NOTE: This article is the eleventh in a series by the CIP TransBorder Project that examines the water crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Grupo México is likely the single largest water consumer in Sonora. The mining giant almost certainly contaminates more surface water and groundwater than any other private entity.

But no one – except Grupo México executives — knows how much water the company uses and how much it contaminates.

That’s because Grupo México and the entire mining sector in Sonora operate behind a shield of government secrecy, favors, and corruption.

The public guardians of water in Sonora — the State Water Commission (CEA) and the National Water Commission (Conagua) – don’t regulate the company’s water use and don’t monitor its discharges of contaminated water. The federal government’s environmental agencies – SEMARNAT and PROFEPA– are charged with protecting Mexico’s natural resources and assessing the environmental impact of commercial and industrial operations, but instead collaborate with polluters to keep money flowing.[i]

But it is not only this shield of governmental collusion with Grupo México and the mining industry that keeps fundamental facts about the use and destruction of natural resources a secret. Citizens and researchers can’t find out the essential facts of the industry’s operations because the Grupo México mining and metallurgical complexes in northern Sonora are heavily guarded enclaves. Only in extraordinary circumstances – such as the company’s massive contamination of the Sonora River in August 2014 or the company’s heartless disregard for the fate of the 65 mineworkers trapped and dying in its Pasta de Conchos Mine in Coahuila in February 2006 – do some of the dirty secrets of the Grupo México – government collusion come to light.

Sonora like its neighboring states on either side of the international border is caught in a deepening water crisis — one that is largely its own making but now made ever more grim by the onslaught of climate change with its more extreme weather, prolonged droughts, and rising temperatures.

Grupo México is a major player in this crisis because of massive consumption of water. The virtual absence until recently of public, media, and governmental scrutiny of Grupo México’s water-use and environmental practices is a testament to the company’s privileged status in Mexico and especially in Sonora.

This lack of scrutiny is all the more stunning given that its two mining complexes are situated in the upper basins of Sonora’s two most important rivers: the Buenavista del Cobre mine in Cananea in the Río Sonora basin which feeds the state’s capital and most populous city, and the La Caridad mining and metallurgical complex at the company town of Nacozari de García and next to the La Angostura dam and reservoir on Río Bavispe which feeds the mighty Yaqui River and sustains the state’s most productive agricultural region in the Yaqui Valley.

Recently, the expansion of Grupo México’s excavation and processing activities in the Cananea region are also increasingly putting the San Pedro river basin at risk, underscoring the cross-border implications and political repercussions of the expansion of this transnational mining company.

Since 2010 a water war has set Sonora on edge. The Yaqui Water War concerns the historic use and the water rights of the Sonora and Yaqui Rivers. Yet despite its depredation of the water resources of both rivers, the central role of Grupo México in depleting and contaminating these two river basins has been largely unexamined – due to its privileged status with the state and federal governments and the impenetrability of its guarded mining enclaves.

Government and company secrets obstruct a complete accounting of the extent of Grupo México’s depredations of the Sonora, Yaqui, and San Pedro Rivers. Despite the social, economic, and political tensions of the Yaqui Water War and despite the company’s responsibility for the worst environmental disaster in the history of mining in Sonora, there are still only bits and pieces of information available about the role of Grupo México in accelerating the water crisis that is threatening the future of Sonora and the border region.

Probably only Grupo México knows how much surface and groundwater it extracts from the aquifers associated with the Yaqui, San Pedro, and Sonora Rivers. Even the government, which issues the company hundreds of permits for water consumption and land use, has only the scantiest data about the company’s actual water use and environmental impacts.

The involved government agencies pose as regulators, monitors, protectors of the nation’s natural resources, when in fact, as events have so starkly demonstrated, the agencies that are charged with controlling Grupo México serve more as facilitators and enablers. SEMARNAT, PROFEPA, CEA, and Conagua are in effect (and by choice) bystanders in the plundering of Sonora’s water resources.

Mine Drinks Public’s Water in Cananea

Governmental corruption and deception obstruct a full account of Grupo México’s water consumption and water contamination in Sonora. Despite the August 2014 flood of toxics in the Río Sonora, Grupo México has maintained a lockdown on information about its use of Sonora’s water resources. At the same time, however, Grupo México floods business information markets with a steady stream of media releases boasting about its low-cost production, surge in revenues, and oligopolistic hold on mining, transportation, and ancillary service industries.

