With the Mexican Consulate as a backdrop, at least two hundred people in Los Angeles organized skits, marched and chanted in protest of Enrique Peña Nieto’s meeting with President Obama in Washington on Jan. 6. Meanwhile, hundreds of protestors gathered on Lafayette Square in Washington DC, while some met with members of Congress to ask them to cut US security aid to Mexico.

With the Mexican Consulate as a backdrop, at least two hundred people in Los Angeles organized skits, marched and chanted in protest of Enrique Peña Nieto’s meeting with President Obama in Washington on Jan. 6. Meanwhile, hundreds of protestors gathered on Lafayette Square in Washington DC, while some met with members of Congress to ask them to cut US security aid to Mexico.

Los Angeles was one of forty US cities that protested Enrique Peña Nieto’s visit to the White House, his first as president. Undocumented migrants, students, activists, mothers and workers came out by the hundreds to protest the failure of the War on Drugs that has caused the disappearance and death of thousands of Mexicans and to call for the resignation of Enrique Peña Nieto. Called by the #USTired2 national day of action, protests in Los Angeles showed that the drug war violence and corruption in Mexico have spurred Mexican communities all over the world to action, despite borders.

Many protestors wore t-shirts and face paint in homage to the 43 disappeared students from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college, attacked in Iguala, Guerrero. They shouted “Ayotzi, Ayotzi Los Angeles is with you!” and other slogans in English and Spanish that implicated both President Obama and Enrique Peña Nieto in the on-going violence in Mexico.

Belén Asención, a resident of Los Angeles and migrant, detailed her harrowing experience after the disappearance of her brother in Puebla. For over four years her family has searched for her brother. Belen’s mother went to the military to ask for help. She said the military told her to stop searching, saying it was too dangerous. In tears, Belen asked, “How can the Mexican government tell more than 120,000 mothers not to look for their loved ones?”

Belen’s brother is just one of thousands of cases of missing people in Mexico, and just like the families of the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa, she has been forced to search for her brother with no real support from the Mexican government.

Belen, a small woman dressed in jeans and a sweater, wrestled to overcome her shyness upon taking the microphone but spoke firmly as she told her story of how her brother’s disappearance had devastated her family, and denounced President Obama’s neglect of human rights and the Mexican government’s unwillingness to intervene in the country’s violence.

Belen, a small woman dressed in jeans and a sweater, wrestled to overcome her shyness upon taking the microphone but spoke firmly as she told her story of how her brother’s disappearance had devastated her family, and denounced President Obama’s neglect of human rights and the Mexican government’s unwillingness to intervene in the country’s violence.

“President Obama talks about human rights yet he funds the repression of thousands of people. And he has the nerve to talk to a man who is responsible for the murder, torture and disappearance of thousands of Mexicans.”

She continued, “The Mexican government pretends to have everything under control yet they can’t tell me the whereabouts of my brother.” Other people also came up to tell about experiences with violence at the hands of Mexico’s military and police forces.

During the rally, protestors handed a petition to the Mexican Consulate of Los Angeles that demanded the resignation of Enrique Peña Nieto and the destitution of Mexican counsel Carlos Sada, claiming both officials have been unresponsive to the Mexican communities’ demand for justice in the Ayotzinapa case. Demonstrators also called for the liberation of political prisoners Nestora Salgado and José Manuel Mireles, both members of self-defense forces in Guerrero and Michoacan, respectively.

The L.A.-Ayotzinapa Link

The U.S. nationwide mobilization for justice in Mexico isn’t without precedents. As the second largest Mexican city in the world, Los Angeles is home to over one million Mexican-born migrants and Mexican-Americans. Mexicans make up the majority of the Latino population, approximately 78 percent, while Salvadoran and Guatemalan migrants make up most of the rest of the Latino community. Many people travel back and forth between Mexico and like other Mexican communities throughout the U.S., Los Angeles residents send millions of dollars in remittances to family in Mexico; in 2012 nationwide remittances were $22.4 billion.

The Ayotzinapa disappearances pulled at the heart of the Mexican migrant community in Los Angeles and reawakened many people’s memories of the corruption, violence, and poverty that forced them to flee north. Concepción Gómez Avilés attended the protest with her high-school aged son, sporting an Inmigrantes Unidos en Resistencia t-shirt for the LA-based migrant organization she participates in. Concepción migrated from Puebla, a state in southern Mexico, where she still has family.

“As a parent, who would want to undergo the pain of the parents of the 43 normalistas?” she said, explaining that as a mother she felt compelled to protest, in an interview with the Americas Program.

For Concepción, as for many the criticism of Peña Nieto predates the Ayotzinapa case. “We’re against the violence in Mexico and against Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency because he stole the elections, because he was not elected and it was a political imposition. Since he rose to power we’ve been organizing and have stood against each reform he has implemented in the past two and a half years. Many people tell us that what goes on in Mexico does not affect us because we are far, but it affects our families still living in Mexico. It’s true that it doesn’t affect us because we’ve already left, but it strongly affects our families who sometimes ignore the corruption and violence of this government because they receive support from it, which is all a farce. They are bought off with that support. They’re implementing reforms that happen to be illegal and get no opposition from the Mexican people because they offer them donations and supposed help, which is all fraud.”

Concepción refers to Mexican political parties’ and government’s coercive strategy of buying the political support of predominantly poor communities through donations, gifts and money, especially by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that ruled for 71 years continuously and has now returned to power under Peña Nieto. During Enrique Peña Nieto’s electoral campaign in 2012 the PRI handed out Soriana grocery cards and money cards in exchange for votes. Concepción highlights a growing group of Mexicans on both sides of the border who are protesting corruption and focusing on the influence and power migrant communities in the US have to change their communities and families still in Mexico.

