Carlos Montemayor broke a political taboo. An astute social analyst and prolific writer, Montemayor’s novels about the leftist guerrilla uprisings and state repression of the 1960s and 1970s recovered the memory of the dirty war from the historical dustbin. Although the Mexican government still guards the fates of hundreds of people disappeared by its security forces during the dirty war as state secrets, Montemayor’s literary contributions helped puncture an official silence at a time when popular forces were struggling to make Mexico a more democratic and just country.

Montemayor’s untimely death on February 28 came during a year when Mexico celebrates the twin anniversaries of the 1810 War of Independence and 1910 Revolution, events that unleashed pent-up historical aspirations for land, freedom, democracy, and equality.

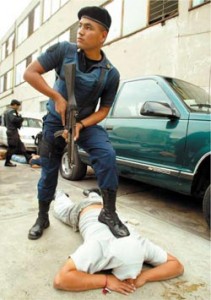

Ironically, the dirty war the Chihuahua-born intellectual so brilliantly recreated is back in force just in time for Mexico’s historic year. From Chiapas in the south to Chihuahua in the north, forced disappearances, murders of activists and politicians, attacks against journalists, and other violations of human rights are steadily mounting.

While many elements of the first dirty war endure, new ingredients fan the flames of the second one. While Washington’s Cold War was the banner for state-sanctioned violence during the last century, Washington’s so-called drug war is the ideological cloak for today’s repression.

Many regions of Mexico are immersed in low-intensity wars that coincide with a growing state intolerance toward labor and social movements. Examples include the beatings of fired utility workers by members of the Federal Police, and ongoing counterinsurgency operations against resurgent guerrilla movements of the left.

The mother of Mexico’s human rights movement and founder of the Comite Eurkea, Mexican Senator Rosario Ibarra de Piedra, compared ongoing events to the dirty war of decades ago, when her young son Jesus was detained by Mexican security forces and disappeared.

According to Ibarra, Calderon’s drug war and the criminalization of social protest are driving a new dirty war. In a recent Mexico City speech, the legendary human rights advocate called on Mexicans from all social movements to close ranks and defend one another.

“We demand commitment and decision of struggle to change this situation,” she said. “We call out for nobody to remain indifferent to the pain of so many people.”

Frequently, it is difficult to know where one conflict commences and another finishes, or where the murky underworld starts and the above-ground political system ends. Time and again, former or current members of the security forces are implicated in gangland activities. According to the Notimex news agency, Mexican Defense Secretary General Guillermo Galvan recently admitted to senators that 15,000 ex-soldiers had been arrested for crimes.

An illustrative case is in the southern state of Guerrero, where narco-violence, rebel uprisings, long-running political feuds, and historic social conflicts brew in an explosive stew. With more than 600 people still missing from the 1970s state repression, Guerrero was ground zero of the first dirty war. Now, the chronically impoverished state is a strategic front in the latest one.

The Bloody Beaches of Paradise

This month’s pitched battles and narco-executions in Acapulco and other regions of the state left 58 people dead from March 13-15 alone. Yet the murders racked up that weekend are but a sampling of the bloodshed that extends across Guerrero. The violence involves competing drug cartels, paramilitary groups, Mexican security forces, and several armed rebel organizations, including the Revolutionary Army of the Insurgent People (ERPI).

Last May, the ERPI’s Commander Ramiro gave a press conference to Mexican reporters in which he revealed years of clashes between the guerrillas and “narco” paramilitary groups. Reputed to enjoy a popular following, Ramiro was mysteriously gunned down in the remote village of Palos Grandes last November.

Hercilia Castro, a human rights activist with Guerrero Network of Non-Governmental Organizations, helped document the murders of three brothers in the mountain village of Puerto Las Ollas last November. Alejandro Carcia Cortes, 19, Bertin Garcia Cortes, 18, and Rogelio Garcia Valdovinos, 15, were shot and given the classic coup d’ grace.

“This really affected me personally. I was moved by the pain of the mother who told me how she found the bodies of her sons,” Castro said. “The boys were the joy of the community. They were among the most lively. You know how there is always someone that stands out?”

Castro said multi-layered conflicts pervade the isolated, high mountain communities of Coyuca de Catatlan and Petatlan. Land for drug cultivation, roads for contraband smuggling, and trees for illegal timber are prize commodities coveted by drug cartels backed by paramilitary groups. The residents, Castro said, could be in the way of ambitious forces seeking to cleanse and take control of the region.

Reached by dirt roads that become impassable during the rainy season, Puerto Las Ollas is like many rural communities. No health clinic exists, and only one teacher is available to teach students of all ages. Raids by paramilitary groups and soldiers make the men afraid to work their fields, Castro said. “The misery of the population is palpable,” she added.

Nationwide, Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission received 3,399 complaints against the military from 2007 to the end of 2009, including allegations of rapes, homicides, arbitrary detentions, and tortures, according to Human Rights Watch. In a recent report, the non-governmental group noted that only three personnel were initially found guilty of human rights crimes, including a soldier who received a nine-month sentence for the shooting death of a civilian at a military checkpoint.