Since 1997 Conagua has issued a stream of permits to Grupo México to extract groundwater in aquifers that the agency itself has repeatedly declared to be severely over-exploited – where natural recharge rates are far exceeded by extraction rates. If one were to accept that the firm used only the amount specified in its Conagua permits, the copper mining operations in Cananea, according to one media report, use 75% more than the seven municipalities in the Sonora River basin.[ii]

In 2002-2005 Conagua granted nine concessions for mining in the Cananea area to Grupo México for water extraction from two aquifers that are covered by a federal ban on the drilling of new water wells, according to media reports in Mexico.[iii] The restrictions, issued in 1967 and 184, prohibited all new water wells unless they were explicitly for urban public use.

The permits issued by the Vicente Fox administration allowed the extraction of 28 million of cubic meters of water from aquifers that Conagua describes as severely over-exploited.

Until recently Grupo México’s held water permits, including five issued by Conagua in 2012, for pumping in Sonora river aquifers (notably by the Bacanuchi tributary that was flooded with sulfuric acid in August 2014). According to media reports, Conagua in 2013 granted Grupo México a wide-ranging permit to begin drilling in the San Pedro River basin as part of its multi-billion dollar expansion in the Cananea region.

According to a report by Proceso and other media reports, this latest permit, like the previous ones, specifies that the water should be used only for urban public consumption (“uso público urbano”)– not for mining or industrial operations.[iv] None of these water-extraction permits includes permission for the discharge of used water, whether contaminated or not, back into the aquifer.

Conagua has not been forthcoming about the permits it has issued to Grupo México for either its Cananea or Nacozari operations. Nor has the federal agency provided any calculations of the quantity of water consumed – with or without permits — at Sonora’s largest mines. Upon questioning by congressional deputies, Conagua director David Korenfeld did, however, acknowledge that at least for four years (1999-2002) the Buenvavista mine used potable water for mining activities under an urban-use permit.[v]

Corruption in Mexico’s Water Agency

Conagua is one of Mexico’s most corrupt, nontransparent, and unaccountable federal agencies. Water permits are bought and sold regardless of water-use restrictions or well-drilling prohibitions. Permits for one well commonly are used to drill a battery of wells. The permits on record in Conagua regional offices don’t even closely reflect the water-use patterns in any region because of the proliferation of illegal, cloned, or “irregular” permits that exist.

Conagua’s water-extraction permits for Grupo México’s Cananea operations are what are commonly known as “concesiones irregulars” – permits that don’t conform to the national water law. Yet especially in the arid states, there are more irregular water permits than legal ones, given restrictions on new wells in overexploited water basins.

The Mexican government hasn’t filed criminal or civil charges against Grupo México for what a federal government official called the “worst natural disaster” in Mexico’s mining history.” That should be of no surprise. The economic clout of Mexico’s largest mining company accounts for Grupo México’s continued privileged status and impunity. Since the 1980s the federal government (under both PRI and PAN leadership) has effectively colluded with Grupo México to evade Mexico’s environmental and water laws.

Conagua isn’t the only federal agency that has in effect allowed Grupo México to mine and process copper outside of the government’s environmental and water-use regulations. The Buenavista mine has received more than five-dozen federal permits from SEMARNAT, PROFEPA, Conagua, and the economic ministry. PROFEPA, the federal agency in charge of enforcing environmental regulations, has categorized Grupo México as a “clean industry,” thereby facilitating new permits for changes in land-use, such as clearing forested land for mining operations and tailings ponds. Most of the federal permits don’t expire until after 2050.

Considering only Conagua’s collaboration with Grupo México’s Cananea operations, there exist at least three examples of this collusion:

1) The water permits issued in the past two decades have been for domestic use, not for industrial use, thereby avoiding, at least on paper, prohibitions of major water pumping in the aquifers of Sonora River’s upper basin and in the San Pedro aquifer;

2) When issuing the domestic-use permits, Conagua didn’t issue permits needed for the storing or dumping of contaminated water; and

3) Conagua didn’t revoke the permits after reported incidents of groundwater and surface water contamination of the Sonora River basin in the several years prior to the disastrous August 2014 spill into the Bacanuchi, the northernmost tributary of the Sonora River.

In Mexico and in the United States, the impact of Mexico’s mining boom over the past two decades has received little attention, in part because drug-related violence by organized crime and law enforcement have dominated the news, but also because the mining industry and the government have refused to divulge vital information about mining operations.

