NOTE: This article is the eighth in a series by the CIP TransBorder Project that examines the water crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Like other states in the Transborder West, population growth and economic development and modernization are products of hydraulic manipulations. Damming, diverting, and drilling have turned the Sonoran Desert – which covers nearly 40% of the state — into a green belt for agribusiness and the state’s urban core.

But the achievements of Sonora’s hydraulic society have depleted water basins, turned rivers into dusty riverbeds, and precipitated a rash of social, political, and economic conflicts.

To keep Sonora developing and to satisfying the ever-increasing demands for more water, Governor Guillermo Padrés Elías in 2010 created a new executive branch agency called Sonora SI (Integrated Systems) to supervise the launching new hydraulic projects. With federal funding from Conagua (National Water Commission), Sonora SI promises to complete 24 water projects, including new dams, irrigation canals, deep water wells, and aqueducts.

The goal of the first Sonora SI water megaproject – the Independencia or Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct – was to solve the acute water shortages in Hermosillo, which is the state’s capital and the home of nearly one-third of the state’s population.

Hermosillo residents, construction companies, industries, and agribusiness resoundingly approved of the new aqueduct, which reached the city in late 2013. However, in the lower Yaqui River basin the traditional and current beneficiaries greeted the proposal to transfer water from the Yaqui River with an angry “No.”

The Yaquis soon became the militant vanguard of the “No al Novillo” coalition opposing the construction and operation of the aqueduct. The focus of the anti-aqueduct coalition was the transfer of 75 million cubic meters (75 Mm3) of water from the Yaqui River Basin to the badly depleted Sonora River Basin.

The Yaqui water war has also raised questions about the sustainability of Sonora’s hydraulic society — and about the political viability of new plans to further manipulate the state’s increasingly scarce water supplies.

Sonora Water Facts

- Sonora has 27 major or mid-sized dams – 18 of which are located in the Yaqui River basin, with four on the Concepción River, three on the Sonora River, and two on the Mayo River.

- There are six water basins associated with six rivers: Río Sonoita, Río Concepción, Río Sonora, Río Mátape, Río Yaqui y Río Mayo.

- Annual precipitation: 427 milímetros (national average is 772 mm).

- Fifth driest state (following Baja California Sur, Baja California Norte, Coahuila, and Chihuahua).

- Average annual surface water flows were 5,459 million cubic meters but total annual demand was 5,500 Mm3 – constituting a deficit of 41 Mm3 in 2005.

- Irrigation systems allow the farming of 653,000 hectares of Sonoran arid and semi-arid territory – of which 63% depend on surface water flows and 27% on wells.

Natural and Unnatural Flows

Water flows along the earth’s surface and down arroyos, streams, and rivers into ponds, lakes, and seas. A small percentage of the earth’s precipitation seeps into earth, accumulating over the millennia in aquifers and large water basins.

In the Sonoran Desert and other arid lands, only during extraordinary and extended rain events does the water that falls from heavens penetrate the desert’s crust. Low annual precipitation rates – 4 to 14 inches, depending on which area – don’t fully explain why Sonora has so little water.

Because the desert is so hot and sun-drenched, the high rates of potential evaporation and plant transpiration generally exceed precipitation rates – which is essentially the definition a desert.[i] In other words, most of the water that falls on the Sonoran Desert neither flows nor seeps. Instead, precipitation returns to the skies in the form of vapor.

Without water, there is no life. That’s a truism that echoes throughout the arid lands of the Transborder West. In any conversation about scarce water resources in the Chihuahuan or Sonoran Deserts, there is some participant who invariably observes: “Aqua es vida” — or some English or Spanish variation of this experienced wisdom.

Before the current era of fuel and electric pumps, most human settlements were found next to or near natural sources of water. Yet, because of the fluid quality of water, human settlements and civilizations have extended their geographic reach by channeling water from distant rivers, lakes, and springs. Canals and aqueducts made life possible in some of the world’s most arid zones by creating reliable supplies of water for irrigation and domestic consumption.

