It was the largest and the boldest Women’s Day march in the history of Mexico City. Tens of thousands of women pulsed through the downtown streets, a river of violet mirrored by the jacaranda trees in full spring bloom. Women of all ages, sectors, classes, barrios, schools and political and sexual orientation marched; they filled the streets with their bodies and their cries. The relatively few men present marched at the end or on the sidelines.

It was the largest and the boldest Women’s Day march in the history of Mexico City. Tens of thousands of women pulsed through the downtown streets, a river of violet mirrored by the jacaranda trees in full spring bloom. Women of all ages, sectors, classes, barrios, schools and political and sexual orientation marched; they filled the streets with their bodies and their cries. The relatively few men present marched at the end or on the sidelines.

The march that departed from the city’s Monument to the Revolution brought together housewives who had never before demonstrated for anything, feminists who participate every March 8th, women who have survived violence and women who fear they will be next. A terrible shared experience unites their lives and their rage: violence against women. It isn’t an abstract issue for anyone–every woman there has intimate knowledge of gender violence, whether from suffering violence in her own body or against a sister, a mother, a daughter or a close friend.

Why are women so angry?

Few issues have generated so much polemic in so little time as Mexican women’s protests this year. Social networks buzzed with attacks on feminism and on the women who dared to raise their voices and take to the streets. ‘What right do they have to complain, if things are changing under a progressive government that’s on their side?’, many argued, as if the rising number of femicides were merely an atavism of a bygone era. The sheer number of hate messages against women who publicly demanded their right to live a life free of violence revealed how gender violence forms part of a structure of male privilege that refuses to give way even amid other changesin society.

As feminist demonstrations in Mexico grew in size and militancy over the past few years building up to this year’s historic march, many politicians and ommentarists have asked the rhetorical question: ‘Why are women so angry?’

The women themselves reply:

“The authorities have done nothing in over a year,” Vania explained when asked why she decided to march. Vania’s sister-in-law was a victim of femicide on May 24, 2019. “They kidnapped and murdered her and her body appeared in Iztapalapa,” said the young woman who carried the photo of her sister-in-law. For her, marching alongside other women offers some hope of seeing real change. “We hope that the social conscience will change, that there will be a much greater awareness so that the abuse of women will end.”

Further up, two women also marched behind photos of women killed or disappeared. They come from Ecatepec, a city on the outskirts of Mexico City and one of the deadliest places for women in all of Mexico. “Usually I don’t participate,” the oldest of them said, “but today is an important day. I’m the mother of three daughters and every day I get up in the morning and ask God to take care of them. We live on a street just a few blocks from the ‘Ecatepec Monster’ (a serial killer of women finally captured in 2018). I know the neighbor whose daughter was murdered and eaten.”

Further up, two women also marched behind photos of women killed or disappeared. They come from Ecatepec, a city on the outskirts of Mexico City and one of the deadliest places for women in all of Mexico. “Usually I don’t participate,” the oldest of them said, “but today is an important day. I’m the mother of three daughters and every day I get up in the morning and ask God to take care of them. We live on a street just a few blocks from the ‘Ecatepec Monster’ (a serial killer of women finally captured in 2018). I know the neighbor whose daughter was murdered and eaten.”

She said she can’t even let her youngest daughter, 10 years old, go out to the corner to buy tortillas anymore. The girl looked on solemnly as her mother spoke. “My daughter was attacked, so we’re here to raise our voices.”

Her friend added, “We live in Ecatepec and we’re fed up with so much violence and watching Mexican society continue to rot little by little.”

Thousands of women applauded as the first contingent made up of the mothers of femicide victims set off to lead the huge parade of women. Each mother carried a bouquet of flowers in remembrance of her daughter. Their pain and persistence have granted them indisputable moral authority in Mexico’s growing movement against violence against women.

Irinea Buendía is one of the best-known figures for her struggle for justice dating back a decade. Her daughter, Mariana Lima Buendía, was brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend in 2010 and the assassin and the police tried to pass it off as a suicide. The case went to the Supreme Court and resulted in a decision that requires the State to investigate and prosecute cases with a gender perspective and to provide reparations for human rights violations.

Despite the achievement, Irinea’s fight didn’t end there. A short woman with white hair and an indomitable spirit, she continues to vindicate her daughter’s name and life. “My daughter was killed, she did not commit suicide,” she told the crowd. “This is how the judges and the authorities hide behind their lies; they say that the murderers of women are innocent–they have empathy for them, for the murderers, and not for us. This has to stop! We are here to demand that President López Obrador take a position on femicides.”