La Caridad as Government Charity

Conagua, the State Water Commission (CEA), and Grupo México have not been forthcoming about the consumption and contamination of water in the Yaqui River basin. The federal government’s environmental agencies have ignored Grupo México’s systemic disregard for the environmental consequences of their operations. And neither the federal government nor the state of Sonora have protected the ejidos and towns near its mines from displacement and environmental contamination, despite a long history of complaints.

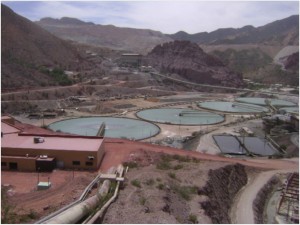

Grupo México’s La Caridad mine and metallurgical complex near Nacozari de Garcia is a tightly guarded enclave. Situated next to La Angostura, Sonora’s first major dam and reservoir, La Caridad has been the major beneficiary of the dam.

Grupo México says it pays fees to Conagua for its water consumption at all its operations “with the exception of what it pumps water directly from the reservoir” – apparently without any fees. As it states in its annual report, “Mexicana de Cobre (La Caridad) pumps water directly from the La Angostura, which is near the mine and the processing plants.”[i]

Mexicana de Cobre operates one of the three acueducts that pumps water from the Yaqui River basin.

The pumping station at La Angostura transfers a reported 26 Mm3 of water to the company’s copper and molybdenum mining operations and processing plants. Under a 1991 agreement between the Yaquis and Conagua and CEA (opposed by committees in Vícam and Pótam but signed by eight governors), the Yaqui-Guamas aqueduct transfers 22Mm3 of water from the Yaqui Valley to Guaymas, Empalme, and San Carlos.

The Independencia aqueduct has the capacity to transfer 75Mm3 from the middle Yaqui River basin at the Novillo reservoir to Hermosillo.

The exact amount of water that Grupo México’s Mexicana de Cobre complex extracts from the river and by its wells within the vast complex – encompassing 104,990 hectares – is not publicly known. However, the three aqueducts alone extract 123 Mm3 of water from the Yaqui River basin, which is about 20% more than the total capacity of La Angostura. When ordering the construction of La Angostura, President Lázaro Cárdenas decreed that the Yaquis had water rights to half the reservoir’s capacity. But these promised water rights have never been implemented, which helps explains the vehement Yaqui opposition to the Novillo-Hermosillo aqueduct.

Nacozari de García is a quintessential mining town. It is also the closest large town to La Angostura, which lies about 20 miles to the city’s southeast. Despite its proximity to the reservoir and its role as Grupo México’s offices for La Caridad, the city has for decades suffered severe water shortages. While the mine has free access to the reservoir, neither the mine nor the government has created the infrastructure necessary to supply Nacozari with water from Angostura.

The federal government’s privileged treatment of Grupo México continues from administration to administration, whether PAN or PRI presides. A recent example of how the federal government gives Grupo México free rein to exploit the country’s natural resources is the company’s plan to tap into the dam’s hydroelectric capacities – without regard to environmental impacts, Yaqui water rights, or impact on other traditional users of Yaqui River water.

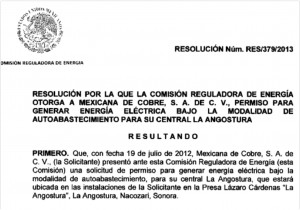

In September 2012 the Federal Energy Regulation Commission granted Grupo México permission to establish a 7.00 MW hydroelectric facility to generate an estimated 41.00 GWh of electricity to serve the needs of La Caridad. According to the permit, Grupo México would begin generating electricity in September 2014.[ii]

There was no fee specified on the grounds that the electricity would not be for sale but for self-sufficiency (“autobastecimiento”). Furthermore, the federal commission noted that the “opportune and efficient provision of energy is one of the pillars that supports national development and constitutes a necessary condition to attain its goals of growth.” What is more, the use of La Angostura water would “respond chiefly to the company’s goals to increase the competitiveness of the production processes of its various businesses.”

Before seeking approval of the federal energy commission, Conagua on September 29, 2010 had granted Grupo México a water-use permit (“título de concesión”) to “exploit, use, or take advantage of national surface waters amounting to 416,669,000 cubic meters of water annually.” Conagua reports that La Angostura has a capacity 864 Mm3 although other Conagua reports note that effective capacity because of silt accumulation has decreased to 700 Mm3.