Most ancient civilizations depended on water engineering or hydraulics. Even when communities lived near rivers, in arid regions, river flows were not dependable, necessitating the construction of aqueducts that brought water to population centers from higher elevations.

Such was the case, for example, for the Paquimé culture, which reached its height in the 15th century shortly before the Spanish arrived. Situated near the headwaters of the Casas Grandes River in what is now Chihuahua, the society could not have survived without a network of gravity-fed channels and reservoirs transferring water from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental into the center of the Paquimé society. These channels and cisterns remain today as evidence of the ingenuity of the Paquimé culture.

In Sonora, some indigenous communities (notably Opata and Pima Bajo) had river-fed irrigation system. Others (Yaquis and Mayos) relied solely on floodplain farming before the Spanish Conquest. Begging in the first half the 17th century, the Jesuit missionaries set about improving and extending indigenous irrigation practices, which, along with Jesuit-mandated indigenous farm labor, greatly increased agricultural production.

By the late 1800s the hydraulics of commercial agriculture in Sonora no longer depended on gravity alone. Pump-fed irrigation canals opened up new agricultural frontiers, transferring river water to desert scrublands.

Still, there are natural limits imposed on modern hydraulic systems. Energy-driven hydraulic systems, like those that fed the network of canals in the foreign-owned irrigation districts of the Yaqui Valley during the last two decades of the 19th century and first four decades of the 20th century, were still limited by the variations in river flows. During the autumn and spring dry seasons, there simply wasn’t enough water flowing in the Yaqui River to transfer into the newly cleared irrigation-dependent fields.

Foreign agribusiness companies such as the Richardson Construction Company in the Yaqui Valley started pressuring the Mexican government in the late 1800s and early 1900s to dam the Yaqui River. Only by damming the river could the company realize its plans to extend irrigation canals beyond the delta and throughout the entire semi-arid coastal plain.

Reacting to this pressure and animated by its own modernization ambitions, the post-revolutionary Mexican government launched an ambitious modernization program in the 1920s that included the planned construction of an array of hydraulic infrastructure projects.

Mexico closely followed the development model already well underway in the U.S. West. Under the auspices of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (the bureaucratic manifestation of the U.S. Reclamation Act of 1902), the U.S. government open the largely arid Western states to agricultural and urban development by constructing dams, reservoirs, and long-distance irrigation canals, thereby enabling the transfer of river water across the desert. The rapidly growing hydraulic society of the U.S. West also served as Mexico’s model for the subsidized electrification of the desert cities and irrigation districts of Sonora and elsewhere.

During the administration of President Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-28), the government promulgated the Ley de Irrigación con Aguas Federales (Federal Water Law) that committed the federal government to develop major irrigation projects based on federally constructed dams, irrigation canals, and hydroelectric plants. In 1926 President Elías Calles established the National Irrigation Commission to implement this agricultural development and modernization plan.[ii]

Post-revolutionary political turmoil delayed the construction of the planned hydraulic infrastructure. Not until the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) did Mexico have the stability and political leadership necessary to embark on program of economic nationalism and modernization. In 1936 President Cárdenas, closely following the early proposals of the Richardson Construction Company, ordered the construction of Sonora’s first dam.

Modeled after the Boulder (Hoover) Dam on the Colorado River, the federal government with U.S. financing completed La Angostura dam and reservoir in the upper Yaqui River basin in 1942. Baptized the Lázaro Cárdenas dam, Sonora’s first water megaproject blocked the natural flow of Bavispe River – the largest northern tributary of the Yaqui River – as it entered the narrow canyon known as La Angostura.

Carrying within its banks more than two-thirds of Sonora’s surface water, the Yaqui River Basin extends south from the river’s headwaters in southeastern Arizona to the coastal plains in southwestern Sonora. Blocking the natural flow of the river, the new dam and reservoir controlled the release of river water, thereby enabling irrigation in the Yaqui Valley even during the dry months.