Alongside hundreds of mothers of femicide victims, Buendia denounced a recent proposal by the Federal Prosecutor to eliminate the specific criminal classification of femicide and define it as the aggravated homicide of women. Mothers and activists like Irinea, fought long and hard to win recognition of femicide as a separate crime with particular characteristics that causes grave harm to society as a whole.

Fatima Quintana’s mother also marches in the lead contingent. Fatima was 12 years old in February 2015, when “three of my neighbors felt they had the right to take my daughter’s life,” says Lorena Gutierrez. “They tortured her, raped her, and left her half buried. She was just a girl, a girl for whom the government could not even guarantee the safety to go to school and return home alive.”

“The state owes a debt to Fatima and to all the murdered women and girls in the country.”

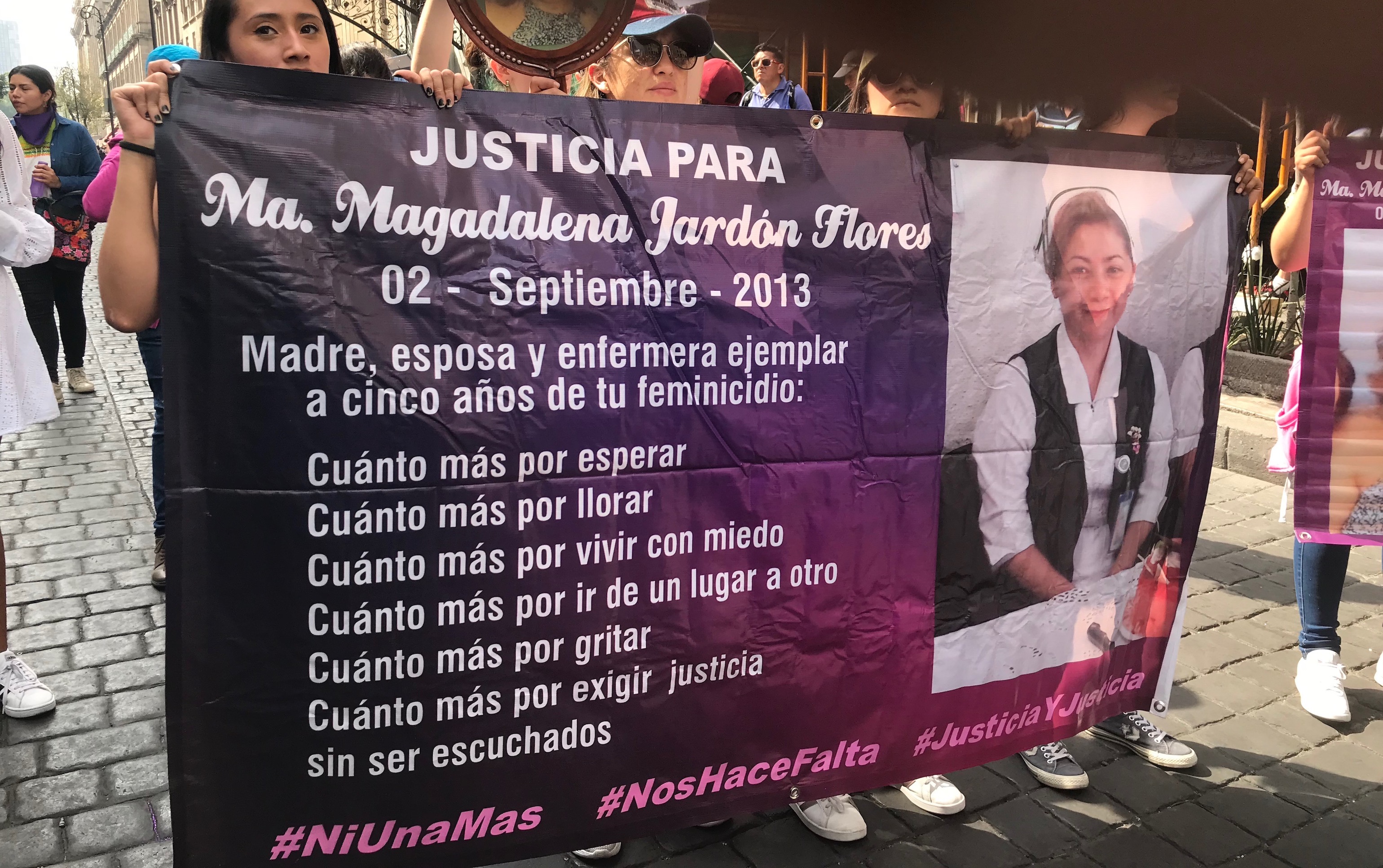

The first contingent arrived at the central plaza when thousands more still lined up to leave the Monument to the Revolution. Along the entire route, the streets were full of women. Entering the downtown square ringed by the Cathedral, the National Palace and other government buildings, the relatives of María Magdalena Jardón marched together behind a canvas with a color photo of the victim. Mag da, a nurse at a public hospital, left work one night in 2013. They found her body a few days later.

da, a nurse at a public hospital, left work one night in 2013. They found her body a few days later.