The Conagua permit was issued without any environmental impact study. The permit for Grupo México to use such immense quantities of water in the upper Yaqui River basin came at the time that the anti-Novillo-Hermosillo coalition was organizing large demonstrations. The Yaquis were developing legal cases against the aqueduct that, among other things, asserted that SEMNARNAT’s environmental impact statement on the aqueduct was grossly inadequate since it didn’t take into account the impact on the river because of reduced flows.

Understandably, the focus of the anti-aqueduct coalition was on the Conagua-approved and -financed transfer of water from the Yaqui River basin to Hermosillo in the depleted Sonora River basin. Conagua tried to assuage the coalition’s concerns that the aqueduct would leave the lower Yaqui River basin without a dependable supply of water, especially during droughts with the still-unconfirmed story that it had bought existing water rights from small farmers in the middle river basin. What the federal water agency didn’t say – and still hasn’t acknowledged – is that the highly questionable water permits issued to Grupo México and other mining operations were responsible for vast withdrawals of water from both the Sonora and Yaqui basins.

Prior to the federal energy commission’s approval of Grupo México’s permission, the company had also succeeded in securing a favorable ruling by SEMARNAT, the federal environmental ministry. SEMARNAT waived the environmental impact statement for the hydroelectric plant to be operated by México Generadora de Energía (MGE).

The determination followed SEMARNAT’s practice of narrowing the scope of the possible environmental impact to the construction of the hydroelectric plant rather than considering the manifold impacts on water quality, wildlife, and the riparian environment. SEMARNAT ruled on January 27, 2011that “there would be no need for any presentation of a study of environmental impact for its authorization.” As the Union of Concerned Scientists has concluded, hydroelectric plants need to be carefully regulated. If, for example, the water used for electricity generation includes water from the lower levels of a reservoir the oxygen level of the released water will be insufficient to maintain river life.[iii]

Grupo México created MGE in 2005 and received approval by the Energy Regulatory Commission to generate electricity for the company’s mining and metallurgical operations in Sonora. Grupo México told its stockholders that MGE would produce electrical energy to its Mexican open pit mining operations “at a discount of the cost charged by CFE (Federal Electricity Commission).” Grupo México boasted that its MGE subsidiary formed part of the company’s commitment of strengthening its mining division position as one of the world’s low cost producers.”[iv]

Although not mentioned by Grupo México, free, easy and under-the-table access to water in Mexico is likely one of the reasons that the transnational firm is one of the world’s low cost producers.

Like the “irregular” water permits Conagua granted Grupo México, the federal energy regulatory commission’s authorization was also irregular. The commission issued its authorization in September 2013 for the construction of the company’s hydroelectric plant in September 2013, but Grupo México had been building the facility since July 2012. In other words, the commission ruled on Grupo México’s request at mid-point in the construction process, creating the assumption that Grupo México had been assured of the commission’s approval. While this process was on the face of it irregular, it is normal in corporate-governmental relations in Mexico.

Until the late 1980s, Grupo México’s Buenavista and La Caridad mining complexes were government-owned mining corporations. Yet while the federal government held the title to these massive operations, they were heavily financed through NAFINSA, the government’s development bank, with most of the debt held by foreign investors and banks. When the government privatized La Caridad, the enterprise was heavily indebted – owing $1.36 billion to foreign banks.[v]

This history as a heavily indebted government enterprise established a pattern of free access to water and the lack of enforcement of environmental, land-use, and occupational safety regulations.

Essentially, La Angostura functions as Grupo México’s private dam and reservoir. Except for one access road to the reservoir for tourists and fishermen, Grupo México strictly controls all the entry points to the mine and the dam from the west and south.

What is becoming clear is that the government and the mining industry need provide accurate public information on water consumption and water contamination by mining. While primarily a Mexican concern, the boom in mining exploration and extraction in Mexico’s northern borderlands – in Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, and Coahuila, especially – has international repercussions.

The impact of Grupo Mexico’s operations and of other companies including Peñoles,and Grupo Frisco, don’t stop at the international border. They are putting at risk the quantity and quality of transboundary surface water flows and groundwater basins that span the border.

FOOTNOTES:

[i] Grupo México, Southern Peru Copper, “Formulario 10-K 2013,” Submitted in Washington, DC., at http://www.southernperu.com/esp/relinv/2013/10K/10k131231e.pdf According to Grupo México: Los derechos por uso de agua se establecen en la Ley Federal de Derechos, la cual distingue varias zonas de disponibilidad con diferentes tarifas por unidad de volumen, dependiendo de cada zona, con la excepción de Mexicana de Cobre. Todas nuestras operaciones tienen una o varias concesiones de agua y bombean de pozos el agua que necesitan.”