Yaqui River Basin Facts

- Carrying within its banks more than two-thirds of Sonora’s surface water, the Yaqui River Basin extends south from the river’s headwaters in southeastern Arizona to the coastal plains in southwestern Sonora.

- By far the largest (encompassing 71,452 km2 and healthiest in Sonora, with annual river flows from tributaries and river averaging 2,852 Mm3 (measured mid-basin at the Novillo / Álvaro Obregón dam).

- Yaqui River basin accounts for 69% of all the surface water in Conagua’s Noroeste region (covering virtually all of Sonora and a bit of northwest Chihuahua).

- Yaqui RIver dams/reservoirs: Lázaro Cárdenas (La Angostura); Álvaro Obregón (El Novillo); and Plutarco Elías Calles (Oviáchic), finished, respectively, in 1942, 1952, and 1965.

- There is no public registry of water users and water rights in the basin, pointing the failure of the federal and state governments to formulate plans for the sustainable use of its waters.

- Principal water users of basin water in order of usage: Yaqui Valley Irrigation District (41), Ciudad Obregón, Grupo de México (La Caridad mine), Colonias Yaqui Irrigation District (018), and small farmers and ranchers who live along the upper and middle basins. Another major

- No official or unofficial assessment exists of the quantity of groundwater in the lower Yaqui River basin, although damming the river dried up the delta and virtually ended the recharge of the valley’s aquifers by the river.

- Nor is there any comprehensive assessment of the quality of groundwater in the Yaqui Valley, although tests of water wells do reveal severe contamination (mostly by agrochemicals).

The federal government assumed control of the Richardson Construction Company (CCR) and its network of irrigation canals, while also redistributing private and public lands into collectively owned ejidos throughout the Yaqui Valley and giving the Yaqui people ownership of some 425,000 acres in the Yaqui Valley and in the Mátape Valley to the north.

The Richardson Brothers and other agribusiness investors in the Yaqui Valley had long recognized that only by damming the flow of the Yaqui River could their farming enterprises count on regular flows of water.

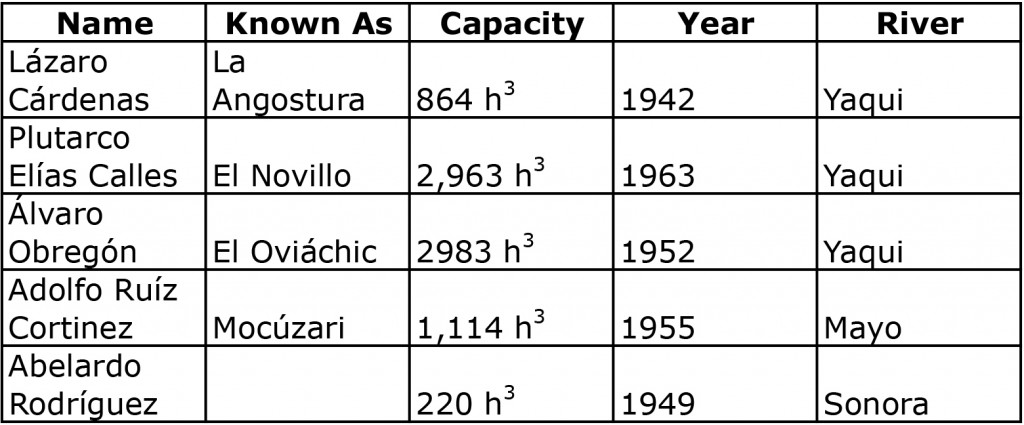

La Angostura, which was completed in 1942, was the first of three major dams on the Yaqui River. Soon after its completion, the farmers of the Yaqui Valley Irrigation District were clamoring for a larger dam that would be built at the start of the lower Yaqui River basin.

To further control flooding during major rain events and to ensure an even more dependable supply of irrigation water for the Yaqui Valley, two other larger dams were later constructed: El Novillo and El Oviáchic, the former 145 kilometers to west of Hermosillo and the latter 35 kilometers northeast of Cd. Obregón.

