In celebrating sustainable food systems, World Food Day is recognizing the need for systemic change to end hunger and malnutrition. Systemic change is urgent because even though for decades the world has produced 1 ½ times enough food for every man, woman and child on the planet, nearly a billion people go hungry while over a billion are malnourished. Ironically, most of the hungry are the very ones producing half the world’s food: peasant women. Similarly, most of the food insecure people in the developed world are food and farm workers—as are many of those suffering from obesity and diet-related disease.

In celebrating sustainable food systems, World Food Day is recognizing the need for systemic change to end hunger and malnutrition. Systemic change is urgent because even though for decades the world has produced 1 ½ times enough food for every man, woman and child on the planet, nearly a billion people go hungry while over a billion are malnourished. Ironically, most of the hungry are the very ones producing half the world’s food: peasant women. Similarly, most of the food insecure people in the developed world are food and farm workers—as are many of those suffering from obesity and diet-related disease.

Hunger and malnutrition are not by-products, but an integral part of the global food system. Ensuring environmental sustainability, food security and good nutrition around the world—as the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) asserts—will require a radical transformation in how we grow our food.

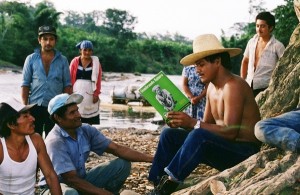

Luckily, we have many examples of sustainable food systems in the making. Agroecologically-managed smallholder farms like Latin America’s Campesino a Campesino Movement increase yields, conserve soil, water, and biodiversity and capture carbon to cool the planet. Urban farms from Havana to Bangkok are steadily increasing food production and improving livelihoods. Community-supported Agriculture groups around the world provide fresh, healthy food for members and a living income for local family farmers. Hundreds of municipal Food Policy Councils and Food Hubs are implementing citizen-driven initiatives to keep the food dollar in the community where it can recycle up to five times, thereby creating jobs and kick-starting local economic development. What do all these efforts have in common? They are grounded in sustainable, equitable and dignified livelihoods.

We know what practices make a food system sustainable. Why don’t we enact enabling policies to prioritize them? The simple answer is that the institutions that produce the agreements, laws and regulations shaping our food systems don’t yet have the political will to make sustainable food systems a priority, and they are still a long way from addressing the structural changes needed for food system transformation. Historically, the political will for systems change responds to practice, awareness and the power of strong social movements.

The movements for food sovereignty, food justice, agroecology, climate justice, women’s rights and labor rights are spreading, and their influence on our food system is growing. As the food, fuel, climate and financial crises worsen, these movements are steadily converging—in all their diversity—into a force to be reckoned with. Their impact is felt in the United Nation’s Committee on World Food Security (CFS)—the “most inclusive international and intergovernmental platform for all stakeholders to work together in a coordinated way to ensure food security and nutrition for all.” La Vía Campesina, the international peasant movement that defends 2 million small-scale food producers champions Food Sovereignty, the democratization of the world’s food systems in favor of women and the poor.

In the United States, Europe, Africa and Latin America, food sovereignty alliances have formed, bringing together producers, environmentalists, consumers and indigenous organizations to forge new policies and institutions for sustainable food systems. The power of its social movements led Kerala, India to implement a statewide transition to organic agriculture to protect the environment, ensure food security and provide a dignified livelihood to its farmers. These developments and many others indicate that the catalyst for sustainable food systems—political action—is already in the making.

Eric Holt-Gimenez is the Executive Director of Food First, and a contributor to the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org