Last month Spain’s National Tribunal in Madrid issued arrest orders for seventeen soldiers implicated in the murders of Spanish Jesuit priests and two female collaborators at the José Simeon Cañas UCA University in San Salvador in 1989. The soldiers were all members of the infamous Atlacatl Battalion of the Salvadoran Armed Forces.

Although the orders have been delivered to INTERPOL, in El Salvador the Supreme Court must decide whether or not to go ahead with Spain’s demand to extradite the men. Although since 2015 El Salvador’s Supreme Court has permitted INTERPOL to capture fugitives granted amnesty within the country, the men still have protection under the Salvadoran Law of Amnesty that prohibits the re-opening of cases for crimes that occurred during the civil war of the eighties.

In a recent press conference, Minister of Security and Justice Benito Lara stated that the National Civil Police (PNC) is waiting to receive notification to carry out the soldiers’ arrests. The director of the PNC, Mauricio Ramirez Landaverde, said they were still awaiting official correspondence to act on the capture orders.

The Secretary of Communications for the Presidency of El Salvador, Eugenio Chicas, said on the government’s official channel that the arrest orders will be carried out, but he repeated that the decision on the soldiers’ extradition belongs to the country’s Judicial Branch. “It is legally clear to this government that the orders should be executed. But the rest will depend on the Judicial Branch,” said Chicas.

In an interview granted in Spain to a local Salvadoran newspaper, the defense attorney for the accused military men, Antonio Alberca Perez, said that he has already submitted a motion to have the judge who issued the orders, Eloy Velasco recuse himself for being “partial” since he teaches at a Spanish Jesuit university that is associated with the Company of Jesus.

Alberca Perez stated that Velasco should not have issued the arrest orders because the murder of the priests and the two female collaborators had already been dealt with in El Salvador under the Law of Amnesty and, additionally, because some military men had already been tried for the case in El Salvador. Spain, therefore, has no standing to judge the El Salvador case, the attorney argued.

“The judge is absolutely prejudiced. We have presented the documentation that verifies that Judge Velasco is trying events that happened in a Jesuit university. The judge is not letting us see the case, alleging that the accused have evaded Spanish justice, and that this condition demonstrates our clients do not have a guaranteed right to a defense,” Perez said in the interview with the newspaper.

El Salvador’s Prosecutor for Human Rights, David Morales, responded saying that the Salvadoran authorities should proceed at once to arrest the military people charged by Spain. Morales said also that the Salvadoran government and the PNC had the obligation and the duty to cooperate so that justice prevails in the case of the Jesuit priests’ murders.

The prosecutor went further and warned that the high command in the Salvadoran Armed Forces should not intervene in the arrests. “The fulfillment of international detention orders is obligatory and should be executed immediately by the Salvadoran authorities. War crimes are not subject to statutory limitation, and no State can abstain from bringing them to trial. It is thus invalid to apply any sort of amnesty,” Morales said.

For the representatives of the Central American University (UCA), this is a chance for the Salvadoran authorities to redeem themselves in the case. The Vice-Rector for Social Protection, Omar Soriano, said in a press conference that the Salvadoran authorities had to act in compliance with the law. “This is an opportunity for the judicial system in the country to clean up its act. A few months ago there was an alert issued, and the Supreme Court interpreted it as just an order to locate the men and there were no arrests,” said Soriano.

The Director of the Institute for Human Rights of the UCA (IDHUCA), Janeth Aguilar, affirmed that the government should do its part to have El Salvador execute the arrest orders and for justice to be done in the case of the murdered Jesuit priests. “We hope that the country’s Executive Branch eases the conditions for the extradition of these war criminals.”

The Director of the Institute for Human Rights of the UCA (IDHUCA), Janeth Aguilar, affirmed that the government should do its part to have El Salvador execute the arrest orders and for justice to be done in the case of the murdered Jesuit priests. “We hope that the country’s Executive Branch eases the conditions for the extradition of these war criminals.”

This is not the first time that Velasco has issued an arrest order against the soldiers. In 2011 the men involved in the case took refuge in a military barracks, protected by the high military command and the former government. Then the Salvadoran Supreme Court said that the orders issued could only apply to locating the accused and not to effect their extradition to Spain.

