Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of a three-part series on migrant rights by journalist and immigration activist David Bacon. This article is taken from the report “Displaced, Unequal and Criminalized – Fighting for the Rights of Migrants in the United States” that examines the origins of the current migratory labor phenomenon, the mechanisms that maintain it, and proposals for a more equitable system. The Americas Program is proud to publish this series in collaboration with the author.

A political alliance is developing between countries with a labor export policy and the corporations who use that labor in the global north. Many countries sending migrants to the developed world depend on remittances to finance social services and keep the lid on social discontent over poverty and joblessness, while continuing to make huge debt payments. Corporations using that displaced labor share a growing interest with those countries’ governments in regulating the system that supplies it.

Increasingly, the mechanisms for regulating that flow of people are contract labor programs—called “guest worker” or “temporary worker” programs in the U.S., or “managed migration” in the UK and much of the EU. With or without these programs, migration to the U.S. and other industrial countries is a fact of life. Despite often using rhetoric that demonizes immigrants, the U.S. Congress is not debating the means for ending migration. Nothing can, short of a radical reordering of the world’s economy.

Nor are the current waves of immigration raids and deportations in the U.S. intended to halt it. In an economy in which immigrant labor plays a critical part, the price of stopping migration would be economic crisis. The intent of immigration policy is managing the flow of people, determining their status here in the U.S., in the interest of those who put that labor to work.

Migrants are human beings first however, and their desire for community is as strong as the need to labor. The use of neoliberal reforms and economic treaties to displace communities, to produce a global army of available and vulnerable workers, has a brutal impact. Existing and proposed free trade agreements between the U.S. and Mexico, Canada, Central America, Peru, Colombia, Panama, South Korea, and Jordan not only do not stop the economic transformations that uproot families and throw them into the migrant stream—they push that whole process forward.

On a world scale, the migratory flow caused by displacement is still generally self-initiated. In other words, while people may be driven by forces beyond their control, they move at their own will and discretion, trying to find survival and economic opportunity, and to reunite their families and create new communities in the countries they now call home. But the idea of managing the flow of migration is growing.

It is the contention of this paper that these global economic forces are driving the development of U.S. immigration policy. Increasingly, the political fault lines that divide the U.S. immigrant rights movement are determined by decisions to either support this general trend in policy, and its political representatives in Washington DC, or to oppose it and create a social movement for equality and rights based in the communities of migrants themselves.

The development of a labor supply and labor management system to govern the flow of migrants, that is, of people, requires increasingly ferocious enforcement. With the criminalization of work for undocumented migrants a quarter century ago, along with the resurrection of a contract labor program for migrants, in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, the parameters were set for the debates over immigration policy that continue to the present. Today immigration raids and enforcement actions, harsh and racist legislation, and the hysteria that comes with all this, are sweeping our country. Today’s migrants have become needed low-wage labor and criminals at the same time.

This paper will outline first the global economic forces driving displacement and migration, and their impact on communities. It will then outline the basic structure and purpose of U.S. immigration policy, and the basic proposals for changing it. It will examine the division between mainstream, Washington DC-based supporters of corporate immigration reform and community- and labor-based groups who call for an alternative, and finally it will outline their proposals for an alternative based on human and labor rights.

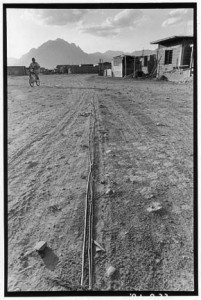

We begin with the examination of one particular stream of migrants, of indigenous people from Oaxaca, both because their experience is similar to others, but also because organizations in the communities involved have articulated a sophisticated analysis of the system in which they move.

Where the Flow of People Begins

Rufino Domínguez, the former coordinator of the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations, who now heads the Oaxacan Institute for Attention to Migrants, estimates there are about 500,000 indigenous people from Oaxaca living in the U.S., 300,000 in California alone.

According to Rick Mines, author of the 2010 Indigenous Farm Worker Study, “the total population of California’s indigenous Mexican farm workers is about 120,000 … a total of 165,000 indigenous farm workers and family members in California.” Counting the many indigenous people living and working in urban areas, the total is considerably higher, he says, easily meeting Domínguez’ estimate.

The study counted 54,000 people who had emigrated from 350 Oaxacan towns, or about 150 per town. Given the size of many small communities, this supports the widespread assertion of many indigenous Oaxacans that some towns have become depopulated, or are communities of the very old and very young, where most working-age people have left to work in the north.

“In the early 1990s there were about 35,000 indigenous farm workers in California,” Mines says, “while in the 2004 to 2008 period there were about four times as many, or 120,000 indigenous Mexican farm workers.” In addition, indigenous people made up 7% of Mexican migrants in 1991-3, the years just before the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement. In 2006-8 they made up 29% — four times more.