With El Novillo and Oviáchic dams in place by 1962, it became readily apparent that La Angostura, the first and the smallest of these water megaprojects, had become redundant – although the copper mine in Nacozari had become dependent on water from the reservoir. Although three dams were built with hydroelectric plants, only the generating plant at the El Novillo dam still regularly generates electricity.

Sonora’s Largest Reservoirs

Conversion: 1 hm3 = 1000000 m3

Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara, one of the most respected analysts of Mexico’s agricultural sector, described in her history of Mexican agriculture how Sonora, largely owing the creation of hydraulic society starting in the 1940s, became known as the “Mesopotamia of Mexico” and the “Agricultural Cornucopia of Mexico.”[i]

Since the early 1940s Sonora’s demographic and agricultural boom has been largely the product of hydraulic manipulation. Despite its aridness, Sonora is Mexico’s second largest agricultural producer — virtually all the result of irrigation.

By the 1960s, one-fourth of federal spending for irrigation infrastructure had gone to Sonora. As a result, irrigated land in Sonora nearly doubled in two decades.[ii] Eleven percent Sonora’s land is irrigated, making it the state with highest percent of its agricultural land served by irrigation systems[iii]

No other state in Mexico has been so dramatically transformed by the federal government’s network of dams, aqueducts, and irrigation canals. Agriculture accounts for 92.3% of water consumption in Sonora,[iv] and no other Mexican state is intensively irrigated as Sonora. Virtually all this agriculture occurs in the arid western plains and along the coast, where average annual rainfall is 4-15 inches, depending on the part of the state – with the most precipitation in the Sierra Madre Occidental and the least in the Altar Desert in northwest Sonora.

Solving Water Shortages with More Hydraulic Megaprojects

Throughout Mexico, government entities – at the local, state, and federal levels – have again been calling for new water megaprojects to address the country’s acute water shortages. Sonora – the state that disproportionately benefited from Mexico’s hydraulic infrastructure projects – is leading the way to a new hydraulic future with its Sonora SI (Sistema Integral) program.

Elected in July 2009, Governor Padrés can rightly claim to be leading Sonora’s hydraulic renovation. Shortly after he received the governor’s sash and moved into the Palacio del Gobierno, Padrés declared that he would create “Un Nuevo Sonora” during his six-year term (sexenio). With its plan for 22 hydraulic megaprojects, Sonora SI is the designated flagship program of the governor’s “Nuevo Sonora.”

As the Sonoran government — with more than two-thirds financing from the federal government — continues with its water megaproject program, there is little reflection of the failures and consequences of Sonora’s “hydraulic society.”

Instead most of those involved in the water wars in Sonora — with the exception of small circles of environmentalists and academics — look to inter-state and intra-state aqueducts, along with proposed desalinization plants to solve the intensifying water crisis.

Both sides of the Yaqui water war, for example, support an unimplemented federal plan for an aqueduct that would bring water from the Nayarit and southern Sinaloa (two water-rich states along the Pacific coast) to Sonora. The Northwest Hydraulic Plan (PHLINO) would be a mega-megaproject that would transfer water to the Sonoran Desert and the semi-arid region of northern Sinaloa – areas that receive 5-20% of the precipitation that falls in the tropical state of Nayarit. [v]

In pointing to the PHLINO inter-state aqueduct as the ultimate solution to Sonora’s water crisis, proponents ignore concerns by environmentalists that such a massive inter-regional transfer of water would further diminish the state’s already decimated rainforests.

Similarly, despite the indigenous rights component of the Yaqui water war, calls for the PHLINO have not considered the opinions of the Wixárika (Huichol) and other indigenous communities native to Sinaloa, whose land is under siege by water-hungry mining companies.[vi]

The anti-Independencia coalition, then, is not opposed to water megaprojects. They just don’t want the megaprojects built for the Yaqui Valley to be tapped by other interests.