The spike in human rights violations paralleled Washington’s $1.3 billion Merida Initiative that provides training and equipment to security forces in Mexico and Central America. Currently, officials in the United States and Mexico are laying the groundwork for Merida 2.

Violence Mars an Election Pre-Season

|

| The onset of elections in Mexico has meant more killings. |

Leading up to the 2011 state elections, a new surge of politically-tainted killings is jarring Guerrero. In February, four leaders of the center-left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) were gunned down in different parts of the state: Jose Luis Sotelo, Santana Rayo Chamu, Claudio Hernandez Palacios, and Antonio Bahena Nava. Quoted in El Sur, longtime Guerrero PRD leader Rosario Herrera stressed that 28 leaders of her party have been killed in Guerrero since 2005. Last year, the PRD coordinator of the Guerrero State Congress, Armando Chavarria, was assassinated before he could launch his widely-expected bid for the governorship.

Since its founding in 1989, the center-left PRD has been a frequent target of repression. A founder of the PRD in Zihuatanejo, Obdulia Balderas recalled how the state government repressed the new opposition party that was protesting electoral fraud, by killing and injuring protestors at the international airports of Acapulco and Zihuatanejo.

Returning from a Mexico City visit, Balderas remembered visiting fellow party members in a Zihuatanejo hospital. “There was never any justice,” said the retired school teacher.

While the early wave of repression against the PRD was politically motivated, the reasons for the most recent round of violence against party members are less clear, according to Balderas.

Even as the death roll of PRD members increases, the earlier slaying and disappearance of more than 200 PRD militants in Guerrero, especially during the formative years of the political organization between 1989 and 1996, remains unsolved.

To the dismay of Guerrero residents, human rights violations soared after a popular reform candidate supported by the PRD, former Acapulco Mayor Zeferino Torreblanca Galindo, was elected governor five years ago. Violence increased during a period when the PRD, a party that rose from the ashes of the dirty war under the banners of justice and democracy, held not only the governorship but the state legislature and many municipal governments as well.

“This represents a throwback to the dirty wars of the 1970s,” said Hercilia Castro. “It is a small taste for public opinion of how Guerrero is the example of the eternal dirty war, of how repression takes place. This is a slice of what we are going through in the entire country.”

Many recent killings have been tied to the underworld wars, but citizens of all stripes have been among the victims. A grassroots organization, the Committee of Relatives and Friends of the Kidnapped, Disappeared, and Murdered, was organized to press for justice.

On the third anniversary of the disappearance of Jorge Gabriel Ceron, a Chilpancingo architectural student and community activist who was kidnapped by an armed commando in March 2007, the citizens’ committee issued a statement:

“We have underscored how so-called organized crime is part of the state, of private enterprise, and of the political class, which in the final analysis, is responsible for the public insecurity, corruption, terror, and impunity in which the citizenry in general lives, and of which Jorge Ceron, his family, and all of us have been victims.”

Originally trained by the Mexican Army in the 1990s, paramilitary groups are resurfacing in the southern state of Chiapas as well, where recent attacks have been registered against pro-Zapatista communities and other opposition organizations.

The dirty war intensified after President Calderon took office in late 2006. The next year, Popular Revolutionary Army leaders Edmundo Reyes and Gabriel Cruz were arrested and disappeared in Oaxaca. They have not been found and are feared dead. In 2008, two leaders of the indigenous Organization for the Future of the Mixtec People, Raul Lucas and Manuel Ponce Rosas, were kidnapped, allegedly by police officers, and murdered in Guerrero. Late last year, Mariano Abarca, a prominent anti-mining organizer in Chiapas, was shot to death in Chicomuselo, where farmers had waged a struggle against a barite mine run by the Canadian-Mexican firm Blackfire Exploration, Ltd.

The recent disappearance and murder of activists closely followed the failure of the administration of former President Vicente Fox to successfully prosecute government officials, including ex-President Luis Echeverria, implicated in dirty war crimes, and the dissolution of the special prosecutor’s office in charge of probing the dirty war by the Calderon administration.

The Drug War as Cover

The drug war serves as a convenient cover for the new repression. In Ciudad Juarez and the state of Chihuahua, numerous activists have been murdered or disappeared since 2008, the year when a war erupted between two competing cartels and the army was dispatched to ostensibly quell the violence.

Among others, the victims have included anti-kidnapping activist and Mormon community leader Benjamin LeBaron, farm protest leader Armando Villareal, university professor Manuel Arroyo, human rights activist Alicia Sainz, street vendor leader Geminis Ochoa, and Josefina Reyes, a former PRD elected representative and outspoken army critic. No one has been arrested or sentenced for the crimes.

On March 2, Ernesto Rabago Martinez was murdered in Chihuahua City. A member of the Bowerasa Civil Association, Rabago helped defend indigenous Raramuri involved in a land battle against powerful interests in the community of Carichi. Rabago’s killing capped nearly a year of attacks against Carichi’s defenders and indigenous leaders.