California has a farm labor force of about 700,000 workers, so the day is not far off when indigenous Oaxacan migrants may make up a majority. They are truly the workforce that has been produced by NAFTA and the neoliberal changes in the global economy. Further, “the U.S. food system has long been dependent on the influx of an ever-changing, newly-arrived group of workers that sets the wages and working conditions at the entry level in the farm labor market,” Mines says. The rock-bottom wages paid to this most recent wave of migrants – Oaxaca’s indigenous people – sets the wage floor for all the other workers in California farm labor, keeping the labor cost of California growers low, and their profits high.

Economic crises provoked by the North American Free Trade Agreement and other economic reforms are now uprooting and displacing these Mexicans in the country’s most remote areas, where people still speak languages that were old when Columbus arrived from Spain. While farm workers 20 and 30 years ago came from parts of central Mexico with a larger Spanish presence, migrants today come increasingly from indigenous communities. “There are no jobs, and NAFTA forced the price of corn so low that it’s not economically possible to plant a crop anymore,” Dominguez says. “We come to the U.S. to work because we can’t get a price for our product at home. There’s no alternative.”

As he points out, U.S. trade and immigration policy are linked together. They are part of a single system, not separate and independent policies. The negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement was in fact an important step in the development of this relationship.

Since NAFTA’s passage in 1993, the U.S. Congress has debated and passed several new trade agreements – with Peru, Jordan, Chile, and the Central American Free Trade Agreement. At the same time it has debated immigration policy as though those trade agreements bore no relationship to the waves of displaced people migrating to the U.S., looking for work. Meanwhile, a rising tide of anti-immigrant hysteria has increasingly demonized those migrants, leading to measures to deny them jobs, rights, or any pretense of equality with people living in the communities around them. To resolve any of these dilemmas, from adopting rational and humane immigration policies to reducing the fear and hostility towards migrants, the starting point must be an examination of the way U.S. policies have both produced migration, and criminalized migrants.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act

and NAFTA

Trade negotiations and immigration policy were formally joined together when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986. Immigrant rights activists campaigned against the law because it contained employer sanctions, prohibiting employers for the first time on a federal level from hiring undocumented workers. Those advocates said the proposal amounted to criminalizing work for the undocumented. IRCA’s liberal defenders pointed to its amnesty provision as a gain that justified sanctions, and the bill eventually did enable over 4 million people living in the U.S. without immigration documents to gain permanent residence. Showing the broad bipartisan consensus for the bill’s approach to immigration in Washington DC, the bill was signed into law by Ronald Reagan, a Republican and the country’s most conservative president up to that time.

Few noted one other provision of the law. IRCA set up a Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Economic Development to study the causes of immigration to the U.S. The commission was inactive until 1988, but began holding hearings when the U.S. and Canada signed a bilateral free trade agreement. After Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari made it plain he favored a similar agreement with Mexico, the commission made a report to President George Bush Sr. and to Congress in 1990. It found, unsurprisingly, that the main motivation for coming to the U.S. was economic. To slow or halt this flow, it recommended “promoting greater economic integration between the migrant sending countries and the United States through free trade” and that “U. S. economic policy should promote a system of open trade.” It concluded that “the United States should expedite the development of a U.S.-Mexico free trade area and encourage its incorporation with Canada into a North American free trade area,” while warning that “it takes many years – even generations – for sustained growth to achieve the desired effect.”

Few noted one other provision of the law. IRCA set up a Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Economic Development to study the causes of immigration to the U.S. The commission was inactive until 1988, but began holding hearings when the U.S. and Canada signed a bilateral free trade agreement. After Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari made it plain he favored a similar agreement with Mexico, the commission made a report to President George Bush Sr. and to Congress in 1990. It found, unsurprisingly, that the main motivation for coming to the U.S. was economic. To slow or halt this flow, it recommended “promoting greater economic integration between the migrant sending countries and the United States through free trade” and that “U. S. economic policy should promote a system of open trade.” It concluded that “the United States should expedite the development of a U.S.-Mexico free trade area and encourage its incorporation with Canada into a North American free trade area,” while warning that “it takes many years – even generations – for sustained growth to achieve the desired effect.”

The negotiations that led to NAFTA started within months of the report. As Congress debated the treaty, Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari toured the United States, telling audiences unhappy at high levels of immigration that passing NAFTA would reduce it by providing employment for Mexicans in Mexico. Back home Salinas and other treaty proponents made the same argument. NAFTA, they claimed, would set Mexico on a course to become a first-world nation. “We did become part of the first world,” says Juan Manuel Sandoval, coordinator of the Permanent Seminario on Chicano and Border Studies at Mexico City’s National Institute of Anthropology and History. “The back yard.”