The valley’s agricultural sector, its agro-industries (including the highly polluting chicken and pork sectors), and the wealth of Ciudad Obregón are the products of Sonora’s first water megaprojects, including the network of irrigation canals dating from the early 1900s, the three Yaqui River dams and reservoirs, and the large irrigation canal – named in honor of Lázaro Cárdenas — that channels water from the Oviáchic reservoir directly to the Yaqui Valley.

Because of these megaprojects, Sonora’s largest river no longer flows to the sea. The river delta is a remnant of the pre-dam era, when the Yaqui River would flood part of the valley. The valley’s groundwater basin is also a remnant of a time when the river ran free.

As is, the Yaquis receive very little of the water stored in any of the three reservoirs on the Yaqui River. Virtually all the water that flows to the valley through canals goes to agribusiness and to white or mestizo farmers who either own large extensions of valley land or rent Yaqui land

Before the government dammed the Yaqui River, the once mighty river reached the coastal plain where the Yaquis live. Water seeped through the alluvium left in the floodplains. Over the millennia, the delta created aquifers of fossil water, recharged year after year as the river flowed to the sea.

Agribusinesses, agro-industries, and the city of Obregón tap this groundwater, supplementing the water supplies channeled from the Oviáchic reservoir. Persuaded by government promises that Yaqui communities would receive potable water, the Yaquis agreed in 1991 to allow the state government and Conagua to construct an aqueduct to transfer this fossil water to the desert cities to the north.

A battery of pumps feeds this Yaqui-Guaymas aqueduct that delivers water to purification plants serving Guaymas, Empalme, and San Carlos. But the government only partially complied with its promises to supply the Yaquis with drinking water. In large part, this deception explains Yaqui opposition to yet another

Shutting down the Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct wouldn’t mean that the Yaqui River start flowing through the Yaqui Valley. Nor would it necessarily mean that Yaquis would reclaim their heritage as farmers. Turning off the flow of water to Hermosillo wouldn’t help recharge the shrinking and now badly contaminated aquifers of the Yaqui delta region. A victory by the No al Novillo coalition wouldn’t result in better access to drinking water for the Yaquis.

The transfer of water from the Yaqui River basin to Hermosillo will, however, make it still more difficult for the Yaquis to pursue their historic claims to water from the Yaqui River. With as much as 75 Mm3 of Yaqui River water flowing annually to Hermosillo, the Yaquis face yet another obstacle in pursuing demands that the federal government honor the tribe’s water rights. The now vested interests of Hermosillo in having access to the Yaqui River will likely prove much stronger than the historic water rights of the Yaquis.

Hydraulic megaprojects have reshaped and redefined Sonora. Without hydraulics, there would be no New Sonora.

The Yaqui Valley wouldn’t be Mexico’s breadbox, the population of Hermosillo would not have tripled over the past three decades, Ford wouldn’t have opened a major manufacturing plant in Hermosillo, San Carlos would not now be a booming vacation spot, and the Nacozari copper mining operations would not have the water it needed to expand on such a massive scale.

Yet, from the beginning, modern hydraulic projects have had heavy costs and consequences. The dams and reservoirs on the Yaqui, Mayo, and Sonora Rivers have each displaced hundreds of families. Most were subsistence farmers with indigenous roots – few of whom were adequately compensated for their losses. Reservoir water now covers many villages of the Old Sonora. [vii]

Even farmers who are able to remain in dammed river basins are adversely. As reservoirs capture river water, not only do farmers suffer from reduced river flows in many areas but they also see groundwater levels drop, forcing them either to drill deeper or abandon their farms. Among the dozens of Yaqui River communities most affected by reduced access to surface and groundwater, Granados and Huásabas stand out both because of the extent of their water losses and because the State Water Commission and Conagua claimed in 2011 that these farmers had sold their water rights, thereby increasing the amount of unallocated river water and permitting the transfer of this water to Hermosillo through the Independencia aqueduct.

