Rodolfo Stavenhagen, an intellectual author of the United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed by the UN General Assembly in 2007 after 21 years of negotiations, died Nov. 7. His contributions to anthropology and sociology were highly respected throughout Latin and North America. He served as the first Indigenous Rights Rapporteur for the United Nations Human Rights Council from 2001–2008.

Rodolfo Stavenhagen, an intellectual author of the United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed by the UN General Assembly in 2007 after 21 years of negotiations, died Nov. 7. His contributions to anthropology and sociology were highly respected throughout Latin and North America. He served as the first Indigenous Rights Rapporteur for the United Nations Human Rights Council from 2001–2008.

Another person also died on Nov 7. Described as an anonymous indigenous Yaqui, he was killed at Loma de Bacum in Yaqui Territory. The Yaqui nation has a history of one of the most intense historical and ongoing resistance movements against the entrenched interests of investors backed by the state of Sonora and the Federal Government of México.

The anonymous Yaqui was killed defending the same rights that Stavenhagen diligently worked for at the UN. Stavenhagen attempted to set out a working relationship between the United Nations Human Rights Council and its member states, including the United States and Mexico, –to protect indigenous peoples and lands against the greed of energy and mining companies.

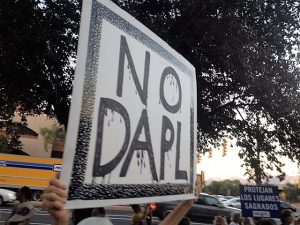

The conflict over water in Loma de Bacum took a life and wounded eight. The Yaqui movement echos the organization of indigenous peoples today, from the Lakota and Dakota at Standing Rock all the way to the Mapuche at Temuco, Chile. The huge protests of water defenders at Standing Rock, North Dakota in defense of the Hunkpapa Lakota and Yanktonai Dakota homeland against a 3.7 billionn (USD) gas pipeline project that threatens their water source, the Missouri River has been the focal point lately.

The Yaqui River at Loma de Bacum, Mexico was the site of an earlier struggle to divert water from indigenous territory for use in the capital of Hermosillo, Sonora. The state of Sonora sanctioned the construction of an aqueduct in 2013-2014. It is now threatened again by a gas pipeline under construction. Yoeme community members defended their water and lands against the Independence Aqueduct, a project of former Sonoran Governor Guillermo Padrés, blocking the highway to commercial traffic and in the courts. The arrest and imprisonment of a leader, Mario Luna, provoked international protests including a statement from Amnesty International calling for impartial justice.

The gas pipeline project originated in the United States, passed through the Tohono O’odham Nation over the Arizona border into Sonora, Mexico in 2015. It is designed to end in Sinaloa, Mexico, the state south of Sonora. Cyanide leaching from a mine owned by the mining company Grupo Mexico, already critically polluted the Yaqui River was upstream in Northern Sonora in August of 2013. Former governor Padrés, now charged with fraud and money-laundering, strongly promoted the Grupo Mexico mine.

The basic principle at the core of demands of indigenous peoples at Standing Rock and at Loma de Bacum has been supported internationally by two former UN Special Rapporteurs for Indigenous Rights, and recently endorsed by the current Rapporteur, Victoria Tauli Corpus from the Philippines. That principle states that governments must ensure that companies consult with indigenous peoples prior to launching megaprojects and was first set out in the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Articles 26 and 27:

Article 26

- Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or other – wise used or acquired.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.

- States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned.

Article 27

States shall establish and implement, in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned, a fair, independent, impartial, open and transparent process, giving due recognition to indigenous peoples’ laws, traditions, customs and land tenure systems, to recognize and adjudicate the rights of indigenous peoples pertaining to their lands, territories and resources, including those which were traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used. Indigenous peoples shall have the right to participate in this process

James Anaya, the second UN Rapporteur for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples from 2008–2014 and an Apache, another indigenous nation with a long history of resistance, spent six years focusing his UN mandate on constructing protocols for UN Member States to use as guideposts for consulting with indigenous peoples prior to approving of extractive industries’ projects in indigenous lands. The 2007 Declaration clearly did not give absolute sovereignty to indigenous peoples, otherwise they would be eligible as member-states in the UN system. However, Anaya’s past efforts and the ongoing contributions of his former staff established protocols to be used in both reforming constitutional articles for the protection of indigenous rights, such as occurred in Colombia (despite the war that targeted indigenous populations), and has been used in legal cases defending indigenous land rights in Nicaragua, Belize and among the Sami in Northern European countries of Norway and Sweden. After Stavenhagen completed the first consultation with Mexico, other indigenous nations requested similar visits to discuss prior consultation. Among them were Argentina, Colombia, Belize and the United States. This work nevertheless has not yet deterred Mexico nor the United States from ignoring the principle of prior consultation with indigenous peoples.

The clamor for indigenous rights at Standing Rock reflects a simmering international issue underlying the future of neoliberal governments’ energy policy. The numerous protests at Standing Rock hardly elicited national media attention in September or October during the he-said she-said presidential election frenzy, despite the longevity of the protests, and the cost of the natural resources involved. But as Navajo protester Liz Mackenzie stated in September,

People are finally noticing us, not as beings of the past, not as, like, costumes you buy in Halloween stores. Like, we are here, we are still fighting, and that does mean a lot.

Despite the Paris COP 21 Climate summit goal of lower global carbon energy sources, neoliberal energy policy is allied with energy companies in a race to lock in carbon and uranium based energy sources worldwide. That policy priority is being tested politically by indigenous protests up and down the continent of the Americas.

As Stavenhagen taught, in the body politic of the Americas, alliances between indigenous and working class allies were the probable path to national democratic development. But despite the UN’s Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) launching a fact-finding mission about abuses of indigenous rights at Standing Rock, Stavenhagen’s thesis is being sorely tested by the environmental racism demonstrated at Loma de Bacum and Standing Rock. In 2015 the Paris Climate agreement stated that the UN collectively,

Recognizes the need to strengthen knowledge, technologies, practices and efforts of local communities and indigenous peoples related to addressing and responding to climate change, and establishes a platform for the exchange of experiences and sharing of best practices on mitigation and adaptation in a holistic and integrated manner (V. Non-Party Stakeholders, para 135)

And it confirmed their,

Agreeing to uphold and promote regional and international cooperation in order to mobilize stronger and more ambitious climate action by all Parties and non-Party stakeholders, including civil society, the private sector, financial institutions, cities and other subnational authorities, local communities and indigenous peoples. (Preamble).

Despite the highly parsed language about “sharing best practices on mitigation”, the U.S. and Mexican governments consistently act in favor of neoliberal development and in disregard of the Paris Climate Agreement’s main goal to reduce carbon emissions. Indigenous actions at Standing Rock and at Loma de Bacum point to a retrenchment for carbon-based energy extracted from or traversed through indigenous homelands that threaten indigenous riverine environments. Global reserves of unrecovered shale gas continue to be confirmed, as oil major states and multinational companies invest in extraction operations, pipeline, storage and export facilities. The top producers in order of the largest reserves are North America (US, Canada, and Mexico), China, Argentina, Algeria, South Africa, Russia, Brazil, Australia and the UAE.

At stake is whether energy companies and the political class can get away with using the old colonial killing fields for the “new” energy business.

Blake Gentry (Cherokee) works as a public policy and development adviser to the nation of O’odham in Sonora, Mexico, and as a consultant on climate adaptation for rural and indigenous peoples and a contributor to the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org