He’s been sitting in bed for hours. When exhaustion threatens to overtake him, he uses the wall to push himself up to stand. He walks a few steps, two or three at most, and returns to his seat. He begins to tell the story of his time in prison (in Oaxaca, Altiplano and Chilpancingo), without leaving out how he was tortured when the state police apprehended him in Tixtla.

He’s been sitting in bed for hours. When exhaustion threatens to overtake him, he uses the wall to push himself up to stand. He walks a few steps, two or three at most, and returns to his seat. He begins to tell the story of his time in prison (in Oaxaca, Altiplano and Chilpancingo), without leaving out how he was tortured when the state police apprehended him in Tixtla.

Gonzalo Molina talks and talks with the reporter, to say all he can before his memory fails and he forgets why he is here, confined to a 2 meter by 3 meter cell, with only a bed, a chair, a jug of water and a shelf where his documents are piled.

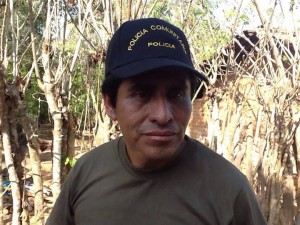

When he returns to his seat, the former leader of the Tixtla community police, Gonzalo Molina Gonzalez, reaches out to grab the bag of peanuts that he offers to the visitors who come to talk to him about his time in prison.

“When I got to Oaxaca I was deemed a high-risk offender; as such, when my case was before the courts, the army, marines and federal police mounted special operations and did not allow my family to get near me. They also took me out in a bullet-proof vest, while transferring me they had me kneel in the patrol cars, or they kept me low, face down in handcuffs.”

“Since I was considered high-risk, they had me in isolation for two months. During that time I was kept incommunicado, I was not allowed to have telephone calls. I was also prevented from communicating with the other prisoners. After two months they returned me to the general population. I felt as though I’d regained my freedom, because the other prisoners treated me well and I was allowed to use the telephone once every 15 days. II could also write letters, although that was limited since I was only allowed two pages and four postage stamps.”

As he speaks he uncovers his wrists to show the scars that remain. He reaches out to grab a document from the shelf, a copy of the injunction his lawyers filed against his transfer from the medium-security prison in Oaxaca and then to El Altiplano, Almoloya, in the state of Mexico.

Among his memories of incarceration, Gonzalo Molina relives the torture he experienced at the hands of federal police, and the hunger strike he undertook in El Altiplano to demand his transfer to the prison in Chilpancingo.

“When I decided to go on the hunger strike, I asked the other prisoners to support me. The support I asked for was that they not provide me with food, nothing, because if I was found with food it would undermine my struggle.”

“And did they give you with the help you requested?” the reporter asks.

“Yes, they provided me with a lot of support, which was what kept me going to continue my fight.”

In the other corner of the cell, Molina’s wife, Ausencia Honorato Vazquez, sits silently.. She has visited him since he arrived in prison in Chilpancingo on June 7, 2015.

In the midst of the conversation, Molina recalls, “When I was in the general prison population in Oaxaca, I could go out on the patio for two hours every five days and one hour on the sports field every 15 days. I was in jail there for 6 months. After that, they transferred me to El Altiplano, where I stayed for 14 months. The treatment there was very different: they let me paint, write and exercise; and the food was better. I could also make a 10-minute phone calls every nine days.”

The conversation with Gonzalo changes tone as his memories become more painful. The room fills with silence. Not even the buzzing of a fly is noticed. But when there are happy stories, everyone laughs freely.

Who’s on the inside, who’s on the outside

When I spoke with Gonzalo in his prison cell, fewer than 24 hours had passed since the escape of the most wanted man in Mexico and the United States: Joaquin Guzman Loera (El Chapo). A week before, Molina had invited me to speak to him in prison through a family member. I arrived with student from the nearby Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College an Ayotzinapa Normal School student, Jose Angel Sanchez Madero, at noon. There, following paperwork and physical inspection by a guard, we were allowed to enter, but not before they took the copy of Proceso magazine and the book, Operación mascare, by Rodolfo Walsh, which we had brought for the political prisoner.

We met Gonzalo in Conjugal Unit 1, with his wife who was allowed to visit daily to take care of him and monitor the effects of his strike, this time launched to demand the release of all the prisoners from his organization, the Regional Coalition of Communitarian Authorities (CRAC, by its Spanish initials). The obligatory question regarded the escape of El Chapo Guzmán.

“El Chapo did not escape on his own. He must have escaped with the help of individuals inside and outside the prison, because it isn’t easy to find a way out with all the existing security measures,” Molina states.