NAFTA, however, did not lead to rising incomes and employment, and therefore, it did not decrease the flow of migrants to the U.S. Instead, it became an important source of pressure on Mexicans, particularly Oaxacans, to migrate. The treaty forced yellow corn grown by Mexican farmers without subsidies to compete in Mexico’s own market with corn from huge U.S. producers, subsidized by the U.S. farm bill. Agricultural exports to Mexico more than doubled during the NAFTA years, from $4.6 to $9.8 billion annually – $2.5 billion in 2006 in corn alone. In January and February of 2008, huge demonstrations in Mexico sought to block the implementation of the agreement’s final chapter, which lowered the tariff barriers on white corn and beans.

As a result of a growing crisis in agricultural production, by the 1980s Mexico had already become a corn importer. Corn imports rose from 2,014,000 to 10,330,000 tons from 1992 to 2008. According to Alejandro Ramírez, general director of the Confederation of Mexican Pork Producers, Mexico imported 30,000 tons of pork in 1995, the year NAFTA took effect. By 2010 pork imports, almost all from the U.S., had grown over 25 times, to 811, 000 tons. As a result, pork prices received by Mexican producers dropped 56%.

Imports had a dramatic effect on Mexican jobs. “We lost 4000 pig farms,” Alejandro Ramírez estimates. “On Mexican farms, each 100 animals produce 5 jobs, so we lost 20,000 farm jobs directly from imports. Counting the 5 indirect jobs dependent on each direct job, we lost over 120,000 jobs in total. This produces migration to the U.S. or to Mexican cities — a big problem for our country.” Once Mexican meat and corn producers were driven from the market by imports, the Mexican economy was left vulnerable to price changes dictated by U.S. agribusiness or U.S. policy. “When the U.S. modified its corn policy to encourage ethanol production,” he charges, “corn prices jumped 100% in one year.”

NAFTA then prohibited price supports, without which hundreds of thousands of small farmers found it impossible to sell corn or other farm products for what it cost to produce them. The CONASUPO system, in which the Mexican government bought corn at subsidized prices, turned it into tortillas and sold them in state-franchised grocery stores at subsidized low prices, was abolished.

Mexico couldn’t protect its own agriculture from the fluctuations of the world market. A global coffee glut in the 1990s plunged prices below the cost of production. A less entrapped government might have bought the crops of Veracruz farmers to keep them afloat, or provided subsidies for other crops. But once free market structures were in place prohibiting government intervention to help them, those farmers paid the price. Veracruz campesinos joined the stream of workers headed north. There they became an important part of the workforce in the Smithfield pork processing plant in North Carolina, as well as in other industries.

U.S. companies were allowed to own land and factories, eventually anywhere in Mexico, without Mexican partners. U.S.-based Union Pacific, in partnership with the Larrea family, became the owner of the country’s main north-south rail line, and immediately discontinued virtually all passenger service, as railroad corporations had done in the US. Mexican rail employment dropped from over 90,000 to 36,000. Facing privatization, railroad workers mounted a wildcat strike to try to save their jobs, but they lost and their union became a shadow of its former presence in Mexican politics.

Slashing wages in privatized enterprises and gutting union agreements only increased the wage differential between the U.S. and Mexico. According to Garrett Brown of the Maquiladora Health and Safety Network, the average Mexican wage was 23% of the U.S. manufacturing wage in 1975. By 2002 it was less than an eighth, according to Mexican economist, and former Senator Rosa Albina Garabito. Brown says that since NAFTA went into effect, real Mexican wages dropped by 22%, while worker productivity increased 45%.

Low wages are the magnet used to attract US and other foreign investors. In mid-June, 2006, Ford Corporation, already one of Mexico’s largest employers, announced it would invest $9 billion more in building new factories. Meanwhile, Ford said it was closing at least 14 US plants, eliminating the jobs of tens of thousands of U.S. workers. Both moves were part of the company’s strategic plan to stem losses by cutting labor costs drastically and moving production. When General Motors was bailed out by the U.S. government in the current recession, it closed a dozen U.S. plants and laid off tens of thousands of workers. Its plans for building new plants in Mexico went forward without any hindrance.

In NAFTA’s first year, 1994, one million Mexicans lost their jobs, by the government’s count, when the peso was devalued. To avert the sell off of short-term bonds and a flood of capital to the north. U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin engineered a $20 billion loan to Mexico, which was paid to bondholders, mostly US banks. In return, U.S. and British banks gained control of the country’s financial system. Mexico had to pledge its oil revenue to pay off foreign debt, making the country’s primary source of income unavailable for social needs.

