The expansion of rights seen in almost all of Latin America is being challenged by the growth of police and institutional repression. From Mexico and Guatemala to Argentina and Brazil, repressive forces are out of control.

The expansion of rights seen in almost all of Latin America is being challenged by the growth of police and institutional repression. From Mexico and Guatemala to Argentina and Brazil, repressive forces are out of control.

“Violent police practices are inconsistent with a rights expansion policy” is the title of a report by the Center for Social and Legal Studies (Centro de Estudios Sociales y Legales, CELS), chaired by Horacio Verbitsky. [1] The report highlights “serious acts of institutional violence” in several Buenos Aires neighborhoods, as well as “violence in jails and police stations” and the return of the repression of social protest.

In its analysis, CELS exposes “the lack of a structural reform of the security system”, in the case of Argentina, centered on “street control”. He sites the need for public debate on “what a democratic security system should be.” Argentina can serve as an example of the deterioration of human rights throughout the region, with the most critical expressions in Mexico and Guatemala.

These violations are not random or occasional in a continent undergoing increasing militarization and paramilitarization of everyday life. In Uruguay, the erosion of human rights is expressed in the torture of youth detained for minor offenses.[2] In Brazil, the massacre of favela residents has become systematic, as revealed by the Maes de Maio, who recorded at least one slaughter per year since 1990– under democracy.[3] In Mexico and Guatemala, the assassination of indigenous people, women, and the poor are commonplace. The media often attribute the killings to drug traffickers or occasional outbursts of security forces. But this explanation seems insufficient. Or, worse, it covers up the reality.

Argentina exemplifies the deterioration of recent years for two reasons. First because there are independent human rights organizations that, since the end of dictatorship in 1984, have carefully recorded state and institutional violations. Second, because the Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez governments have pledged to defend human rights since 2003, denouncing violations and avoiding repression.

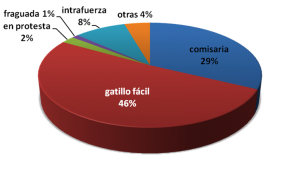

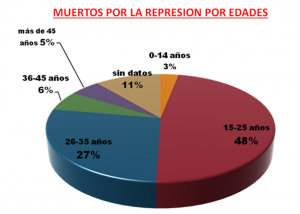

A report by the Coalition Against Police and Institutional Repression (Coordinadora Contra la Represión Policial e Institucional, Correpi) titled “A privileged society sustained by repression,” refers to the cases of gatillo fácil (“trigger-happy” police murders), deaths in jails and police holding cells, and victims of repression of protest. Up to November of last year, there were 4,011 people killed. 47% were between 15 and 25 years old, and 27% between 26 and 35 (see graphs).[4]

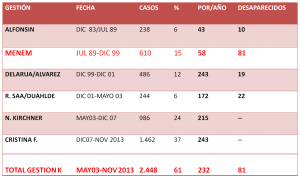

But most symptomatic, and disturbing, part of the report is the chart of police killings over time. In the ten years of the Carlos Menem administration (1989-1999), police killed an average of 58 people each year. His government was savagely neoliberal, privatized all state enterprises, delivering–mostly giving them away–to foreign companies. It was a government repressive against the people. But in the ten years of Kirchner and Fernández (2003-2013), an average of 232 people died at the hadns of the police a year– four times as many (see chart). Yet these governments took human rights seriously, sent a portion of the police leadership into retirement for corruption, and pledged to avoid repression, based on what the CELS calls the “political control” of security forces.

Deaths by repression by age

Notwithstanding, a regression–spanning the last decade–has taken place. This trend cannot be attributed to cyclical issues, the mismanagement of a ministry, or an occasional retreat from state to military control.

Instead, three crucial reasons explain this involution, which transcends Argentina and, with nuances and differences, applies to all of Latin America. First, the socio-economic model; second, the autonomy of repressive apparatuses; and third, fear of popular sector protest.

The current period has been defined as an economy of accumulation by dispossession or plundering that naturally relies on institutional and non-institutional violence. Stealing from people and stealing from nature can only be done by violence. The objective is the obliteration of entire communities to appropriate nature and convert it into commodities, as has been denounced by Subcomandante Marcos in his text “Fourth World War”. “The Fourth World War is destroying humanity as globalization is universalizing the market, and everything human that opposes the logic of the market is an enemy and must be destroyed. In this sense, we are all the enemy to be vanquished: indigenous, non-indigenous, human rights observers, teachers, intellectuals, artists.”[5]

Unlike what happens with accumulation by dispossession in urban and middle class zones (generally privatization), for sectors that have never been socially included or benefited from “welfare,” the extractive model works to conquer territories, destroy enemies, and administer conquered space, subordinating them to capital. Indigenous, black, and mestizo peoples, peasant farmers, poor women, and unemployed, informal workers and children in urban peripheries suffer this type of dispossession.

Admin. Date Cases % per/yr Disappeared

In indigenous/black/mestizo Latin America, the primary modes of discipline have historically not been the panopticon nor the satanic mill, but massacre or threat of massacre (read: extermination), whether under colonial rule or during the Republican periods; in dictatorships and democracies; through to today. The Maes de Maio organization was created by the mothers of the 500 killed in repressive acts in São Paulo in May 2006. The organization states that between 1990 and 2012, there were 25 killings of favela residents–young, black and poor.

