In 2012, the Mexican government had granted rights to 2,173,141 hectares of indigenous territory to transnational mining companies. Indigenous communities have lost jurisdiction over 17% of their lands through mining concessions in the last 100 years, not including hydroelectric projects. The majority of these concessions in indigenous territories were granted by the last two PAN governments under the Salinas government’s neoliberal mining law.

|

Number of concessions granted in indigenous territories, 2000-2012 |

|

|

Gold |

2814 |

|

Silver |

71 |

|

Copper |

25 |

This small table of recent land concessions indicates that the most profitable form of open pit mining is currently gold. In 2009, the global use of gold is spread across private investments (18%), official reserves (16%), jewelry (52%) and industrial purposes (10%).

It is incredible how the fetishism surrounding gold has wreaked such economic, social, cultural, and environmental havoc. As massive industrial mines are exhausted, gold dust or particles are collected in rock or gravel deposits. To obtain tiny volumes of the metal—a medium-depth mine yields just .7 grams per ton removed—large tracts of land must be acquired to explore precise sites of mining interest.

Industrial open-pit mining produces craters. The material removed is placed in large pools, and sodium cyanide, as the cheapest and most “efficient” compound, is used to leach the metal. After various accidents, the use of sodium cyanide in the leaching process has been prohibited in some European countries. The same European companies, however, intend to open a production plant for this highly toxic compound in Mexico. These intensive industrial processes are high risk, and can’t be both sustainable and competitive, as SEMARNAT claims. The environmental scars (including the destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity) social scars, and economic scars are long lasting. It is a model that carries high risks for human and environmental health and generates significant amounts of greenhouse gasses without providing any benefit our towns, municipalities, states, and the nation.

Most of the concessions in indigenous territories are in the exploration phase or in search of investors, while 106,833 hectares are already being mined.

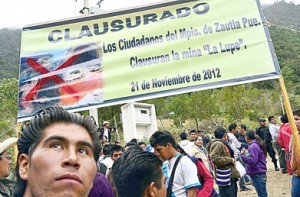

According to the mining law, the government is obligated to inform the landowners of its intention to grant a concession and inquire as to whether there is local interest in exploiting the minerals, and give “preferential” status to these local interests. There are greater instances of illegal concession in indigenous territory concessions, since international conventions for free and informed consent (Convention 169 OIT, U.N. Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Communities and the “Protocol for imparting justice in cases involved the rights of indigenous peoples and communities” in the Mexican Supreme Court) are ignored by the Secretary of the Economy.

Some concessions cover nearly all of the territories of small indigenous groups in the north of the country, including the Kiliwas, Kikapoo, Cucapas, Pimas, Guarijios, and Pápagos–all peoples that are in danger of disappearing. Groups hit hardest are the Rarámuri, (Tarahumaras), Zapotec (mainly in the central valleys of Oaxaca), Chatinos, Mixtecos, Coras and Tepehuanes, and the Nahua of Michoacán. Concessions in these territories total more than one million hectares.

What does the government handing over the country to transnational mining companies mean for indigenous groups? By 2012, the PAN governments had given 31 million hectares to these large companies. Many concessions cover marine areas, environmentally protected areas, indigenous territories, peasant communities, and ejidos. Lands are handed over often without even informing the inhabitants.

This pattern of land redistribution is happening on a global scale. Mining concessions are part of the territorial dispossession of thousands of Mexicans, transferring land to large mining consortia, mostly foreign. For indigenous and peasant communities, the incursion of this type of mining on their lands means no commons to administer, no social relations to establish, no nature to administer, no ancient knowledge systems to reproduce, no gardens to sow, no plants to domesticate.

In short, it means cultural death, generated by the collision between an industrial project of the culture of death and the implicit, regional projects of the indigenous and campesino communities over a given territory. For these communities, it is part of a serious neocolonial process, whereby jurisdiction over lands and lives, over Mesoamerican cultural relations to the land, to the ecosystems, and to natural resources including water are lost.

Original in Spanish here. Translation: Paige Patchin