During the 2016 presidential campaign, progressives who work on U.S. foreign policy issues had high hopes that Bernie Sanders would provide a sharp counterpoint to the hawkish views of Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump. It never happened, in part because his advisors chose to focus on the bread-and-butter economic issues that fueled Sanders’ extraordinary rise to prominence.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, progressives who work on U.S. foreign policy issues had high hopes that Bernie Sanders would provide a sharp counterpoint to the hawkish views of Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump. It never happened, in part because his advisors chose to focus on the bread-and-butter economic issues that fueled Sanders’ extraordinary rise to prominence.

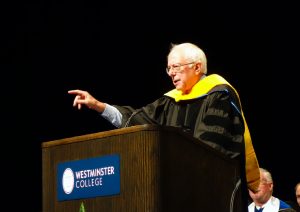

That all changed last week when Sanders gave a speech in Fulton, Missouri, at the same venue where Winston Churchill gave the “Iron Curtain” speech that ushered in the Cold War. Sanders presented the most comprehensive vision of what a progressive U.S. foreign policy should look like of any major U.S. politician in recent memory.

In this era of “fake news” and TV talking heads, the thing that most distinguished the Sanders speech was its sense of history. He noted that past U.S. actions like the U.S.-backed coups in Iran, Guatemala, and Chile had harshly negative consequences that have lasted for decades, not only in terms of the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives at the hands of U.S.-backed dictators but in the transformation of global politics. This was a refreshing change from the usual uncritical rhetoric about America’s role as a leader in the struggle of democracy versus tyranny. It is only by acknowledging America’s actual historical role that a new course can be charted.

And as Donald Trump spouts the rhetoric of war and destruction with respect to North Korea, Sanders reminded us of the value of diplomacy. He contrasted the Iraq war, where hundreds of thousands of lives were lost in a conflict that was originally justified as a hunt for weapons of mass destruction, and the Iran nuclear deal, which rolled back Iran’s nuclear weapons program without a shot being fired or a dollar being spent. And he pointed out that the consequences of the Iraq intervention continue in the actions of ISIS, which would most likely not have been formed absent the U.S. intervention in Iraq.

Sanders also spoke of devastating humanitarian consequences of the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, which has been backed by U.S. arms and logistical support. He was one of 47 Senators who recently voted to block a sale of U.S. bombs to the Saudi regime – a loss, but huge progress from the point just a few years ago when no one in Congress dared to confront the Saudi lobby.

The most unique aspect of the Sanders speech was his focus on global inequality, a glaring phenomenon that is rarely discussed by U.S. politicians. He called out not only the banks and the oil companies, but also U.S. arms companies that have too often used their influence to distort U.S. foreign policy in ways that make war more likely. And he quoted from Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “military-industrial complex” speech, which is more relevant today than when Eisenhower first spoke about it more than 50 years ago.

Sanders speech wasn’t perfect. Most notably, he omitted any reference to Israel or Palestinian rights. But he spoke out on that issue in the 2016 campaign, and hopefully will do so again. He also didn’t stress the importance of U.S. groups building ties with progressive movements in other countries. The U.S. is a global power, and it will require a global movement to shift the U.S. role in the world.

The question now is how to advance the vision that Sanders set out in his speech in Missouri. The first thing that needs to happen is for more of Sanders’ colleagues in Congress to champion the vision and actions that he laid out in his speech. And hopefully the speech will inspire progressive movements in the U.S. to make foreign policy a more central part of their platforms and demands. Stephen Miles of Win Without War, the largest anti-war coalition in the United States and a project of my organization, the Center for International Policy, took to the pages of The Nation to note that Sanders’ speech has finally completed the progressive platform that prompted millions of people to vote for him in 2016.

If the Sanders coalition, joined by vibrant organizations and activists in the immigration and women’s movements and Black Lives Matter, were to unite behind the vision he outlines, a new anti-war, pro-diplomacy, pro-equality movement could grow up in the United States that would rival the peace movement of the 1960s and 1970s. And it can’t come a moment too soon.

William D. Hartung is the director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy and a columnist for Americas Updater/Boletín Américas.