This reality has much to do with the extractive model, but also with the type of state that has been constructed in the region. The Latin American nation-state differs from the European nation-state, as Aníbal Quijano reminds us. Here, the democratization of a society that could be expressed in a democratic state wasn’t registered; social relations were fixed on the colonial structure of power established on the idea of race. This became the basic factor in the construction of the nation state, as Quijano continues to point out.

The current production model deepens these elements of colonial rule: the division of our countries into “zones of being” and “zones of non-being.” In the latter, lives don’t count, and repression is not occasional, but the norm. And to assert their rights, citizens cannot go to a state institution, but instead rise and rebel, as is clearly shown by what happened in Mexico after the disappearance of 43 students from a teaching college in Ayotzinapa.

A police state

The right kind of state for this “Fourth World War” is a state that is weak in the face of transnational companies and strong against popular sectors. In parallel, there is a breakdown of the state: it doesn’t include poor sectors in development, but offers them social policies. The police have become autonomous from the state, but functional to a minimum state in the face of capital, and maximum in the face of social protest.

In December 2013, there was a police strike in Argentina’s Córdoba province. The officers withdrew to their barracks, leaving the streets empty and outbursts of criminal violence affected community members. The police force “liberated zones for looting to occur in different districts of the capital,” “according to CELS. The organization stated that what happened in Córdoba was “a threat to governance.” Correpi called them “police riots”, with an “eminently mafia character, like the intended ‘plunders’ parallel to the barracks.” [6]

Save a few exceptions, governments cede to police strikes so as not to be seen as destabilized. In some cases [the strikes] demand wage increases, which are usually rejected when formulated by public sector unions. In others, as in the city of Olavarría in Buenos Aires province, [police] pressured to prevent the courts from ruling against officers accused of abuses and murders. “The lack of political control over the police is a structural problem that leads to security forces becoming autonomous and sustaining discriminatory practices and rights violations,” as CELS argues in its report.

Social struggle and autonomy

There is a close relationship between repression and protest cycles. For Correpi, “preventive repression” is always directed against the poorest, often those who most need to assert their rights. CELS highlights “a serious regression in modes of political management of social conflict” as a result of police action in the occupation of the Pope Francis district, an area occupied by some 700 families on the outskirts of Buenos Aires.

The first increase in repression in Argentina took place in 1989, when social protest raged under hyperinflation. The second was the result of picketing against the effects of deindustrialization, particularly following the uprisings of December 19 and 20, 2001. After that, the spike in repression did not return to previous levels. In the Pope Francis case, CELS asserts that the police and the judiciary sector criminalized community members, prohibiting them from entering the district and “weakened community organization, favoring the retention of criminal gangs.” In this case and others, repressive forces established tacit alliances with organized crime against popular movements.

University of Córdoba activists have called it a police state– formally legal, but dedicated to generating exceptions as a pretext for government repression to stave off “the dangerous classes.” Actions include a wide range of interventions, from “corporate social responsibility policies” that guarantee tax evasion, to police/military intervention aimed toward armed territorial control, where the police force is responsible for administering and managing affairs and bodies in an exclusive and excluding way.[7]

There is, then, a formal extension of rights, but simultaneously the intensification of repression. What is up for debate is the extent to which states can be relied on as guardians of rights. This was the question raised at the XI Human Rights Forum, held at the Universidad Iberoamericana de Puebla, Mexico in October.

Various groups and analysts stressed the importance of autonomy as a form of self-protection, after confirming that one cannot have rights without the power to make them respected. Autonomy is the path to recover the power of the people that was swindled by a “rights state” which, in fact, either doesn’t work or works against the weakest.

At the meeting, Father Alejandro Solalinde spoke of how his shelter works to protect Central American migrants in their passage through Mexico. The establishment of shelters and counseling services plays a role in collective self-defense.

Women from the United Force for Our Disappeared in Mexico (Fuerza Unida por Nuestros Desaparecidos en México, Fundem), which received the Tata Vasco Prize for the defense of human rights, presented two undeniable facts. First, that under these regimes anyone can be disappeared or have his or her rights violated. Second, that protection, searches, and formal complaints cannot wait for state institutions, but must be carried out by those affected.

Chilean lawyer Roberto Garretón, who served in the Vicariate of Solidarity under the Pinochet dictatorship, said that there are actions that serve to decrease the impact and consequences even under the most ferocious repression. An example is the experience of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina.

Recuperating these experiences and practices of solidarity and mutual support–autonomous from the government at every moment–can be vital to the defense of life. If past experience is a guide, they can be small walls against the force impunity and repression.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] http://www.cels.org.ar/ 30 de agosto de 2014.

[2] Ver http://brecha.com.uy/primera-causa/ 25 de setiembre de 2014.

[3] Ver http://maesdemaio.blogspot.com/2012/02/httpwww.html

[4] Ver Informe Anual en Boletín Informativo N° 705 en http://correpi.lahaine.org/?p=1240

[5] http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/auto/fourth.html

[6] Declaración de Correpi, 9 de diciembre de 2013.

[7] María Ferrero y Sergio Job (2011) “Ciudades made in Manhattan”, en Núñez, Ana y Ciuffolini, María (comp.) Política y territorialidad en tres ciudades argentinas, Bueno Aires, El Colectivo.