[ii] “Resolución por la que la Comisión Reguladora de Energía ortorga a Mexicana de Cobre, S.S. de C. V., permiso para generar energía eléctrica bajo la modalidad de autobastecimiento para su central La Angostura,” Comisión Reguladora de Energía, Núm. RES/379/2013, 19 de septiembre de 2013.

[iii] Union of Concerned Scientists, “Environmental Impact of Hydroelectric Plants,” at http://www.ucsusa.org/clean_energy/our-energy-choices/renewable-energy/environmental-impacts-hydroelectric-power.html#.VHIywVfF8Xc

[iv] Grupo México, press release, n.d., at: http://gmexico.com.mx/files/PRMGGEINICIAVENTAING.pdf Before it began work on the hydroelectric plant, MGE, which is based on Grupo México’s property alongside La Angostura, was operating two gas-fired electricity generating plants at the La Caridad and Buenavista mining complexes. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission had approved the creation of MGE in 2005 for the purpose of operating gas-fired plants, and it wasn’t until later in the decade that Grupo México came before the commission with the request for a MGE-run hydroelectric plant.“ S&P Rates MGE,” Reuters, Nov. 16, 2012, 2012.

[v] “Mine Sold in Mexico,” Nov. 4, 1988, New York Times, at http://www.nytimes.com/1988/11/04/business/mine-sold-in-mexico.html

[i] SEMARNAT is the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, while PROFEPA (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente) is a decentralized branch of SEMARNAT that inspects, monitors environmental agreements, and is charged with enforcing the country’s environmental regulations.

[ii] Proceso online, Sept. 23, 2014; Georgina Howard, “Permite Conagua desorden minero,” Reporte Indigo, Sept. 30, 2014. Media reports cite a PRD congressional commission investigating the August 6, 2014 contamination.

[iii] Angélica Enciso L, “Minera Buenavista del Cobre opera en Cananea con permisos de agua irregulars,” La Jornada, Sept. 23, 2014.

[iv] Proceso online, Sept. 23, 2014 Georgina Howard, “Permite Conagua desorden minero,” Reporte Indigo, Sept. 30, 2014. Media reports cite a PRD congressional commission investigating the August 6, 2014 contamination.

[v] “Explotó Grupo México agua de ríos ilegalmente: Conagua,” La Jornada, Sept. 30, 2014.[ii] Proceso online, Sept. 23, 2014; Georgina Howard, “Permite Conagua desorden minero,” Reporte Indigo, Sept. 30, 2014. Media reports cite a PRD congressional commission investigating the August 6, 2014 contamination.

[iii] Angélica Enciso L, “Minera Buenavista del Cobre opera en Cananea con permisos de agua irregulars,” La Jornada, Sept. 23, 2014.

[iv] Proceso online, Sept. 23, 2014 Georgina Howard, “Permite Conagua desorden minero,” Reporte Indigo, Sept. 30, 2014. Media reports cite a PRD congressional commission investigating the August 6, 2014 contamination.

[v] “Explotó Grupo México agua de ríos ilegalmente: Conagua,” La Jornada, Sept. 30, 2014.

All articles in this 13-part series:

1. The Yaqui Water War

https://www.americas.org/archives/13463

2. Sonora and Arizona’s Uncertain Water Futures

https://www.americas.org/archives/13485

3. The Illusions of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/13852

4. Sonora Launches Controversial Megaprojects in Response to Water Crisis

https://www.americas.org/archives/13854

5. Origins and Disappearance of the Yaqui River

https://www.americas.org/archives/13892

6. The Old and New Sonoras: The Context for Sonora’s Water Wars

https://www.americas.org/archives/14008

7. Making the Desert Bloom: The Rise of Sonora’s Hydraulic Society

https://www.americas.org/archives/14017

8. The Damming of the New Sonora

https://www.americas.org/archives/14025

9. Mining Boom in the Sierra Madre

https://www.americas.org/archives/14040

10. Mexico’s Three Mining Giants

https://www.americas.org/archives/14044

11. Mining Water in Sonora: Grupo México’s “Irregular” Water Permits in the Sonora, Yaqui, and San Pedro River Basins

https://www.americas.org/archives/13998

12. Making Mining Dreams Come True in Mexico

https://www.americas.org/archives/14055

13. Mining, Megaprojects, and Metrosexuals in Sonora