As the Mexican economy, especially the border maquiladora industry, became increasingly tied to the U.S. market, Mexican workers lost jobs when the market for what those factories produced shrank during U.S. recessions. In 2000-2001 400,000 jobs were lost on the U.S./Mexico border, and in the current recession, thousands more have been eliminated.

Displacement – A Product of Free Market Reforms

All of these policies produced displaced people, who could no longer make a living or survive as they’d done before. The rosy predictions of NAFTA’s boosters that it would raise income and slow migration proved false. The World Bank, in a 2005 study made for the Mexican government, found that the extreme rural poverty rate of 35% in 1992-4, prior to NAFTA, jumped to 55% in 1996-8, after NAFTA took effect. This could be explained, the report said, “mainly by the 1995 economic crisis, the sluggish performance of agriculture, stagnant rural wages, and falling real agricultural prices.”

By 2010 53 million Mexicans were living in poverty, according to the Monterrey Institute of Technology — half the country’s population. About 20% live in extreme poverty, almost all in rural areas. The growth of poverty, in turn, fueled migration. In 1990 4.5 million Mexican-born people lived in the U.S. A decade later, that population more than doubled to 9.75 million, and in 2008 it peaked at 12.67 million. About 11% of all Mexicans now live in the U.S. About 5.7 million were able to get some kind of visa, but another 7 million couldn’t, and came nevertheless.

People were migrating from Mexico to the U.S. long before NAFTA was negotiated. Juan Manuel Sandoval emphasizes that “Mexican labor has always been linked to the different stages of U.S. capitalist development since the 19th century – in times of prosperity, by the incorporation of big numbers of workers in agricultural, manufacturing, service and other sectors, and in periods of economic crisis, by the deportation of Mexican laborers back to Mexico in huge numbers.” The current wave of deportations – one million people in the last two years – bears him out.

From 1982 through the NAFTA era, successive economic reforms produced more migrants. The displacement of people had already grown so large by 1986 that the commission established by IRCA was charged with recommending measures to halt or slow it.

Its report urged that “migrant-sending countries should encourage technological modernization by strengthening and assuring intellectual property protection and by removing existing impediments to investment” and recommended that “the United States should condition bilateral aid to sending countries on their taking the necessary steps toward structural adjustment. Similarly, U.S. support for non-project lending by the international financial institutions should be based on the implementation of satisfactory adjustment programs.” The IRCA commission report even acknowledged the potential for harm by noting “efforts should be made to ease transitional costs in human suffering.”

The North American Free Trade Agreement, however, was not intended to relieve human suffering. In 1994, the year the treaty took effect, U.S. speculators began selling off Mexican government bonds. According to Jeff Faux, founding director of the Economic Policy Institute, “the peso crash of December, 1994, was directly connected to NAFTA, which had created a speculative bubble for Mexican assets that then collapsed when the speculators cashed in.”

“It is the financial crashes and the economic disasters that drive people to work for dollars in the U.S., to replace life savings, or just to earn enough to keep their family at home together,” says Harvard historian John Womack. “The debt-induced crash in the 1980s, before NAFTA, drove people north…The financial crash and the Rubin-induced reform of NAFTA, New York’s financial expropriation of Mexican finances between 1995 and 2000, drove the economically wrecked, dispossessed and impoverished north again.”

The U.S. immigration debate has no vocabulary that describes what happens to migrants before they cross borders – the factors that force them into motion. In the U.S. political debate, Veracruz’s uprooted coffee pickers or unemployed workers from Mexico City are called immigrants, because that debate doesn’t recognize their existence before they leave Mexico. It would be more accurate to call them migrants, and the process migration, since that takes into account both people’s communities of origin and those where they travel to find work.

Displacement itself becomes an unmentionable word in the Washington discourse. Not one immigration proposal in Congress in the quarter century since IRCA was passed tried to come to grips with the policies that uprooted miners, teachers, tree planters and farmers, in spite of the fact that Congress members voted for these policies. In fact, while debating bills to criminalize undocumented migrants and set up huge guest worker programs, four new trade agreements were introduced, each of which would cause more displacement and more migration.

David Bacon is a writer and photojournalist based in Oakland and Berkeley, California. He has been a reporter and documentary photographer for 18 years, shooting for many national publications. He has exhibited his work nationally, and in Mexico, the UK and Germany. Bacon covers issues of labor, immigration and international politics and is an associate editor at Pacific News Service and a regular contributor to the Americas Program.

The report “Displaced, Unequal and Criminalized – Fighting for the Rights of Migrants in the United States” was prepared for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.