The environmental costs of Sonora’s hydraulics society have never been calculated, just as the environmental impacts of Sonora SI’s new projects – dams, aqueducts, reservoirs, and a proposed desalinization plant – have been glossed over in declarations about role of these projects in purportedly solving the Sonora’s deepening water crisis.[viii]

[i] Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara, La modernización de la agricultura mexicana, 1940-1970 (Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 1978)

[ii] Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara, La modernización de la agricultura mexicana, 1940-1970 (Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 1978), p. 131; Cited in Evans, Damming Sonora, p.6.

[iii] Refugio I. Rochin, “Mexico’s Agriculture Crisis: A Study of its Northern States,” Mexican Studies 1, 1985, p. 257; Gary Paul Nabhan and Andrew R. Goldsmith, “State of the Sonoran Desert Biome: Uniqueness, Biodiversity, Threats, and the Adequacy of Protection in the Sonoran Bioregion, ” p. 34, cited by Evans, p. 6.

[iv] Análisis sobre el uso y manejo de los recursos hidráulicos en el estado fronterizo de Sonora, Comisión Estatal de Agua (CEA), Octubre 2005.

[v] El Plan Hidrauico del Noroeste, Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua and Semarnat, at: https://www.imta.gob.mx/historico/instituto/historial-proyectoswrp/rd/2009/fi-rd0821-3.pdf

[vi] “The Huichol (Wixárika) People’s fight against multinational mining companies,” Geo-Mexico, Nov. 14, 2014, at: http://geo-mexico.com/?p=12177

[vii] In “Damming Sonora,” Evans recounts the tragic case of the community of Casa de Teras community that was forcibly relocated to the Yaqui Valley to make way for La Angostura reservoir. This process of dislocation starting with La Angostura in the late 1930 was repeated in the construction of the other major dams in the state into the early 1960s. Even small dams like El Molinito (completed in 1991) on the Sonora River displaced stable communities of small farmers and ejidatarios. See, for example: Rolando E. Díaz Caravantes and Ernesto Camou Healy, “El agua e Sonora: tan cerca y tan lejos. Estudio de caso del ejido Molino de Camou,” Región y Sociedad, No. 34, 2005.

[viii] Sustainability in the Yaqui Valley, A project of Center for Environmental Science and Policy, Stanford Institute for International Studies, Stanford University, at: http://yaquivalley.stanford.edu/; Margaret Reeves, “Yaqui Fields of Poison,” PAN North America, Summer 2006.

[i] “The Sonora Desert: Background Information,” Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, 2007.

[ii] Sterling Evans, “Damming Sonora: An Environmental and Transnational History of Water, Agriculture, and Society in Northwest Mexico,” Produced for Workshop in the History of Agriculture and Environment, University of Georgia, March 25, 2011; Robert C. West, Sonora Its Geographic Personality (Austin: University of Texas, 1993).

All articles in this 13-part series:

1. The Yaqui Water War

https://www.americas.org/archives/13463

2. Sonora and Arizona’s Uncertain Water Futures

https://www.americas.org/archives/13485

3. The Illusions of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/13852

4. Sonora Launches Controversial Megaprojects in Response to Water Crisis

https://www.americas.org/archives/13854

5. Origins and Disappearance of the Yaqui River

https://www.americas.org/archives/13892

6. The Old and New Sonoras: The Context for Sonora’s Water Wars

https://www.americas.org/archives/14008

7. Making the Desert Bloom: The Rise of Sonora’s Hydraulic Society

https://www.americas.org/archives/14017

8. The Damming of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/14025

9. Mining Boom in the Sierra Madre

https://www.americas.org/archives/14040

10. Mexico’s Three Mining Giants

https://www.americas.org/archives/14044

11. Mining Water in Sonora: Grupo México’s “Irregular” Water Permits in the Sonora, Yaqui, and San Pedro River Basins

https://www.americas.org/archives/13998

12. Making Mining Dreams Come True in Mexico

https://www.americas.org/archives/14055

13. Mining, Megaprojects, and Metrosexuals in Sonora