The villas of Buenos Aires–the poorest neighborhoods in the city, self-constructed, self-defended during decades of state harassment and real estate speculation–produce one of the best publications around. La Garganta Poderosa, which means “the powerful throat”, is a monthly magazine, the expression of a group of co-ops that exalt the daily lives of thousands of people.

The villas of Buenos Aires–the poorest neighborhoods in the city, self-constructed, self-defended during decades of state harassment and real estate speculation–produce one of the best publications around. La Garganta Poderosa, which means “the powerful throat”, is a monthly magazine, the expression of a group of co-ops that exalt the daily lives of thousands of people.

“Tell me your name.”

“La Garganta Poderosa” is the only answer I hear behind a provocative smile.

“No. Your name. Your name. ”

The smile cuts the icy air that sweeps the courtyard, where hundreds of villeros (residents of the barrios) debate diverse subjects, ranging from education and negative consumption patterns to gender contradictions, and, of course, the issue that brings them all together: the urbanization of their neighborhoods. It is the third Congress of the Independent Villero Faction, the organization that unites inhabitants of the dozen villas in the capital. It comes off a two-month campout next to the Buenos Aires Obelisk, calling on the city government for answers to an almost endless list of demands.

“La Garganta Poderosa is the name we have when we speak with the media, because it”s the way to avoid personalized, commercial, or partisan cooptation. Because what we need is for the collective to grow.”Words tumble and stumble out of his mouth as if they were pushing each other–no periods, no commas, no breaks. Like those hip-hop lyrics that seem to be gasped, spit out, as if fleeing the police.

La Poderosa is a neighborhood organization that articulates 15 assemblies from the federal capital and eight provinces. The magazine is just one of several initiatives. La Garganta Poderosa prints between 12,000 and 22,000 copies per month, and reached 50,000 in the issue devoted to the World Cup. They have some 150,000 followers on Facebook.

The editorial staff works in what was a clandestine detention center during the dictatorship, the School of Naval Mechanics (la Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada), converted to the Space for Memory and Human Rights (Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos) in 2007. “We started as a magazine three years ago. It was an outgrowth of the Poderosa communication co-op, the grassroots movement born ten years ago as the joining-together of various villero assemblies, where a number of initiatives and cooperatives emerged” says a member of the magazine.

Among the cooperatives: the gastronomical Sabores Poderosos, Estilos Poderosos textiles, and the communications co-op that publishes La Garganta Poderosa.

“It”s called La Poderosa because that”s what Che and Alberto Granados” motorcycle that toured Latin America was called. They represent the struggle of our neighborhoods.”They consider the organization to be guevarista (following Che”s example), defend the Patria Grande (regional integration region), and have no party affiliation.

“We meet a lot of compañeros who may be divided at the time of voting, but we agree on gaining literacy and in organizing ourselves. Almost all of us are from the villas, sometimes outsiders support us. We identify with Che and Father Mugica,” he says, referring to the priest in the late 1970s committed to Retiro Villa that was killed in 1974 by Triple A paramilitaries.

They feel united in Corriente Villera. They practice popular education, and do things in a different way. For example, in soccer. Everyone trains together in the neighborhoods–men and women–but they agree on special rules before each game.

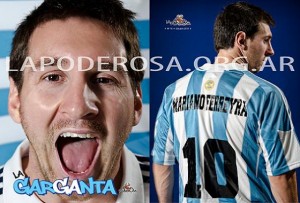

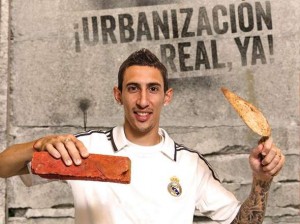

The publication is surprising for many reasons. It”s printed on glossy paper, the same type used in fashion and business magazines. The photo quality is excellent. Soccer players like Maradona, Messi and Di María (many of them villeros) appear on the covers, as do leftist politicians (Evo Morales, Mujica) and supportive rock musicians and artists. All of them Garganta Poderosa.

It is written in a special way–like hip-hop lyrics –rhyming, forming cadences that give life to almost monotone rhythms: “Detrás de las postales de las crónicas tradicionales, que siempre te muestran la mierda flotando, pero jamás se detienen en las cloacas que nos vienen negando, salimos a mojarnos bajo una lluvia torrencial, para entender cómo funciona el sistema pluvial de las favelas que rodean al Mundial.”

“Thanks to the magazine, today we are recognized in places like universities, which always devalued villero knowledge. The magazine is not an end, it is a means to fight for the urbanization of villas, which is the right to life. ” By urbanization, they mean the end of discrimination: police impunity, dirt roads, floods, state and drug-related violence, lack of schools and health facilities, air and soil pollution, contaminated water or lack of water, among the most evident. In short, poverty and inequality.

They do not want the magazine to be printed on inexpensive paper, because it would be tantamount to saying “what comes out of poverty cannot be of good quality.” 28 pages monthly on glossy paper, with 15 distribution cooperatives, one in each assembly-neighborhood, which gives kids in the villas work. “It is unanimous that it not have ads, because it is the expression of villero people, of many who gave it life.”

