Peaceful Resistance La Puya Celebrates 11 Years of Community Organization in Defense of Territory, Water, and Life, at a critical moment for the future of the organization and its communities. After successfully suspending the Progreso VII Derivada mining project, it now faces a lawsuit of over 400 million dollars filed by the mining company Kappes, Cassiday, and Associates, based in Nevada, USA, against the Guatemalan State. The arbitration is being conducted in a World Bank tribunal that allows foreign companies to sue governments as retaliation against the legitimate defense of their territory and assets by affected communities and national laws.

Peaceful Resistance La Puya Celebrates 11 Years of Community Organization in Defense of Territory, Water, and Life, at a critical moment for the future of the organization and its communities. After successfully suspending the Progreso VII Derivada mining project, it now faces a lawsuit of over 400 million dollars filed by the mining company Kappes, Cassiday, and Associates, based in Nevada, USA, against the Guatemalan State. The arbitration is being conducted in a World Bank tribunal that allows foreign companies to sue governments as retaliation against the legitimate defense of their territory and assets by affected communities and national laws.

In this context, on December 6th, representatives from La Puya and allied organizations gathered to learn about a new study titled “Arbitration as a Pressure Mechanism in the Progreso VII Derivada Project Case,” conducted by Ana Sandoval, an activist of the movement and law student, and to discuss the current situation of the struggle. The study was published by El Observador and can be consulted HERE. La Puya has been a great example worldwide of community resistance against imposed mining in indigenous and peasant territories. Now it is an example of social mobilization to oppose these tribunals, which seek to punish the people for defending themselves against the looting and contamination of their assets to generate profits for transnational companies.

Ana Sandoval, a member of La Puya and a law student, opened the event with a brief history of their struggle. “The resistance began a process in 2012 and from the beginning, it demanded that governmental entities recognize the right to consultation since this consultation should have been carried out before the project began,” she said. This did not happen, and in 2014, the communities filed a legal action requesting the Supreme Court of Justice to recognize the right to prior, free, and informed consultation, enshrined in ILO Convention 169 and Guatemalan laws. In 2016, they won the suspension of the mining company’s exploitation license, and later the definitive amparo. The court’s decision also ordered the consultation to take place.

After losing their case in Guatemalan courts, the company filed a lawsuit against the Guatemalan state for $400 million dollars at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a World Bank institution created under CAFTA. This action led the resistance into an unknown and high-risk battlefield. “It is an exorbitant amount that can significantly affect the budget and, therefore, other rights of all Guatemalans,” Sandoval affirmed.

To face the lawsuit, the Guatemalan government conducted an analysis and hired experts to evaluate the company’s arguments. It was concluded that there is no justification whatsoever for the lawsuit, much less the multimillion-dollar amount demanded by KCA. The State filed a counterclaim against the company for 2 million dollars for the damages that have already been caused.

Sandoval mentioned that now they are waiting to learn the ruling of the arbitration panel handling the process. “These arbitration processes are completely separate from the frameworks of human rights,” she said. She added that it hasn’t been easy to obtain information about the case: “They have tried to exclude the population closest to the project.”

International Arbitration: A Mechanism for Exploitation and Violation of Rights

Jen Moore, a researcher at the Global Economy Program of the Institute for Political Studies, explained that the use of international arbitration claims by transnational corporations, particularly in the extractive sector, was established in the Free Trade Agreements of the 1990s to create a system favorable to the interests of these corporations. The result is a framework of international investment agreements and supranational systems to protect them.

This image illustrates the network of over 2,800 international investment agreements that provide this mechanism for dispute resolution between investors and states.

Moore explained that this dispute resolution system between investors and states is only available to transnational corporations. They can access a tribunal composed of three highly paid lawyers and sue the state not only for the amount invested but also for their speculation on allegedly lost future profits, which can account for up to 80% of the total claim, as in the case of KCA.

In the case of KCA-Guatemala, the communities managed to achieve greater transparency and allow some community representatives to give their testimony, but it is common for directly affected communities to have neither information nor influence in the process. The well-being of the people, their collective rights, and the environment are not considered.

The Regional Map of Mining

Next, Guadalupe Garcia, coordinator of the Observatory of Extractive Industries – an independent research platform that seeks to acquire, organize, and publish data on mining and oil extraction projects in Guatemala – presented a geographical overview of how extractive projects have formed and transformed in the territory, focusing on the region known as the “Golden Belt” where the project is located.

