitions to look for ways to defend undocumented workers against the impact of employer sanctions. Grass roots coalitions then began helping workers set up centers for day laborers, garment workers, domestic workers, and other groups of immigrants generally ignored by established unions.

Over the 27 years since IRCA, a general division has marked the U.S. immigrant rights movement. On one side are well-financed advocacy organizations in Washington DC, with links to the Democratic Party and large corporations. They formulate and negotiate over immigration reform proposals that combine labor supply programs and increased enforcement against the undocumented. On the other side are organizations based in immigrant communities, and among labor and political activists, who defend undocumented migrants, and who resist proposals for greater enforcement and labor programs with diminished rights.

In the late 1990s, when the Clinton administration acquiesced in efforts to pass repressive immigration legislation (what eventually became the Immigration Reform And Immigrant Responsibility Act), Washington lobbying groups advocated a strategy to allow measures directed at increasing deportations of the undocumented to pass (calling them “unstoppable”) while mounting a defense only of legal resident immigrants. Many community-based coalitions withdrew from the Washington lobbying efforts, refusing to cast the undocumented to the wolves. The strategy failed, in any case, and the eventual law includes severe provisions directed at legal, as well as undocumented immigrants.

In the labor movement, the growing strength of immigrant workers, combined with a commitment to organize those industries where they were concentrated, created the base for changing labor’s position. At the 1999 AFL-CIO convention in Los Angeles, the federation called for the repeal of employer sanctions, for a new amnesty, and for defending the labor rights of all workers. The federation was already opposed to guest worker programs. That position was maintained by the AFL-CIO, even after several unions left to form the rival Change to Win federation, until 2009. At that time, a compromise was reached between the two federations, in which they dropped their previous opposition to employer sanctions, so long as they were implemented “fairly.”

In the years between 2003 and 2009, a succession of “comprehensive” immigration reform bills were introduced into Congress. At their heart are the guest worker programs proposed by employers. But while the employer lobbies wrote the first bills, they’ve been supported by a political coalition that includes some unions, beltway immigrant advocacy groups, and some churches. Except for the vacillating and divided position of unions, this is the same political coalition that passed IRCA in 1986.

Some local immigrant rights coalitions have also supported the bills, although most have been unwilling to agree to guest worker programs and more enforcement. Supporters of the comprehensive bills have organized a succession of high-profile lobbying efforts, which received extensive foundation support. The structure of the bills has been basically the same from the beginning – the same three-part structure of IRCA – guest workers, enforcement and some degree of legalization.

Over the last decade, however, a loose, unorganized network of groups has grown that has generally opposed most CIR bills and their provisions, and that have also organized the movements on the ground that have opposed increased enforcement and repression directed against immigrant communities. Outside the Washington beltway, community coalitions, labor and immigrant rights groups are advocating alternatives. Some of them are large-scale counters to the entire CIR framework. Others seek to win legal status for a part of the undocumented population, as a step towards larger change.

The DREAM Act

One of those proposals is the Dream Act. First introduced in 2003, the bill would allow undocumented students graduating from a U.S. high school to apply for permanent residence if they complete two years of college or serve two years in the U.S. military. Estimates are that it would enable over 800,000 young people to gain legal status, and eventual citizenship. For seven years thousands of young “sin papeles,” or people without papers, have marched, sat-in, written letters and mastered every civil rights tactic to get their bill onto the Washington DC agenda.

Many of them have “come out” — declaring openly their lack of legal immigration status in media interviews, defying authorities to detain them. Three were arrested when they sat-in at the office of Arizona Senator John McCain, demanding that he support the bill, while defying immigration authorities to come get them. The DREAM Act campaigners did more than get a vote in Washington. They learned to stop deportations in an era when more people have been deported than ever since the days of the Cold War.

When it was originally written, the bill would have allowed young people to qualify for legalization with 900 hours of community service, as an alternative to attending college, which many can’t afford. However, when the bill was introduced, the Pentagon pressured to substitute military for community service. Many young activists were torn by this provision, and ultimately, the bill did not pass Congress, even with that change. Nevertheless, many immigrant rights activists view the DREAM Act as an important step towards a more basic reform of the country’s immigration laws.

Supporting the Dream Act and other partial protections for the undocumented are the worker centers around the country. This movement is based on organizing centers for contingent workers, who are mostly undocumented. Some of the centers have anchored the protests against repression in Arizona, or fought to pass laws in California, New York and elsewhere prohibiting police from turning over people to immigration agents. They’ve especially developed grassroots models for organizing migrants who get jobs on street corners, and these projects have come together in the National Day Labor Organizing Network. The National Domestic Worker Alliance was organized last year, in part using the experience of day labor organizing, to win rights for domestic workers, almost all of whom are women. It won passage of a bill of rights in New York, and is working on passing it in California.