The resolution dictated at that time by Judge Velasco, along with the arrest orders, stated that El Salvador, “in whose territory the events occurred, is obliged to carry out the corresponding hunt by virtue of the international arrest order with the intention of extradition issued by the Spanish State.”

In January 2013, then-presidential candidate and vice-president of the country, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, promised he would seek the derogation of the Amnesty Law, approved after the signing of the Peace Agreements. Nonetheless, when questioned by the national press regarding that promise President Sánchez Cerén has left the matter of derogation of the Amnesty Law in the hands of the Supreme Court.

In January 2015, the magistrate of the Supreme Court, Florentin Melendez, said that the point about the law’s derogation would be handled after that year’s presidential elections, so as not to affect the process. Although the magistrate said the matter was under study and the sentence would be issued after March 2015, to this date there has been no resolution regarding the law.

According to the document on the case at the Central Trial Court #6 of the National Tribunal of Madrid, Spain, to which the Americas Program obtained access, the 17 military personnel, among whom are high officials of the Armed Forces, are accused of eight “terrorist murders that constitute crimes against the [Spanish] State” and “an act of crime against humanity or a violation of human rights.”

The military men wanted by the Spanish justice system are the Salvadoran ex-minister of Defense, Rafael Humberto Larios; the colonel and ex-head of Chiefs of Staff of the Armed Forces, René Emilio Ponce; the general and ex-commandant of the Air Force, Juan Rafael Bustillo; the general and ex-vice minister of Defense, Juan Orlando Zepeda; the colonel and ex-vice minister of Public Security, Inocente Orlando Montano, detained in 2014 in the U.S. for immigration fraud and in process of being extradited to Spain; and the colonel and ex-chief of the First Infantry Brigade, Francisco Elena Fuentes. Also among the accused are the former head of the Infantry and the Atlacatl Battalion José Ricardo Espinosa Guerra; and officers of the Atlacatl Battalion, Gonzalo Guevara Cerritos, Oscar Mariano Amaya Grimaldi, Antonio Ramiro Avalos, Angel Perez Vasquez, Tomas Zarpate Castillo, Jose Alberto Sierra Ascensio, Oscar Alberto Leon Linares, Carlos Camilo Hernandez Barahona, and Rene Yusshi Mendoza Vallecillos.

The accusation also extends to the ex-director of the Military Academy where the officers of the Armed Forces were trained, Guillermo Alfredo Benavides; the ex-head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joaquin Arnoldo Cerna Flores; the ex-director of the National Intelligence Agency, Carlos Mauricio Guzman, and the lieutenant of the National Intelligence Agency, Hector Ulises Cuenca Ocampo.

Judge Velasco issued orders for 17 of the accused, since, according to the document of the National Tribunal, one of the alleged perpetrators figures as a protected witness and has already given his statement in Spain, and another of the accused, Colonel Inocente Montano, has been detained in the U.S. on charges of immigration fraud and is waging a legal fight to avoid being extradited to Spain for the murder of the Spanish priests.

Official documents indicate that in 1990 U.S. Army Major Erick Buckland revealed that a special commission of his country had met with regard to the case and identified Benavides as being responsible for giving the orders to the Atlacatl Battalion to murder the Jesuits. In 1992, officers Mendoza Vallecillos and Hernandez Barahona were sentenced to 30 years in prison for the crime, in a trial that was criticized for irregularities. After 15 months, they were pardoned by President Cristiani.

Among other documents revealed in the trial in Spain identifying the aforementioned officers, there are also the “corrected statements” by the attorney and adviser to the Armed Forces, and now representative to the Salvadoran parliament, Rodolfo Parker, in which any and all implications of the high military command are expunged.

The Jesuits, Enemies of the Military

In the late 1970s, priests and clergy of various orders were becoming targets or objectives of the Salvadoran Armed Forces and of paramilitary groups organized by the country’s extreme right. The hatred against priests, especially the Jesuit congregation, originated in the belief among military officials that Marxists had penetrated the Catholic Church and were plotting to undertake offensive actions in collaboration with the guerrillas.