In response to the Rabago assassination, the Chihuhaua City-based Cossydhac human rights organization and the Women’s Human Rights Center demanded an end to the criminalization of activists, and protection for human rights defenders who the two groups said live between “commitment and risk.”

Moreover, the daily drug war carnage in Ciudad Juarez (approaching 5,000 slayings since January 2008) obscures and minimizes issues like the land conflict between long-time residents and members of one of the city’s influential families. Engaged in a court battle, residents of the Lomas de Poleo neighborhood have repeatedly complained of aggressions by armed private security guards operating under the noses of the police and army.

A recent report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights documented 128 acts of aggression against human rights defenders and family members between Jan. 1, 2006 and Aug. 31, 2009. Despite the issuance of protective orders by government officials, the aggressions continue. In recent months, several organizations defending indigenous rights in the La Montana region of Guerrero have experienced a pattern of surveillance, break-ins, and even death threats. On Mar. 18, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) issued a statement of alarm over new death threats and harassment against members of the Me’phaa Indigenous Peoples Organization.

Disclosing that several of the threatened activists had been suggested by the IACHR as witnesses in two international court cases against the Mexican state, one of which involves the alleged rapes of two indigenous women by Mexican soldiers in Guerrero in 2002, the Organization of American States’ official human rights body reminded the Mexican government that previous protection orders had been issued for the Me’phaa activists and that the government had an obligation to protect the defenders.

“The Commission also recalls that the work of human rights defenders is critical for the construction of a solid and lasting democratic society, and they play a leading role in the process to fully implement the rule of law and to strengthen democracy,” the IACHR declared.

Commitment to Human Rights Put to the Test

Almost daily, national and international rights advocates denounce the deteriorating human rights landscape in Mexico. Since the beginning of the year, a slew of critical reports and recommendations have come from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the United Nations Human Rights Committee, U.S. State Department, members of the European Parliament, and many others.

The Calderon administration’s response to the barrage of criticism has been contradictory. Though some officials readily acknowledge problems, defensiveness and political posturing are still operative reactions. Countering the U.S. State Department’s latest report, Brigadier General Benito Medina Herrera rejected the notion that the armed forces violate human rights. Military personnel, General Medina told Notimex, receive human rights training and principles from the “lowest levels” to the highest generals.

Perhaps the litmus test of Mexico’s real commitment to international human rights standards will be the Calderon administration’s response to a historic 2009 decision by the Organization of American States’ Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

In an obligatory sentence publicized last December, the Court held the Mexican state responsible for the disappearance of Rosendo Radilla, a former mayor of Atoyac de Alvarez, Guerrero, who disappeared during the first dirty war in 1974. In the presence of his young son, Radilla was picked up by Mexican soldiers at a roadblock and whisked away, never to be seen again.

The Court ordered the Mexican state to clarify Radilla’s disappearance, reform the military code of justice that shields soldiers from prosecution for civilian crimes, compensate family members for damages, and publish the entire sentence in the official government record and a publication of national circulation.

The federal government will also have to conduct a public ceremony acknowledging its guilty role in Radilla’s disappearance, and erect a plaque in memory of the man in Atoyac de Alvarez.

Radilla’s daughter Tita is the vice president the Association of Relatives of the Detained, Disappeared, and Victims of Human Rights Violations in Mexico (AFADEM), a group that has worked tirelessly for decades demanding justice for Radilla and other dirty war victims. Together with the non-governmental Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH), whose lawyers pursued the Radilla case internationally, AFADEM hailed the Court’s action as a vindication of its struggle and a positive step toward ending institutional impunity for human rights crimes.

The Court gave Mexico one year to submit a report detailing progress in complying with the sentence. Even though the Mexican government has posted the sentence on the federal attorney general’s website, it has been slow in complying with other parts of the sentence, said Humberto Guerrero, the CMDPDH’s legal director. Most importantly, relatives still don’t know Radilla’s fate, he said.

According to Guerrero, the UN Human Rights Committee raised the Radilla case at a recent New York meeting. Present for the session, Mexico’s military prosecutor told committee members that the armed forces were working on changing the military code of justice at an “opportune moment,” Guerrero said.

Compliance with the Radilla sentence, he added, will determine whether or not the Mexican government reinforces the “message of impunity” that prevails in the country.

“Failure to comply with the sentence implies that Mexico does not have the will to confront its authoritarian past,” Guerrero contended. “Mexico has a new opportunity. It had an opportunity in 2000 with Fox and the special prosecutor, and now it has one with this case.”

Kent Paterson is a freelance journalist who covers the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Latin America. He is an analyst for the Americas Program at www.americaspolicy.org.

For More Information

http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/03/08/mexico-human-rights-watch-statement-human-rights-committee

http://www.cidh.oas.org/Comunicados/English/2010/32-10eng.htm

Murder Capital of the World

http://americas.irc-online.org/am/6681

Perils of Plan Mexico: Going Beyond Security to Strengthen U.S.-Mexico Relations

http://americas.irc-online.org/am/6591

A Primer on Plan Mexico

http://americas.irc-online.org/am/5204