On a broader scale, what would be a law that would liberate people- not turn them into modern day slaves- today? Many progressive immigrant rights organizations have sought to formulate an answer to this question, especially in response to the CIR proposals in Washington that they oppose.

Advocating New Policies- Progressive Proposals

The Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales (Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations – FIOB) conducted a series of organized discussions among its California chapters to formulate a very progressive position on immigration reform, with the unique perspective of an organization of migrants and migrant-sending communities. Because of its indigenous membership, FIOB campaigns for the rights of migrants in the U.S. — for immigration amnesty and legalization for undocumented migrants — while also condemning proposals for guest worker programs. At the same time, “we need development that makes migration a choice rather than a necessity — the right to not migrate,” explains Gaspar Rivera Salgado, FIOB’s binational coordinator. “Both rights are part of the same solution. We have to change the debate from one in which immigration is presented as a problem to a debate over rights. The real problem is exploitation.” This perspective is especially important in the U.S., where those debating immigration policy need to hear the voices of Mexicans, especially on the left, as they discuss the movement of people back and forth across the border.

The FIOB proposal on immigration reform is similar to that advanced by the Dignity Campaign, a loose coalition of organizations around the country that have proposed an alternative to the comprehensive (labor supply plus enforcement) bills. The constituent organizations have participated in other earlier coalitions opposing employer sanctions and guest worker programs. The Dignity Campaign brings together immigrant rights and fair trade organizations, to encourage each to see the global connections between trade policy, displacement and migration. It also brings together unions and immigrant rights organizations to spur the growth of a fight back against immigration enforcement against workers, highlighting the need to oppose the criminalization of work.

The Dignity Campaign proposal draws on previous proposals, particularly one put forward by the American Friends Service Committee called “A New Path,” — a set of moral principles for changing U.S. immigration policy. Several other efforts were also made earlier by the National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights to define an alternative program and bring together groups around the country to support it. Important contributions to the Dignity Campaign were made by many other organizations, listed on its website, www.dignitycampaign.org.

The critique shared by all these organizations contends that the CIR framework ignores trade agreements like NAFTA and CAFTA, which produce profits for U.S. corporations, but increase poverty in Mexico and Central America. Without changing U.S. trade policy and ending structural adjustment programs and neoliberal economic reforms, millions of displaced people will continue to come, no matter how many walls are built on the border.

Under the “comprehensive immigration reform” (CIR) proposals promoted by Washington DC advocacy groups for several years, some of which were introduced as bills into Congress, people working without papers would continue to be fired and even imprisoned and raids would increase. Vulnerability makes it harder for people to defend their rights, organize unions and raise wages. That keeps the price of immigrant labor low. This will not stop people from coming to the U.S., but it will produce a much larger detention system. Last year over 350,000 people went through privately-run prisons for undocumented immigrants. At the same time, the Washington DC-based CIR proposals all expand guest worker programs, in which workers would have few rights, and no leverage to organize for better conditions. Finally, the CIR legalization measures would impose barriers making ineligible many of the 12 million people who need legal status. They condition legalization on “securing the border,” which has become a Washington DC euphemism for a heavy military presence augmenting 20,000 Border Patrol agents, creating a climate of wholesale denial of civil and human rights in border communities.

“The governments of both Mexico and the U.S. are dependent on the cheap labor of Mexicans. They don’t say so openly, but they are,” Rufino Domínguez concludes. “What would improve our situation is legal status for the people already here, and greater availability of visas based on family reunification. Legalization and more visas would resolve a lot of problems – not all, but it would be a big step,” he says. “Walls won’t stop migration, but decent wages and investing money in creating jobs in our countries of origin would decrease the pressure forcing us to leave home. Penalizing us by making it illegal for us to work won’t stop migration, since it doesn’t deal with why people come.”

Changing corporate trade policy and stopping neoliberal reforms is as central to immigration reform as gaining legal status for undocumented immigrants. It makes no sense to promote more free trade agreements, and then condemn the migration of the people they displace. Instead, Congress must end the use of the free trade system as a mechanism for producing displaced workers. That also means delinking immigration status and employment. If employers are allowed to recruit contract labor abroad, and those workers can only stay if they are continuously employed, then they will never have enforceable rights.

The root problem with migration in the global economy is that it’s forced migration. A coalition for reform should fight for the right of people to choose when and how to migrate. Freedom of movement is a human right. Even in a more just world, migration will continue, because families and communities are now connected over thousands of miles and many borders. Immigration policy should therefore make movement easier.