Records that have survived the Salvadoran civil war speak of some 250 “incidents,” including threats, assaults, expulsions, and murders, of priests and clergy accused of “inciting” peasants against the government and the military regime. The Jesuits, because they espoused Liberation Theology, were especially accused of “poisoning the minds of Salvadoran youth” in the secondary schools and universities where they worked.

The high military command, comprised of a group of officers known as “La Tandona,” blamed the Jesuits for the rise in rebelliousness among the country’s students and intellectuals, and for the guerrilla movement in El Salvador. Ignacio Ellacuria, UCA’s rector, was an outspoken political analyst critical of the war, the government, the Armed Forces and its rule, and of the guerrilla.

The high military command, comprised of a group of officers known as “La Tandona,” blamed the Jesuits for the rise in rebelliousness among the country’s students and intellectuals, and for the guerrilla movement in El Salvador. Ignacio Ellacuria, UCA’s rector, was an outspoken political analyst critical of the war, the government, the Armed Forces and its rule, and of the guerrilla.

Official documents included in the Spanish transcript of the case indicate that, over time Ellacuria acted as a mediator between the guerrilla, the rightist government elected in 1984, and the representatives of the United States Embassy in El Salvador. This was sufficient to convince the military that the priest was “one of the main advisers, consultants, and strategists for the FMLN.”

Ellacuria pressured the government and the guerrilla to enter into dialogue. According to the documents to which the America’s Program had access, Ellacuria convinced then-president Alfredo Cristiani to reform the Armed Forces and to promote changes in the lines of command, which functioned as the country’s informal military dictatorship. That appears to have led to the Jesuit’s death sentence, turning them into public enemy #1 for “La Tandona.”

As of 1980, most of the threats against the UCA were directed especially at Ellacuria. The university campus was placed under siege and searched constantly, as the military targeted the Jesuits and insisted that they were hiding weapons for the guerrilla forces. The attacks and threats progressively increased.

The military used the official radio station to make open threats against the Jesuits, warning the public of the danger these clergymen represented for the country because of their allegedly close links with the guerrilla command and their ideas about Liberation Theology.

Ellacuría utilized UCA’s editorial journal to criticize the country’s social context. “As 1980 closes, the society is poised for total confrontation. The project has exhausted its possibilities, and there is no longer any exit other than civil war,” he wrote then.

The National Tribunal’s judicial transcript regarding the events states that the plan to murder the UCA’s rector and the other priests was hatched as on Nov. 5, 1989 and drawn up by the chiefs of the Salvadoran Armed Forces, but it was not till after November 11, when the guerrilla undertook its final offensive “To the Hilt,” that the military set a date to commit the murders.

The reconstruction of events that occurred during the night of Nov. 16, 1989 at the UCA, aided by eye-witness accounts presented in the case’s complaint, are based on the testimonies of three people who managed to hide that day in buildings adjacent to the Jesuits’ residence, from where with horror they observed everything that happened.

“Ellacuria is One of Those Who Has to Die”

In the case records that are in both the Salvadoran transcript and the Spanish documents, Lieutenant Guillermo Alfredo Benavides said he received the order to kill the Jesuits from a superior: “It’s them or us. They have been bleeding our country and we need to tear them down. Ellacuria is one of them and should die. I don’t want any witnesses… It’s an order and must be obeyed.”

The report of the Truth Commission, composed after the signing of the peace agreements in 1992, says that the plan to murder the Jesuits was completed during a meeting. “The officers remained standing, talking in groups; one of these groups was formed by Colonel René Emilio Ponce, Juan Rafael Bustillo, Francisco Elena Fuentes, Juan Orlando Zepeda, and Inocente Orlando Montano. Ponce called Colonel Guillermo Alfredo Benavides and, in front of the other four officers, ordered him to kill father Ellacuria and not to leave witnesses. He also ordered him to use the Atlacatl Battalion” to commit the crime.

This order was given the afternoon of Nov. 15, and according to the Spanish judicial transcript that reconstructs the events prior to the murders, it was the result “of a discussion, prior planning and authorization, and its execution was begun Nov. 11 with the order to lay siege to the UCA.”