“As the main providers of financial stability to our families, through the consistent remittances we send them, we must inform them and encourage them to think critically. I tell my family that if they decide to take the government’s help they can no longer count on my financial support. I tell them that while the government might give them beans and rice for a day, I give them financial stability on a monthly basis. I’ve told them that if they prefer to gather the crumbs handed out by the government, then they’ll no longer receive my help,” stated Concepcion.

“As the main providers of financial stability to our families, through the consistent remittances we send them, we must inform them and encourage them to think critically. I tell my family that if they decide to take the government’s help they can no longer count on my financial support. I tell them that while the government might give them beans and rice for a day, I give them financial stability on a monthly basis. I’ve told them that if they prefer to gather the crumbs handed out by the government, then they’ll no longer receive my help,” stated Concepcion.

While direct family and political ties link Mexican communities across the border, solidarity from other Latin American migrant communities also thrives in Los Angeles.

Ana Maria, a migrant mother originally from El Salvador, went to the march to support her Mexican husband and children.

“I’m Salvadoran and what’s happening in Mexico now looks a lot like what happened in El Salvador during the civil war. The disappearance of the students moved me to action because I’ve put myself in the place of the families who have unjustly lost their children, and as a mother, if something were to happen to my children, I would seek justice. What is happening in Mexico now is terrible. If people don’t organize now, they will see no justice. We must organize now to see change.”

Ana Maria’s husband Blas is an organizer in the migrant worker community and has taken part in the protests to support Mexican social movements, including the self-defense groups of Michoacan, community police in Guerrero and more recently the demand for justice in Ayotzinapa. Blas believes that he has a responsibility as a Mexican living in the United States to use his free speech to denounce the Enrique Peña Nieto government.

“We come out and protest because we know it isn’t repressive here the way it is in Mexico. We have the opportunity to protest,” he explained. “Here we have this power to influence the awareness of our people in Mexico and show them our solidarity, even though the media pretends it doesn’t exist.”

Xalli, a Mexican organizer and original member of the #YoSoy132LosAngeles collective organized in 2012, read off some of the demands of the Mexican community to the local press after the rally.

“I am Mexican and I have been living here for over ten years. Since the 2012 elections we’ve been staging protests against the imposition of Enrique Peña Nieto and since then we have continued to organize against all the violence and corruption under his government,” Xalli told the Americas Program at Tuesday’s protest.

Like others at the protest, Xalli points out the importance the Mexican diaspora plays in supporting the fight against Mexico’s corruption and violence from abroad.

“It’s very important that our fellow Mexicans in Mexico see us protesting outside of the country, and especially in the United States, because it’s a way of showing them our support. It shows them that we are very aware of what is happening in our home country and that we know what’s going on.” She also noted the role of social media networks in spreading news about Mexico sometimes even before it comes out in the Mexican media.

At the L.A. rally, many first and second generation Mexican-Americans also expressed high awareness of the problems of corruption and violence in Mexico and have jumped into action.

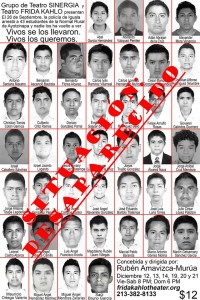

Katie Ventura, an artist and educator based in Los Angeles, acts in a new play that pays homage to the missing students and encourages dialogue among the mainly Mexican-American audience. The play, put on by a collective of Latino and Mexican actors in the Frida Kahlo Theater in downtown Los Angeles, places a collection of the 43 students’ family and friend testimonies on center stage.

“My experiences as a first generation Mexican American daughter of migrant parents, and my travelling experience in several Mexican states gives me a greater connection to the nation as a whole.” On her study-abroad experience in Mexico, Katie traveled and lived in Guerrero, in a community only 200 kilometers from Ayotzinapa. She says the experience inspired her to create the representations of the mothers of the missing students and pay homage to them every night as they rehearse and perform.

Katie, like many L.A.-based activists and artists, believe that people across the Americas are all connected to the same struggles. While some manifest solidarity through protest, Katie has found her outlet through the performing arts. She explains, “My act of solidarity is through performance and informing others after the show that the simple act of taking a standpoint on an issue is far more valuable than just staying neutral or uninformed.”

Katie, like many L.A.-based activists and artists, believe that people across the Americas are all connected to the same struggles. While some manifest solidarity through protest, Katie has found her outlet through the performing arts. She explains, “My act of solidarity is through performance and informing others after the show that the simple act of taking a standpoint on an issue is far more valuable than just staying neutral or uninformed.”

The organizers behind the artistic and political mobilization in Los Angeles for justice in Ayotzinapa and against Enrique Peña Nieto say the movement will continue strong this year. The play “Situación: Desaparecido” is set to present shows in Los Angeles and Tijuana this month. And activists and organizations in the city also plan to host more mobilizations in synch with protests in Mexico in support of the parents of the 43 missing students.

The actions, coordinated by #USTired2, have helped illuminate the political solidarity present among communities linked by history, violence, solidarity and ultimately, by hope. It has been an initiative that has catalyzed dozens of existing organizations to protest U.S. foreign policy toward Mexico and awaken empathy and the action of Mexicans living in the US.

These nationwide protests have given activists, artists, and migrant communities a forum for discussion and hammering out new political strategies in the fight for justice in Mexico. And as the Los Angeles demonstrations prove, the historically politicized Mexican and pan-Latin American diaspora have become a unified actor in the growing fight for justice in Mexico from abroad.

Pictures by Andre Medina