The image shows the main extractive companies with interests in the eastern part of the country. On the right side are the active licenses in red and the applications in yellow. All the licenses in red belong to Mineral de Sierra Pacífico, which now represents the new mining interests that originated from the Progreso VI Derivada project in La Puya. It shows the nickel mining interests in the northeast, particularly in the Izabal Lake basin, and the number of applications that correspond to the global interest in nickel extraction.

Garcia pointed out that the Marlin Mine is located in the west, also part of this conglomerate of projects. Other interests in the west include Reservas del Caribe, a new anonymous society that has numerous applications in the San Marcos and Huehuetenango areas.

In the Golden Belt of El Tambor, the Canadian company Radius currently concentrates all its explorations along the Motagua Fault. This area covers a zone of “epithermal gold” – gold deposits related to hot springs.

Radius acquired all the licenses previously granted to the Tombstone mining company and started making new applications. The El Tambor Mining Project consisted of 12 applications totaling 107,000 hectares.

This table, compiled with information from the Ministry of Energy and Mines, shows the current licenses granted in this area: the licenses updated in January of this year (2022) are marked in red. In this area, the Progreso VII Derivada exploitation license, now suspended, is located, and the exploration licenses are in Santa Margarita, Carlos Antonio, and La Laguna.

If we include the Holly-Banderas area, a new area of mining interest since 2020, we can see that the same actors are using another subsidiary called Minerales Sierra Pacifico to carry out explorations in San Jacinto Chiquimula. It is even known that they have caused fires to eliminate communal forests that are located in an area that is the main water source for Chiquimula. This same company has applications in Sansare, within the indigenous communal area of the communities of Santa Maria Xalapan.

To conclude, the researcher from the Observatory of Extractive Industries presented a diagram of the corporate structure of Radius and how it operates through Volcanic.

Politics and Extraction

Fernando Solis, director of the Civil Association El Observador, analyzed the power relations behind private investment projects in the Golden Belt that began explorations in the first half of the 1990s.

“These were projects that were already there, the existence of veins had been identified, but it was during the government of Jorge Serranos Elias when Guatemala really began to undergo an economic liberalization process,” commented the journalist. He explained that “the origin of all these gold exploration and exploitation projects lies in a transnational group that arrived in Guatemala in 1990 and started negotiating with national capital groups to install investment projects. There is a parent company that will give birth and make agreements with national capital and the government of Alvaro Arzu to start forming this group of licenses.”

He identified at least six economic and political factors that allowed the extractive projects to obtain licenses:

The end of the Internal Armed Conflict and the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996.

The arrival of Alvaro Arzu to the presidency in 1996 and the National Advancement Party (PAN), an openly pro-business government that launched an economic and neoliberal political offensive to attract investments, including the privatization of key strategic services of the State and the expansion of oil and mining operations.

His Minister of Energy and Mines, Engineer Leonel Lopez Rodas, supported the process and later, as President of Congress, promoted a series of reforms to the mining law.

The reform of the Mining Law in 1997 by Arzu, which reduced royalties and opened up investment to transnational companies and capital groups that previously had limited power to intervene in such investments.

Alejandro Sinibaldi from the Patriot Party founded in 2002 was also key, as a congressman between 2008 and 2012 and president of the Legislative Energy and Mines Commission. He promoted a series of initiatives to generate licenses.

The approval of the General Electricity Law in 1996 opened the electricity sector to transnational investments, allowing national and international capital companies to control the sector from generation to transportation, distribution, and commercialization.

Solis pointed out that the main companies that arrived were: Ramon Goldcorp, Intrepid Minerals from Canada, BHP Billiton, Minera Urbana Guatemala, Aurora Gold Corporation, Montana Gold, Tombstone Explorations, Marwest Resources, and Exploration Mayan Minerals. They established the Marlin project, approved in 2003, El Tambor, El Escobal (which is currently undergoing consultation under the ownership of Panamerican Silver), and Cerro Blanco, which had a community consultation on September 18, 2022, in Jutiapa.

To better understand how these interconnected interests operate, Solis explained in detail the functioning of one of them, Marwest, from Montana Exploradora, which operates the Marlin mine. Randy Reifel is the founder of Montana Exploradora and a shareholder in several Canadian mining companies. The main operator of the projects is Simon Ridgway, linked to Volcanic, a new company associated with the previous projects. Another operator is lawyer Jorge Asensio, from the Asensio y Aguirre law firm, and the main operator of the current Mining Law, also serving as the lawyer for the corporate group of Cementos Progreso and the gold extraction projects. Cementos Progreso is the cement monopoly, continued Solis in his presentation, but it is also the main corporate group linked to the mining projects. It is attributed to be one of the groups financing the government and has been funding the strategy against the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) and the criminalization of justice operators, along with 2 or 3 capital groups.