The document also confirms that the Salvadoran Armed Forces set the entire apparatus into motion, including the Commandant of the Armed Forces, the soldiers and the command unit of the Atlacatl Battalion, the soldiers of the Belloso Battalion, the military radio station Radio Cuscatlán, the Presidency’s Civilian Center for National Information, the Operational Complex of the Joint Command, the Psychological Operations of the Joint Command, the Armed Forces’ Press Committee (COPREFA), the National Intelligence Agency, and the Technical Center for Police Instruction (CETIPOL).

Some 300 soldiers surrounded the university. The military’s excuse was based on “having received information that terrorist elements had penetrated in the University… and that they had opened fire on military forces” who were patrolling the area. President Cristiani said publicly that “they had found weapons” and “other proof of terrorist activities” in the UCA.

The documents relate that at about 6:30 p.m. the army began a search at the university because they had information that an indeterminate number of delinquents “had entered the UCA, and that they had to confirm their presence. The Atlacatl command unit left the Military Academy (located a few kilometers from the university) to search the Jesuits’ residence and the Center for Theological Reflection. But the real purpose of the search mission had been to make preparations to kill the Jesuits.”

That same night Rector Ellacuria returned from Spain. On arriving at the campus he became aware of the search and told the soldiers they should return in the morning so that, in the daylight, they could do a better search and could see that nothing was being hidden.

The night before the murders, the soldiers that participated in the mission to murder the Jesuits received new uniforms and combat boots as a reward for the work the high command had assigned them. According to the Truth Commission’s report, that same night the Armed Forces authorized attacks against civilians and union members who supported the guerrilla.

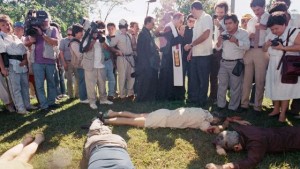

On Nov. 16, more than 200 members of the Armed Forces entered the UCA campus. The objective this time was not to conduct a search, but to murder the Spanish priests Ellacuria, Ignacio Martín Baró, Segundo Montez, Amando Lopez, and Juan Ramón Moreno, and the Salvadoran Joaquin Lopez. The collaborators, Julia Elba Ramos and her daughter Celina Ramos, were trapped at the university by the military-imposed curfew and were murdered to leave no witnesses to the crime.

According to documented information that has not been made public but to which the Americas Program was privy, at about seven in the evening Hernandez Barahona urged the soldiers who would participate in the mission to murder the Jesuits, while the officers of the Armed Forces’ high command met at the Joint Command headquarters to closely follow the operation. At midnight, President Cristiani and some U.S. military advisers joined the meeting.

The soldiers reached the Jesuits’ residence, took them by force out to the garden, and made them lie down on the ground. In the reconstruction of events it was established that Lieutenant Yusshi Mondoza handed over to officer Oscar Mariano Amaya Grimaldi an AK-47 rifle with which to murder the priests, instructing him to make it appear they were members of the FMLN guerrilla.

“The operation was concentrated in three concentric circles: one group remained in the area, another group surrounded the building, and third small select group was chosen to carry out the murders.” The confession of one of the soldiers states that the priests “did not appear to be dangerous. Some were old, they were unarmed and wearing pajamas,” said the soldier.

Amaya Grimaldi began to fire the AK-47 at Ellacuria, Martín Baró, and Montez, who were lying on the ground. The rest of the soldiers killed the other priests. The former chief of the battalion, José Ricardo Espinosa Guerra, who was the only one who covered his face during the operation, said in his statement that, upon seeing the priests on the ground while they were being shot, he turned away with tears in his eyes because he remembered that the priest Segundo Montez had been the principal of the Externado San José school where he had studied as a child.

At the same moment when the shots that killed the Jesuits were heard, Julia Elba and Celina embraced each other as they were being guarded by other soldiers and then were also murdered. The documents assert that the soldier Jorge Alberto Sierra Ascensio received the order to “finish off” the women.

Major Buckland testified later that shots fired from the UCA campus could be heard at the headquarters, where he was sleeping.

Immediately after the killing, some soldiers wrote slogans about the FMLN, so as to make it look like the murderers had been members of the Salvadoran guerrilla.

Carmen Rodriguez is a journalist in San Salvador, El Salvador. She specializes in Security and the Judiciary and has collaborated with the Americas Program since 2014.

Translated by Jonathan Tittler