At the same time, workers need basic rights, regardless of immigration status. It would be better to devote more resources to enforcing labor standards for all workers, instead of penalizing undocumented workers for working, and employers for hiring them. “Otherwise,” Domínguez says, “wages will be depressed in a race to the bottom, since if one employer has an advantage, others will seek the same thing.”

To raise the low price of immigrant labor, immigrant workers have to be able to organize. Permanent legal status makes it easier to organize. Guest worker programs, employer sanctions, enforcement and raids make organizing much more difficult. Today the section of workers with no benefits and the lowest wages is expanding the fastest. Proposals to deny people rights or benefits because of immigration status make this process move even faster. A popular coalition should push back in the other direction, toward more equal status, which will help unite diverse communities.

Building a political coalition for a more pro-worker and pro-immigrant reform has to start by seeking mutual interest among workers. That common ground is a struggle for jobs and rights for everyone. Black unemployment, for instance, is at catastrophic levels. Very little unemployment is a result of displacement by immigrants, and is caused mostly by the decline in manufacturing and cuts in public employment. In the 2001 recession 300,000 out of 2,000,000 Black factory workers lost their jobs. But in the growing service and high tech industries, displaced African American and Chicano workers are anathema. Employers think they’re too pro-union. They demand high wages the companies don’t want to pay.

It’s not possible to win major changes in immigration policy without making them part of a struggle for the goals of African Americans, unions and working-class communities. To end job competition, for instance, workers need Congress to adopt a full-employment policy. To gain organizing rights for immigrants, all workers need the Employee Free Choice Act and labor law reform. Winning those demands requires an alliance between workers – immigrants and native-born, Latinos, African Americans, Asian Americans and whites. An alliance with employers, giving them new guest worker programs, will increase job competition, push wages down, and make affirmative action impossible.

The Dignity Campaign proposal, therefore, is not just an alternative program for changing laws and policies, but an implicit strategy of alliances among those communities and constituencies based on their mutual interest. The basic elements of such an alternative include:

* Giving permanent residence visas, or green cards, to undocumented people already here, and expanding the number of green cards available for new migrants.

* Eliminating the years-long backlog in processing family reunification visas, strengthening families and communities.

* Allowing people to apply for green cards, in the future, after they’ve been living in the U.S. for a few years.

* Ending the enforcement that has led to thousands of deportations and firings

* Repealing employer sanctions, and enforcing labor rights and worker protection laws, for all workers.

* Ending all guest worker programs

* Dismantling the border wall and demilitarizing the border, so more people don’t die crossing it, and restoring civil and human rights in border communities.

* Responding to recession and foreclosures with jobs programs to guarantee income, and remove the fear of job competition

* Redirecting the money spent on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to rebuilding communities, refinancing mortgages, and restoring the social services needed by working families.

* Renegotiating existing trade agreements to eliminate causes of displacement and prohibiting new trade agreements that displace people or lower living standards, including military intervention intended to enforce neoliberal reforms.

* Prohibiting local law enforcement agencies from enforcing immigration law, ending roadblocks, immigration raids and sweeps, and closing detention centers

There is no shortage of needed work in the U.S., but budget priorities must be changed to redirect resources to the areas that will produce jobs and increased well-being. To resolve the dilemmas of migration and globalization, the U.S. needs a system that produces security, not insecurity. Corporations and those who benefit from current priorities might not support this alternative, but millions of people will.

A new era of rights and equality for migrants won’t begin from Washington DC, any more than the civil rights movement did. A human rights reform will be a product of the social movements of this country, especially of people on the bottom outside the beltway. A social movement made possible advances in 1965 that were called unrealistic and politically impossible a decade earlier. The Dignity Campaign proposal may not be a viable one in a Congress dominated by Tea Party nativists and corporations seeking guest worker programs. But just as it took a civil rights movement to pass the Voting Rights Act, any basic change to establish the rights of immigrants will also require a social upheaval and a fundamental realignment of power.

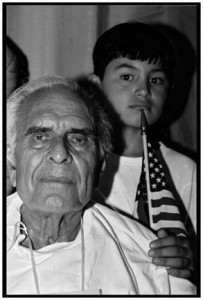

David Bacon is a writer and photojournalist based in Oakland and Berkeley, California. He has been a reporter and documentary photographer for 18 years, shooting for many national publications. He has exhibited his work nationally, and in Mexico, the UK and Germany. Bacon covers issues of labor, immigration and international politics and is an associate editor at Pacific News Service and a regular contributor to the Americas Program.

The report “Displaced, Unequal and Criminalized – Fighting for the Rights of Migrants in the United States” was prepared for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.