It was 35 years ago when Amexco S.A. de C.V. began its infamous illegal dumping of lead-contaminated residues in Tijuana – 30,000 m3 of slag imported from California under what the Mexican government deemed the false pretext of car-battery recycling.

By the time Mexico’s federal environmental prosecutor analyzed remediation options in 1996, the U.S. corporation Alco Pacifico Inc. had acquired the liability. Mexican law mandated the return of the hazardous waste to its country of origin.

But instead, authorities let it be loaded on the train and shipped in canvas bags to the Cytrar toxic waste site in Hermosillo, where tons of it remain, in non-compliance with numerous environmental and health regulations. Environmental concerns and cancer and related death rates have soared in nearby neighborhoods.

Unanswered demands for cleanup and investigation persist to this day in both Tijuana and Hermosillo, giving rise to the filing of citizens’ complaints at the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). Meanwhile the traffic in used batteries escalates.

Hope for Reducing Exposure to Toxic Wastes

However, victims of this environmental injustice now have reasons to hope for a decline in similar scenarios that would otherwise compound the problem in the future.

Recommendations of an independent study ordered by the trinational CEC prompt the governments of Mexico, the United States and Canada to 1) bust clandestine battery-lead recovery operations, 2) raise the bar on mandatory reporting and regulations covering the legal portion of the industry, and 3) provide incentives for other industries to send dead batteries only to recycling facilities that comply with best practices.

Simply following this last recommendation would effectively eliminate the majority of shipments to facilities in Mexico for the time-being, since the so-called secondary smelting of spent lead-acid batteries (SLABs) is an industry in woeful shape in this country, with comparatively little tracking or safety enforcement, as the study revealed.

That in turn would protect the health of workers and other community members. According to the World Health Organization, 120 million people have lead poisoning–about three times the number of people infected with HIV/AIDS.

The Mexican non-profit Fronteras Comunes martialed non-governmental organizations’ involvement in the CEC-sponsored study, which also had ample input from industry, officials, and the pollutant registers of all three countries in the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The CEC released the final draft of the study on Nov. 30, for public comment. Entitled “Hazardous Trade? An Examination of U.S.-Generated Spent Lead-Acid Battery Exports and Secondary Lead Recycling in Mexico, the United States and Canada”, the report affirms the fact that there is no safe level of lead in blood. Breathing or ingesting the heavy metal poisons the nervous system, heart, kidneys, bones and reproductive organs, especially in fetuses, babies and children.

Even before the final release of the study, slated for early 2013, civil society outpaced government in putting the findings to work. A new non-governmental organization called SLAB Watchdog and its partner Occupational Knowledge International unveiled their campaign in public meetings during the autumn of 2012 in Mexico City; Lubbock, Texas; and Toronto. Their objective is for the United States to rule out SLAB exports to Mexico.

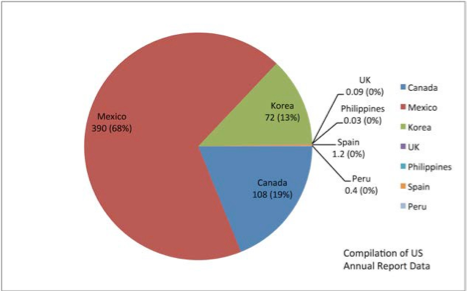

Increasingly stringent regulations on lead recovery in Canada and the United States have improved safety at their 19 secondary-smelting facilities, according to the report. However, this in turn has increased the cost of the process, fueling a 450-percent surge in exports of SLABS from the United States to Mexico, since 2007.

South of the border, “few smelters appear to have the types of controls, processes and technologies necessary to receive a permit in the United States or Canada,” the report circumspectly notes. Meanwhile, it states, the competition they represent for state-of-the-art recyclers is unfair.

Mexico moves closer to having nbso online casino reviews a pollutant register

The findings and recommendations would not have been possible without the all-important granddaddy source of environmental information–the Pollutant Release and Transfer Registers (PRTRs). These provide the focus of a CEC-driven, multi-stakeholder sector, comparability effort.

The registers, known as the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) in Canada and as the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) in the Unites States, compile the results of mandatory reporting by factories on the kinds and amounts of toxic waste they discharge and ship.

