NOTE: This article is the third in a series by the CIP TransBorder Project that examines the water crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Sonorenses take pride in their prominent role in forging Mexico. Four of Mexico’s post-revolutionary presidents were born in Sonora, including General Álvaro Obregón. Sonorans also boast how they have defeated the climate and created a new Sonora in the historically uninhabited desert landscapes of western Sonora – with the exceptions of the Seris who made their homes along the coast and the Tohono O’odam, a people who for centuries have scraped out a living in center of the Sonoran Desert.

Mexicans from other states commonly regard Sonoran pride – an attitude associated largely with the state’s elite – with disdain, regarding it as arrogance and a sense of superiority. In part, this criticism reflects a resentment and distrust related to Sonora’s historical connections and proximity to the United States. In part, too, Sonorans are generally taller and have more European features than elsewhere in Mexico.

But Sonora has another reputation – one more grounded in the state’s mountain west than in the desert east. Typically, residents of the Western Sierra Madre, Sonora’s land of mountains and narrow river valleys, boast of their independence and ruggedness.

For intellectuals based in Mexico City in the early 20th century, the frontier territories of Sonora and Chihuahua were barbarous places, worlds apart from the more cultured society of Mexico City. When you enter a discussion about their state, you might hear Sonorans from La Sierra jokingly observe: “La civilización termina donde comienza la carne asada.” It’s a quote from the famous Mexican writer José Vasconcelos, who spent part of his childhood in Sonora, and roughly translates as, “Civilization ends where grilled meat begins.”[1]

The mining town of Cananea reflected the brave and barbarous currents in Sonora during the brutal regime of Porfírio Díaz, whose decades-long regime fell to the revolution. It was the 1906 miners’ strike in the U.S.-owned Cananea copper mine that sparked the popular struggle against the hated Porfirio Diaz regime (1876-1910).

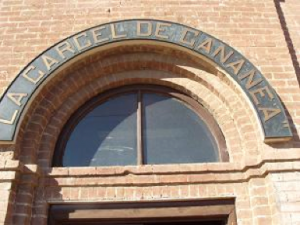

“La cárcel de Cananea,” (“Jail of Cananea”) is one of Mexico’s most famous corridos, a ballad about a down-on-his luck Sonoran who is put in the clinker in Cananea–the jail where striking miners were locked up in 1906. Despite the jail’s central place in Mexican history and culture – it’s now a Worker’s Museum – this isn’t a part of the state’s history that is often mentioned by the government or Sonoran elite.

“La cárcel de Cananea,” (“Jail of Cananea”) is one of Mexico’s most famous corridos, a ballad about a down-on-his luck Sonoran who is put in the clinker in Cananea–the jail where striking miners were locked up in 1906. Despite the jail’s central place in Mexican history and culture – it’s now a Worker’s Museum – this isn’t a part of the state’s history that is often mentioned by the government or Sonoran elite.

Linda Ronstadt’s version on her “Canciones de mi padre” (“Songs of my father”) kept the corrido alive both in Mexico and in the United States. Ronstadt’s father and family hail from Banámichi, one of the villages hardest hit by the August 6, 2014 spill of 40,000 cubic meters of sulfuric acid from the Cananea copper mine into the Sonora River by Grupo México, the country’ largest mining company.

The Sonora SI

Governor Guillermo Padrés established the Sonora SI in 2010 to ramp up the state’s hydraulic infrastructure with a new package of water megaprojects, including an aqueduct to transfer water from the Yaqui River to the badly depleted Sonora River basin.

“Sonora SI, System Integral, is the largest infrastructure and engineering program in the history of our state,” the agency states. Sonora SI asserts that its water megaprojects program is “intelligent and visionary – and sustainable.”[2]

For many critics of Governor Padrés, his promises to create “A New Sonora” – the slogan of his six-year administration – is less a sign of Sonoran confidence and pride, and more a manifestation of the arrogance of Sonora’s white and mestizo elite and their separate reality.[3]

A scion of an elite family in Hermosillo, Padrés wasn’t a well-known figure nationally or in Sonora before his 2009 campaign for governor. As the standard bearer of PAN (National Action Party), Padrés won the mid-2009 election contest mostly because Sonorans had grown weary of Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), particularly in the state capital of Hermosillo.

Sonora was largely a one-party state before the 2009 election. Although the PRI lost control of the state congress in 1997, the party kept the governorship under its control and the PRI’s dominance in Sonora continued long after PAN won control on the national level. Mexico was a one-party nation before the 1997 congressional elections when PRI lost control of the national congress for the first time and the 2000 presidential election when PAN’s Vicente Fox won the presidency.

Padrés’ victory ended a string of 22 PRI governorships. PRI figures have occupied the governor’s office since1929 – the year that the PRI was born and became Mexico’s ruling party.

Padrés succeeded a discredited and disgraced PRI government in Sonora. Many blamed the PRI government for the ABC Guardería tragedy in June 2009 (a month before the gubernatorial election) when 49 infants and toddlers died in a suspicious fire.[4] Intra-PRI disputes sent the ruling party’s approval rates plummeting.

Padrés succeeded a discredited and disgraced PRI government in Sonora. Many blamed the PRI government for the ABC Guardería tragedy in June 2009 (a month before the gubernatorial election) when 49 infants and toddlers died in a suspicious fire.[4] Intra-PRI disputes sent the ruling party’s approval rates plummeting.

Mexican presidents and governors, limited to six-year terms, often launch showy infrastructure programs as a strategy to distribute favors and to establish their own legacies. From the start, Padrés linked his administration to the ambitious program of water megaprojects – Sonora SI (Integral System of Infrastructure Projects).[5]

Since the mid-1980s Sonorans – from the urban poor of Hermosillo to the wealthy agribusiness and industrial magnates –have become increasingly alarmed about the rapidly escalating water crises besieging the state. Leading political and business figures had for three decades been proposing projects and schemes to address the pressing problems of urban water shortages, the salinization of irrigated coastal plains, and lack of water-treatment plants even in large cities. There was even broad support for a scheme to meet Sonora’s water needs by constructing an aqueduct that would allow water from the states of Sinaloa and Nayarit to flow north to Sonora.

But a combination of factors — political party discord, competing proposals, and the high costs of desalinization plants, new dams, and aqueducts — stifled progress in addressing the state’s water crises through new hydraulic infrastructure.[6] Despite cross-party support for many of these waterworks, inter-party politics was also a likely factor in stalling proposed water megaprojects.

For Padrés the political stars were fortuitously aligned in 2009. Padrés won the governorship when President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) ruled the country from Los Pinos, the presidential mansion in Mexico City. From the launch of SONORA SI in 2010, Padrés counted on the highly vocal and active support of President Calderón. The Calderón administration cooperated in fast-tracking permits and impact studies for Sonora SI’s megaprojects, especially for its three priorities: 1) the Independencia or Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct, 2) the Bicentenario or Pilares dam, and 3) the Revolución aqueduct.

The Independencia aqueduct (completed except for last segment called the Franja Norte) brings Yaqui River water to Hermosillo; the Bicentenario project (under construction) would be the second dam on the Mayo River, increasing irrigated agriculture in the river’s upper basin, and 3) the Revolución aqueduct (near completion) would bring water to the cities of southern Sonora and increase agricultural development in the Mayo River Valley.

The contamination of the Sonora River and the discovery that the governor had illegally built dams and reservoirs on his family’s ranch in the Sonora River basin (on a tributary to the east not affected by the contamination) has cast a shadow on the governor’s promise of a New Sonora.[7] Even those in favor of the aqueduct regarded the state government’s arrest and incarceration of leaders of the Yaqui opposition to the Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct as a blatant violation of the governor’s oft-repeated commitment to enforce the rule of law in Sonora. Tomás Rojo, a Yaqui leader and spokesman for various Yaqui governors, told me: “We are solely demanding that our traditional water rights be respected, and we, unlike Governor Padrés, stand on the side of the law.”

Moreover, a series of revelations about the increased state debt and missing state revenues earned the government the nickname of “Goberladrón” (Governor Thief) among his critics, including an informal nonpartisan movement of dissidents that call themselves the “Malnacidos” (literally the “born bad” ones) – a taunting critique of Sonora’s elite and an implicit tribute to Sonora’s less-privileged classes.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] See blog “Ciudad Obregón en Sonora,” Aug, 29, 2010, at: http://obson.wordpress.com/2010/08/29/la-civilizacion-termina-donde-comienza-la-carne-asada/

[2] See Sonora Sistema Integral (Sonora SI), at: http://sonorasi.mx/web/

[3] See, for example, the continuing coverage of the Padrés administration in Dossiér Político.com and Sonora SI

[4] Will Grant, “Guardería ABC: la tragedia que México no olvida y que “puede ocurrir de Nuevo,” June 5, 2014, BBC Mundo, at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/noticias/2014/06/140603_mexico_quinto_aniversario_guarderia_abc_jcps.shtml

[5] “Decreto qe crea un Organismo Público Descentralizado Denominado ‘Fondo de Operación de Obras Sonora SI,’” 3 de junio de 2010, at: http://sonorasi.mx/descargas/Decreto_de_Creacion_Fondo_Sonora_SI.pdf

[6] Pineda Pablos, N. (2007). Construcciones y demoliciones. Participación social y deliberación públicaen los proyectos del acueducto de El Novillo y de la planta desaladora de Hermosillo 1994-2001. Región y Sociedad, XIX(Especial), 89-115.

[7] “Enfrenta gobernador de Sonora 3 procesos por presa: Conagua.” Atando Cabos, Nov. 25, 2014, at: http://www.radioformula.com.mx/notas.asp?Idn=458593&idFC=2014#sthash.vG1BHGgD.dpuf

Photos: Tom Barrry

All articles in this 13-part series:

1. The Yaqui Water War

https://www.americas.org/archives/13463

2. Sonora and Arizona’s Uncertain Water Futures

https://www.americas.org/archives/13485

3. The Illusions of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/13852

4. Sonora Launches Controversial Megaprojects in Response to Water Crisis

https://www.americas.org/archives/13854

5. Origins and Disappearance of the Yaqui River

https://www.americas.org/archives/13892

6. The Old and New Sonoras: The Context for Sonora’s Water Wars

https://www.americas.org/archives/14008

7. Making the Desert Bloom: The Rise of Sonora’s Hydraulic Society

https://www.americas.org/archives/14017

8. The Damming of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/14025

9. Mining Boom in the Sierra Madre

https://www.americas.org/archives/14040

10. Mexico’s Three Mining Giants

https://www.americas.org/archives/14044

11. Mining Water in Sonora: Grupo México’s “Irregular” Water Permits in the Sonora, Yaqui, and San Pedro River Basins

https://www.americas.org/archives/13998

12. Making Mining Dreams Come True in Mexico

https://www.americas.org/archives/14055

13. Mining, Megaprojects, and Metrosexuals in Sonora