Another group is CMI, Corporacion Multi Inversiones. They are known as the owners of Pollo Campero and owners of one of the largest hydroelectric power plants built to date, Renace. The Campollo Codina Group, owner of the Madre Tierra Sugar Mill, also promotes the extractivist strategy and provides financing to right-wing operations or instances such as the Foundation against Terrorism, linked to NGOs such as Vida Pro Patria and Guatemala Inmortal. There are concrete links between the presence of Cementos Progreso and the other groups in gold investment projects and the right-wing politics that have been deployed since the government of Jimmy Morales and are being deepened during the current government of Giammattei Falla.

Given this constellation of powers, what happens if the arbitration is favorable to the communities of La Puya?

The El Tambor project consists of 11 licenses with a validity of 25 years. If one license is canceled, it does not mean that the projects will end because other licenses can be activated, according to Solis. “Arbitration is a move that KCA is making to recover or compensate for the profits it could have generated; they are speculating with this, with the operation of El Tambor.”

Now, after the Constitutional Court suspended the license and forced the Ministry of Energy and Mines to activate the community consultation, “KCA and the state have not stopped generating interests through the consultation. For example, the Ministry of Energy and Mines is not convening the communities near the project.”

“So there is a game being played by KCA and the state, we believe it’s a two or three-pronged strategy, in the sense that they intend to earn $400 million through an arbitration process, but at the same time, they are thinking that if the consultation takes place, they can isolate the communities that have been part of the resistance and generate a process very similar to what they did in Izabal—a manipulated consultation that convened COCODES (Community Development Councils) that were bought by the same company.

“In summary, the company and the state are anticipating using arbitration alongside the consultation as a process where the company will not lose what it has invested in the El Tambor project so far.”

“In the beginning, the state approached the communities and asked them to intervene and support it in the arbitration process, but it is also playing a two-sided game with the consultation process. This is the situation at the moment, and it’s not only happening in El Tambor, there are other arbitration processes where the state is being sued, for example, in Huehuetenango in the case of the Ixquisis hydroelectric plant in San Mateo. The state has already lost two arbitration processes: with Teco Energy, a company linked to the Campollo Codina group, it had to pay approximately $19 million, and the arbitration process with Trecsa against the state may also be activated.”

The rocky road to consultation

Ana Sandoval added that “despite the fact that Convention 169 establishes that consultation processes must be free, informed, and in accordance with the customs and traditions of each indigenous people, they have been confined to purely Western procedures, and the self-organization of communities is not allowed. This is a very important aspect that is not only happening in the case of La Puya but has also been observed in other consultation processes.”

José Angel Llamas, a member of the Peaceful Resistance La Puya, pointed out that the Ministry of Energy and Mines has tried to restrict the participation of communities in the consultation. “They do not consider us indigenous communities, but we can prove it since we have many deeply rooted customs within our population.” He said that, for example, the Ministry seeks to exclude the La Choleña community, which is located very close to the mine and descends from the Xinca people, from the consultation.

“The Ministry of Energy and Mines has also tried to frustrate several municipalities from sending their representatives,” he said. “That is the concern we have as community members who hope to be respected and allowed to assert that right.”

Llamas points out that even in its early stages, the organization of the consultation presents a series of anomalies – they are not informing the communities about the process and their rights. “It is thanks to the efforts of the communities that we have sought information and are trying to ensure that this awareness is known throughout the population, as the ministry does not provide that opportunity.