“We haven’t received any answers from the government. They always say there is not enough evidence to arrest anyone,” said her niece, Claudia Jardón. “We have sought justice for seven years, we have knocked on doors and nobody has opened to us. We’re here to make government and society aware of our pain. When you experience it firsthand, it kills a part of you. They not only killed Magda, they killed us as a family,” Claudia said with tears in her eyes.

The central plaza hosts scenarios of feminist rebellion. On one side, women broke through the barrier in front of the Cathedral and took the stage set up there for another event to unfurl a purple banner: “Fight back today to not die tomorrow”. Others sit picnic-style on the cement square over the painted names of victims. At the National Palace, a small group challenges the police defense line.

As women file out of the square, a young woman stood statue-like in the middle of the main avenue, 20 de Noviembre. “I am a feminist because I was raped,” read a hand-written sign folded at her feet. “Yes, that’s me,” said the woman in her twenties. Her voice cracked with a mixture of pain and defiance. It is the first time she had ever introduced herself that way.

The unity of diversities

Mexico City’s historic march united women who had never met, but who immediately recognized each other. Women from the LGBTQ community, youth, anarchists, actors, artists and music, students, sex workers, women with disabilities, NGOs, came together along with many more groups that had been organizing for years or that had organized specifically to march together this year.

“This is a way of making our struggle visible,” said Tania Marcela from her wheelchair. “Our contingent includes women who are deaf, and have mental and physical disabilities. We are at a disadvantage and even more so as women.”

Work-related violence presents other kinds of threats and violence for women on the job. Women workers from a broad range of service and production sectors participate to denounce discrimination, and the threat of losing their jobs as a form of blackmail in which the male supervisors ask the workers for “favors”. Women journalists marched behind a canvas that read: “For them to publish your articles, you don’t need to go out with the editor.”

Work-related violence presents other kinds of threats and violence for women on the job. Women workers from a broad range of service and production sectors participate to denounce discrimination, and the threat of losing their jobs as a form of blackmail in which the male supervisors ask the workers for “favors”. Women journalists marched behind a canvas that read: “For them to publish your articles, you don’t need to go out with the editor.”

“We experience inequalities, injustices and harassment that are very normalized in the newsrooms,” said Reina Paz of La Crónica. “We’re here to speak out against that situation that we usually have to confront alone, even if it’s just with our small signs.”

Youth organized on an unprecedented level for this year’s International Women’s Day march, some in groups that been working on women’s rights for years and others spontaneously. One group of young women came together through WhatsApp to march together for strength and security and ended up with 130 members. Each wears a white ribbon tied around her left wrist. “We thought it was necessary to come out today to show that we’re not afraid and that we want to continue living,” says Sabrina Quevedo, 23. “It has affected us because in our closest circles, several friends have disappeared these days and it’s not right.”

The section of mothers with their children also occupied a protected position at the front of the march. “I’ve marched all my life, but today I couldn’t miss it – for them and for me,” said Gabriela Salinas Parra, pointing to her 12-year-old son, Rodrigo Perez Salinas. “I think it’s important that he listen to the rage that we women have because to change this system, men have to become aware and it is difficult when they’re adults.” Her son adds: “I realized how important women in the country are when I marched last year and after hearing about the cases [of femicides] in January and February I decided I had to come to support women because if we don’t, we’re basically lost.”

A group of students from elementary to high school who go to Colegio Madrid joined by some of their mothers assembled at the Monument. A young woman from the high school explained, “We were at school talking about how to participate and we decided to all come, because of all the impunity we women suffer and how statistics are rising and there’s no government response.”

She asked not to publish her name, saying ‘I speak for all of our collective’ as her colleagues nodded in agreement, and explained that it was important for them that this be an action only for women. “I think creating a separatist contingent is fundamental, because although men want to participate in the movement, they can’t. It’s our struggle and they don’t suffer what we do.” The young women around her end in a chorus of “Not one less!”

Something shifted profoundly in the political life of Mexico this March 8th. The authorities estimated that some 80,000 women marched, while other sources calculated the numbers at more than 100,000. Many different ways of protesting including dance and spray painting and slogans and direct action expressed a collective anger and a single demand to simply live without violence.

Alongside the demands for an end to gender violence another slogan arose repeatedly: “Nothing about us without us.” All politics is about women because we are half the world.

Mexico’s leaders have to understand what the marchers themselves understood–after this International Women’s Day, Mexico can never be the same as it was before. Mexican women will not allow it.