I pitch another question: “Gonzalo, you were locked up with the most-wanted narcos in Mexico, how did they treat you?”

“As far as I’m concerned, they always treated me with respect, even though I was with the heads of the most dangerous cartels in the country. When I spoke with them, I explained our system of community justice and that in our community territory we want peace and tranquility. They viewed that positively.”

After speaking about the narcos and the violence in Guerrero, we return to our conversation about the system of social reintegration that the State has implemented to contain organized crime, but which has not resolved anything.

Gonzalo says, “There is no reintegration. The system of reintegration will never compare with our form of re-education of the people. Here, those who are imprisoned come out with more hatred toward society because they don’t interact with others, everyone sticks to their own. It simply won’t work that way.”

From there, Molina jumps into a discussion of his imprisonment. “My incarceration has been a strategy by the government to eliminate the House of Justice we established in El Paraiso. They believed that their political and economic interests, along with their relationships with narco traffickers, were at risk due so that’s why they threw me in jail. The government began to realize that its interests were at risk; for that reason they invented charges of federal crimes to isolate us from our families.”

__________________________________________________________________

The government began to realize that its interests were at risk; for that reason they invented federal charges to isolate us

__________________________________________________________________

He adds: “The truth is there is no crime in what we did. We simply exercised our rights to free self-determination recognized in Law 701, Article 2 of the Constitution and Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). They continue to hold us here [in prison] because of that, because they are still scared.”

“Gonzalo, do you trust the Mexican penal system?” I ask.

“No, that’s why we are denouncing the judges and magistrates, and they don’t really have any other option but to let us go because everyone knows that in Mexico they incarcerate, murder, persecute and disappear people, just like the Rural Teaching College students from Ayotzinapa. As that case has made clear, the government is the one that kills.”

The community system of justice

Gonzalo Molina maintains that their system of indigenous justice is legally valid and must be respected. He goes on to explain the value of indigenous community institutions as an example for the rest of the country.

“Our proof includes: the constitutive documents of our assembly, the appointments and agreements of the assembly.. The courts cannot justify our incarceration,” he says.

“They think that the Regional Coalition of Communitarian Authorities (is a Civil Association when in fact we are an institution recognized by the communities, which gives us much broader legitimacy.

He continues to explain that by carrying out the procuration of justice in the indigenous system he has committed no crime. “None of their accusations against me are backed up by evidence. There has been no crime to follow-up on. We simply want the government to respect our institution. We just want the government to respect us.”

The community system of justice that Gonzalo’s talking about is the system that the indigenous communities have been recovering to build their autonomy. It is made up of a governing council, commissaries, and community police, who are all elected in the community assembly.

Before Gonzalo was incarcerated, he knew there were several warrants for his arrest, but the warrants didn’t stop him because that would have been tantamount to accepting government demands and admitting guilt to the charges they laid against him.

“I knew there were warrants for my arrest, but for that very reason I didn’t hide. We wanted to demonstrate to the government that we weren’t operating outside of the legal framework. In fact, a day before I was taken into custody, I was at an event in the municipal government seat, to receive a fellow community member who was being released,” he notes.

Gonzalo tells me he writes letters to other members of the community police who have been incarcerated. “We have rights that must be exercised. That’s why we are fighting, so that they respect our community institutions. We are standing with our fellow community police members Nestora [Salgado] and Arturo [Campos]..* We write letters to them for the love of our community. Being in jail does not break us. Just the opposite–it reaffirms our conviction, because we are certain that our system of re-education is security and justice.”

__________________________________________________________________

We are fighting so that they respect our community institutions. __________________________________________________________________

“Do you hold any anger towards the former governor, Angel Aguirre?” I squeeze Gonzalo with another question.

“No, because the struggle isn’t against Aguirre. He is part of the system, but I don’t even hold resentment toward those who accused me.”

“Those who accused me are the same people who have relationships with the highest powers within a corrupted system. The State’s judicial system is rotten, there is a dominant class that maintains control,” he states.

“Would you re-educate the former governor Aguirre?” I ask.

“Yes. In fact, if the people register a complaint to the community justice system against Angel Aguirre, of course, he would be re-educated in the manner of our system of indigenous justice, so that tomorrow he’ll be a good person and not cause more of the same damage.”

Kau Sirenio Pioquinto is a journalist who works with a variety of news media in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, such as El Sur, La Jornada Guerrero, Semanario Trinchera and Radio y Television de Guerrero. He is a contributor to the CIP Americas Program https://www.americas.org/es/

Editor: Laura Carlsen

Translation: Erin Jonasson

* Other members of CRAC held as political prisoners