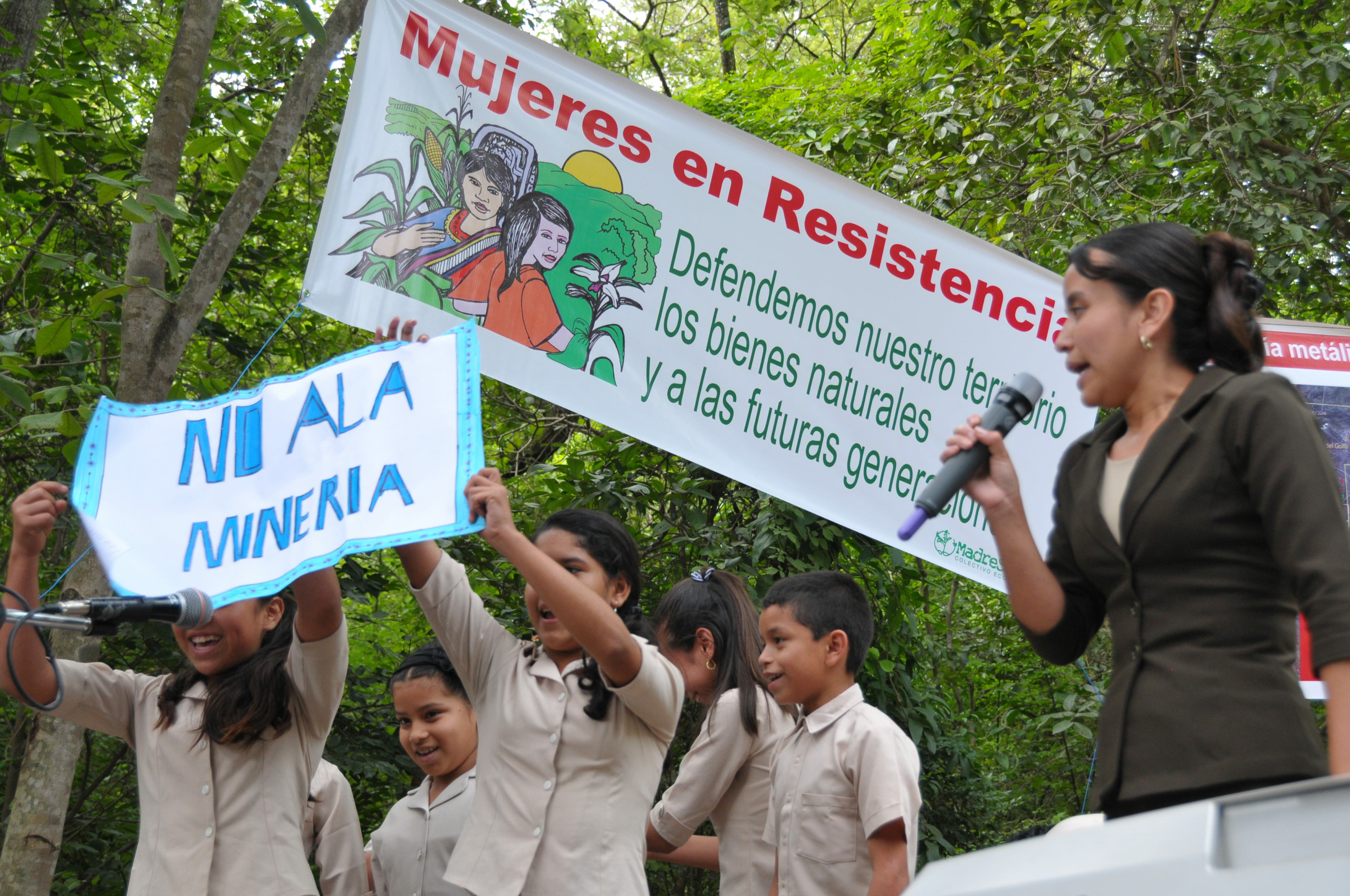

“Despite the difficulties, the event on arbitration and consultation was further proof of the organizational capacity of the Peaceful Resistance La Puya. They managed to socialize information and analysis and publicly denounce violations of their rights, also warning about risks on the horizon. Solidarity was evident in the organization of the event, which was supported by the El Observador association, Human Rights Defenders Project, Earthworks, JASS, Guatemala Human Rights Commission, Institute for Political Studies, NISGUA, International Protection, and the Generalitat Valenciana.”

More resources:

Olivet, Cecilia and Luciana Ghiotto, “Parallel Justice: How the Investment Protection System Endangers the Independence of the Judiciary in Latin America?”, Transnational Institute, 2021. https://www.tni.org/es/publicaci%C3%B3n/justicia-paralela

Free, Prior and Informed Consent Mechanism of Experts on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Council of Human Rights, Contributions from the State of Guatemala. Guatemala, Central America. February 2018.

Sandoval, Ana, “Special Report No. 35 – International Arbitration as a Pressure and Blackmail Mechanism by KCA in the Case of the El Tambor Mining Project”, El Observador, 2022. https://elobservadorgt.org/2022/11/24/informe-especial-35-el-arbitraje-internacional-como-mecanismo-de-presion-y-chantaje-de-kca-en-el-caso-del-proyecto-minero-el-tambor-1/

(Summary of the event held on December 6, prepared by JASS Mesoamerica)