Yet even as the study proved the usefulness of the registers, it exposed Mexico as seriously lagging behind. Non-governmental organizations have been demanding for years that Mexico implement its PRTR despite corporate antagonism.

It was not until Nov. 30, 2012, the last day of Felipe Calderon’s six-year term as President of Mexico that the government finally responded to 18 years of grassroots pressure for implementation of a Pollutant Release and Transfer Register: The Diario Oficial de la Federación published a list of hazardous wastes that each federally regulated factory must acknowledge it generates.

The list, in the form of Mexican Official Standard 165, is the legal instrument to implement PRTR regulations approved in 2004.

The obligation for industries to annually register the amounts of each chemical they release under penalty of fines was slated to take effect after consideration of input received in a public comment period ending 60 days from the publication of the list.

While the announcement was a cause for hope, it also was a reminder that environment health advocates have had to toil throughout four entire presidential administrations to achieve a Mexican PRTR.

The United States started its version in response to public outcry over the secret gas discharges of the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal in 1984 that left some 20,000 people dead. Canada followed suit with its version in 1992.

In Mexico, a variety of organizations fought for and won an amendment to the General Environmental Equilibrium and Environmental Protection Law in 2001, directing the environment ministry to begin establishing the register. This made Mexico the first country in Latin America to lay the legal foundation for this landmark edifice of public access to environmental information.

Following approval of regulations, a voluntary reporting process got underway on April 1, 2005, using a provisional reporting list of 104 substances. But ever since that expired on April 1, 2007, the public reporting of toxic wastes has had no legal underpinning, proving less than useful for all practical purposes, including the comparisons the CEC seeks to make.

In a scorching statement at the CEC’s PRTR advisory committee meeting in Toronto, Oct. 30-31, 2012, transboundary PRTR advocates noted a five-year lapse during the Calderon Administration, in which the rules were “snagged” at the Cabinet level, labeling it “foot-dragging in the environmental bureaucracy.”

In a scorching statement at the CEC’s PRTR advisory committee meeting in Toronto, Oct. 30-31, 2012, transboundary PRTR advocates noted a five-year lapse during the Calderon Administration, in which the rules were “snagged” at the Cabinet level, labeling it “foot-dragging in the environmental bureaucracy.”

Organizations declaring “fervent rejection of the way the Mexican government has conducted itself in regard to the matter of establishing the inventory” were: Asociación Ecológica Santo Tomás, Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness, CIP Americas Program, Greenpeace México, and Fronteras Comunes.

When the list was published one month later, the groups congratulated themselves for breaking the barrier that industry representatives had built inside the government to slow the progress of the initiative.

“Of course, we aren’t saying this is a victory that means from now on everything will be transparent and the emissions will be accounted for, reduced, and the list enlarged,” Fronteras Comunes’ Azucena Franco noted. “But it is great news that by law they have to report.”

The U.S. version of the inventory covers 600 substances, Canada’s register covers 300. Mexico starts off with 200. According to the CEC, 57 substances are common to the lists of all three countries.

While the number in Mexico is small, non-governmental organizations in the working group that the environment ministry sponsored to devise the list determined that starting slow would be better than never starting at all, a threat they faced due to the preponderance of obstinate industry spokespeople in the group.

The period for drafting the new substance list “elapsed in a slow bureaucratic framework, only posing as a transparent process, but in truth consisting of one in which the opinions of society transmitted through NGOs in the working group for the standard and those of participants from academia were not sufficiently represented due to an unfavorable balance of forces with industry and government,” the Toronto declaration noted.

As registers are established they are constantly revised and enlarged in the northern industrial countries that were the first to employ them as a way to ensure that “what gets measured gets managed” and to make the polluter pay.

The registers are catching on globally now, with the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) helping Latin American countries to undertake them; the U.N. Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) helping eastern European countries, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Global PRTR Initiative.

One hope that remains to be fulfilled is for the 2012-2018 administration in Mexico to assume its rightful place in the international order and adopt a more proactive approach to mandatory toxic pollution reporting.

Talli Nauman is a founder and co-director of Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness, an independent media project initiated in 1994 with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and a regular columnist for the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org.

Photos and Pie Chart: Courtesy North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC)