The wind corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, stretching across the southern Mexican states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco and Veracruz, is one of the most important in Latin America in terms of corporate investment and profits. Of the 28 farms in the region, all of which are located principally on indigenous communal lands, construction is halfway complete. This has led to an assault on the way of life and sacred places of the indigenous communities who live in the region, who have been fighting for almost two years to stop the megaproject.

The wind corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, stretching across the southern Mexican states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco and Veracruz, is one of the most important in Latin America in terms of corporate investment and profits. Of the 28 farms in the region, all of which are located principally on indigenous communal lands, construction is halfway complete. This has led to an assault on the way of life and sacred places of the indigenous communities who live in the region, who have been fighting for almost two years to stop the megaproject.

“Of the 15 wind farms that have already been constructed, 10 are on communal land and this is illegal. We are worried because they are attacking our way of life, our health, and the sea,” says Carlos Sanchez, ex-coordinator of the community radio project Totopo, located in the municipality of Juchitán de Zaragoza in Oaxaca. Sanchez also affirmed that the so-called clean technology has begun polluting aquifers with lubricants and other substances that wind turbines require. Additionally, the concrete platforms that form the base of the turbines interrupt traditional agriculture and the vibrations generated cause fish to leave the area and have pushed migratory birds to take alternative routes.

In these communities the local economy is based on fishing and agriculture. The great majority of them do not have paved streets or hospitals, and few of their residents speak Spanish. This region of Mexico has deep-rooted traditions and has maintained its native Zapotec language. More than once the government and multinational corporations have offered to pave the streets and build more schools in return for permits to build wind farms. Some people have been convinced, often through deception or bribery, to sign lease contracts, but those who have maintained their resistance consider this to be a war against indigenous peoples.

Transnational corporations such as Iberdrola, Acciona, Fenosa Natural Gas o Gestamp, Gamesa, Endesa, Eoliatec, Preneal, General Electric, Enron, Energy of France, and Coca-Cola, have launched the offensive in the name of renewable energy, a sector that promises huge profits.

“We will see an explosion in the clean technology sector, which will generate huge business opportunities for the corporations and governments that understand this reality. Because the nation that leads the world in clean energy will lead the global economy in the 21st century,” stated Juan Verde Suárez, advisor to President Barack Obama on international trade, the Hispanic vote, and sustainability, in 2012. In that same year China secured its place as the undisputed leader of the clean energy industry, surpassing the United States with an investment of 67.7 billion dollars–50% above 2011.

The ecological crisis provoked by climate change has been the main argument used globally to push for political and economic promotion of a green economy. The same discourse has been used in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. This region is considered to have great potential for the megaprojects that make up the Mesoamerica Project, a geo-strategic project that extends from Mexico to Colombia and revolves around free trade agreements established primarily with the United States. This economic framework looks to develop a Regional Electricity Market, infrastructure, and highway, maritime, and port transportation services, to increase the flow of merchandise.

The Isthmus region has a production capacity of between 5,000 and 10,000 megawatts in wind energy alone–enough to provide electricity for 18 million inhabitants. This energy, however, is slated primarily for use in the production chains of huge corporations like Wal Mart, FEMSA-Coca-Cola, Heineken, CEMEX and Bimbo, rather than consumption in the communities where it is produced. Meanwhile the price of electricity and fossil fuels is on the rise for everyday Mexicans.

Reducing carbon dioxide emissions has been the main reason given for promoting this type of wind energy production. Since wind energy is determined by Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol to be a “Clean Development Mechanism,” it receives financial support from industrialized countries. Under this system, corporations that invest in renewable energies receive financing from their governments and local governments, generate profits through the production of energy, and at the same time are able to sell “pollution permits”—carbon credits—to other countries or businesses that are unwilling or unable to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Resistance to the wind farm project began with information

“The Mexican Federal government has granted a lot of liberty to corporations to do what they want with our communal lands. We, the original people of this region, matter nothing to the government, we are persecuted and murdered…”, stated a recent emission of Radio Totopo.

Since 2006 Sanchez, together with other members of his community in Juchitan’s 7th Section neighborhood, have been concerned about the effects of the wind farms. With rudimentary equipment they decided to start a community radio project, Totopo Community Radio. The radio was the first alternative media for communications in the Zapotec language. Since its inception, it has aimed to inform the indigenous towns of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec about the implications of the Mesoamerica Project in the wind corridor, Sanchez noted.

Before the creation of the radio station, these indigenous communities had not received information in their native language about the project. From the beginning the radio has represented a threat to groups that benefit from the wind farms, such as the leaders of the Coalition of Worker, Peasants, and Students of the Isthmus (COCEI by its Spanish initials), an arm of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), and government employees of other political parties. But above all, the radio has represented a threat to corporations looking to invest in the region, such as Fenosa Natural Gas.

Before the creation of the radio station, these indigenous communities had not received information in their native language about the project. From the beginning the radio has represented a threat to groups that benefit from the wind farms, such as the leaders of the Coalition of Worker, Peasants, and Students of the Isthmus (COCEI by its Spanish initials), an arm of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), and government employees of other political parties. But above all, the radio has represented a threat to corporations looking to invest in the region, such as Fenosa Natural Gas.

“On March 26, 2013 the government attacked our communications area. The persecution by the state police and the hit men hired by the corporation Fenosa Natural Gas has tried to weaken us,” maintains Sanchez, a founding member of the radio who served as its coordinator for seven years. Throughout his time with the radio he received constant death threats. He reports that once he was stopped and beaten by a paramilitary group, allegedly hired by and made up of members of the Coalition.

Despite being subjected to attacks and persecution, members of the community radio currently have a daily transmission using a ten-watt transmitter and are looking to acquire a thousand-watt transmitter. They consider the radio to be their best tool in the struggle against the wind farm projects.

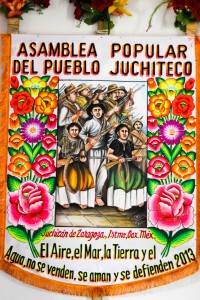

in 2013 the Popular Assembly of the People of Juchitan was formed, which now runs the radio. For several months the assembly maintained a barricade to defend more that 2,000 hectares of communal land, resisting the aggression of hired hit men, the police, and the army with only sticks and machetes.

Fenosa Natural Gas has begun the construction of its first wind farm in Latin America on these indigenous communal lands. It is planned to produce 234 megawatts– the third largest in the region. The company claims it will invest five billion pesos and its energy production will replace the emission of 420,000 tons of carbon dioxide every year. Based on this, Fenosa has begun the process of registering the project as a clean development mechanism with the United Nations.

Currently the communities protesting the project that make up the Assembly of the Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus (APIIDTT) are: San Dionisio del Mar, San Mateo del Mar, San Francisco del Mar, San Blas Atempa, Santa Rosa de Lima, Juchitán, Santa María Xadani, Unión Hidalgo, Álvaro Obregón, and the communal lands of Charis and Zapata. They are on constant alert due to the advance of the projects. Their strength lies in the use of the assembly and consensus descision-making in the villages. In the case of Alvaro Obregon, a part of San Dionisio del Mar, inhabitants decided to declare themselves an autonomous municipality and renounce their relationship with the state and federal government and the political parties.

Autonomous Municipality

Alvaro Obregon is an indigenous Ikojts (Huave) community of approximately 3,171 inhabitants in San Dionisio del Mar. The community has opposed another wind farm project that the corporation Mareña Renewables hoped to construct in an area called La Barra Santa Teresa, also part of the municipality of San Dionisio del Mar. This megaproject would consist of more than 132 wind turbines with an energy capacity of 396 megawatts.

The Ikojts fought back for almost two years, with constant road closures, demonstrations, and confrontations with the police and paramilitary groups, until the wind farm project was suspended (record 739/2012). Even so, attacks and intimidation toward the community have not stopped.

The Ikojts fought back for almost two years, with constant road closures, demonstrations, and confrontations with the police and paramilitary groups, until the wind farm project was suspended (record 739/2012). Even so, attacks and intimidation toward the community have not stopped.

“Saúl Vicente Vázquez, organized direct aggressive actions toward the autonomous municipality on March 2 with a group of hit men and with the support of the government. They are trying to put the brakes on our autonomy,” reported Alejandro López, a member of the community assembly. He also said that although they have achieved the legal suspension of the project, Mareña Renewables will likely move the project to a different community.

On Jan. 1, the council of elders and the general community invoked Convention 169 of the United Nation’s International Labor Organization and declared themselves an autonomous municipality. Mexico Convention 169 ratified the Convention in 1990, thereby promising to protect the right of indigenous peoples to self-determination. However, Vicente Vázquez, the current mayor of Juchitán who at one point served as a member of the United Nations on indigenous matters, refused to recognize the legitimacy of the decision. The assembly complains that later he staged a community assembly by paying people to attend, and named a new authority.

‘We as indigenous people have seen high levels of corruption in the three levels of government. The law is a dead letter to the government. That is why we decided to use Convention 169 and the San Andrés Accords proposed by the Zapatistas,” maintained Pedro López Orozco, member of the assembly of Alvaro Obregon and of the town’s community radio. He added that they will continue to defend their autonomy.

The community’s declaration as an autonomous municipality has revived a spirit of the struggle in these towns, and with the San Andrés Accords as a guide, the Assembly of the Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus decided to hold a session of the first National Indigenous Congress March 29 in Alvaro Obregon. They look to strengthen a corridor of resistance instead of a wind corridor, affirming that there will be going back in their defense of their land and the construction of their project of autonomy.

A few days after the Americas Program visited Alvaro Obregon to report on the process of autonomy and the fight against the wind energy developers, community members announced that twelve members of the Community Police were arrested by local Juchitan police under orders from Saúl Vicente Vázquez. The government charged that it is illegal to name Community Police. The bulletin sent out by the organization held the local and state governments responsible for an confrontation that might occur in the community that could put the safety of Assembly members in danger, for trying to forcibly install illegitimate officials in Alvaro Obregon.