La Poderosa militants self-educate in rounds of conversation in the neighborhood. Their political ideas are born of practice. With the money they earn from the magazine, they take the neighborhood kids to the beach in summer, something their families could never do. Every year they bring 50 children from each of the 15 assemblies. They sell the magazine for 18 pesos outside the neighborhood (two dollars), but offer it to the villa at cost.

The magazine got resources flowing into the neighborhood: “Until three years ago the financing channels we had were the legitimate popular economic practices within the village: raffle, bingo, the festival, the choripaneada (sausage sandwich sales), the American fair, used clothes sales and selling barbecue chicken.”That is, local people”s money was circulating, but outside money wasn”t coming in. The magazine allowed the possibility of selling something outside, so resources could come into the villa. The problem is not that money doesn”t circulate, but that it doesn”t enter. “The result is amazing because the outside responded very well, much better than we thought.”

45 people work in the co-op that makes the magazine. They have already published 40 issues. And among Facebook followers, heads of the mainstream news media were detected. “They can”t say that they don”t know what happens in the villas any longer–they should say they choose not to publish it. We are in the kiosks, they called us to distribute there, and we go along with the Association of Independent Cultural Magazines,” where dozens of publications not identified with the commercial and media monopoly are grouped.

“How do 45 people agree on the cover?”

“How do 45 people agree on the cover?”

He smiles. Wavers. Gets serious:

“Sometimes we are criticized because we put a famous person on the cover, but if we didn”t, no one would be interested in reading us. We were born in this consumer society, and we didn”t choose that. We found a hole, put Messi on the cover, and it sells. But we put [a photo of him in] a Mariano Ferreyrashirt, and we do that with everyone. It”s our way of seeing things. The Maradona and Indio Solari covers were the ones that made the magazine known. It was an agreement they accepted and now Diego is with us all the way. There was a lot of discussion about the Messi cover because he wasn”t born in a villa.”

His face lights up when he tells of Messi playing with a paper online casino world map for 40 minutes for the cover photo, photographed with Julio López and Ferreyra shirts. “It”s our way of putting these issues in places where they never arrive. What we learned is that even in the worst media, there are valuable partners, that they don”t seem apathetic to us, what they do in those medias. And they were the ones that generated cracks for readers of those media to get to know us. That”s the most difficult.”

Living in the villa: death and football

Living in the villa: death and football

“In an urbanized district, Kevin wouldn”t be dead. A bronchial-spasm isn”t a cause of death, neither is a pre-heart attack, because ambulances would be able to enter. In our neighborhood, people die from fires and that wouldn”t happen in other districts. Within a year, 5 year old María died by fire. Kevin in Zavaleta died, in a meter-wide hallway. Facundo died in villa 31 because a tree fell on the roof of the house, Pascual because the ambulance didn”t enter [the villa] to get him, Rodrigo in Fátima…If we lived in a neighborhood ambulances would enter, where children are schooled…” Kevin”s memory is the most painful. He was a nine year old boy who lived in Villa Zavaleta with his parents and five siblings. On September 7, 2013 there was a shootout between two drug gangs. The police arrived and walked around, saying, “Let them kill each other.” One bullet entered Kevin”s house and killed him.

The La Poderosa assembly in Zavaleta put up a casilla for residents to report police abuse. “Si la gorra se zarpa denunciala acá” reads the mural. It”s a matter of community members supported by other community members, who have the support of a network of journalists, the Center for Legal and Social Studies, and the Office against Institutional Violence. “With part of what the La Garganta Poderosa magazine brings in, and other cooperatives in the neighborhood, a minimum remuneration for those involved will be paid, and also for further maintenance,” a community member explained to MU magazine.

“Insecurity is that they mock you in the face. That a house starts on fire and kills a family, and the firefighters come without water, and an ambulance without doctors. Or that the ambulances don”t directly enter,” states Paola, an editor for La Garganta Poderosa Zavaleta. Thus the Vecinos sin Gorra group was born. They toured all households to explain what it is, and received almost unanimous support.

Paola deserves a book. She was abused by her stepfather. Her mother was a cartonera. “I never lacked anything, but I was always missing my mom.That”s why what happened to me, happened to me.”She joined La Garganta Poderosa. She has interviewed Maradona, Joan Manuel Serrat, and other famous people. But she most remembers Félix Díaz, the Qom leader, and doesn”t believe herself to be anything special for doing this job. Her ethics of life, her history, are blows to the journalistic ego.

Paola deserves a book. She was abused by her stepfather. Her mother was a cartonera. “I never lacked anything, but I was always missing my mom.That”s why what happened to me, happened to me.”She joined La Garganta Poderosa. She has interviewed Maradona, Joan Manuel Serrat, and other famous people. But she most remembers Félix Díaz, the Qom leader, and doesn”t believe herself to be anything special for doing this job. Her ethics of life, her history, are blows to the journalistic ego.

In a climate of violence and despair, sports are a way out. Sport in villas is synonymous with soccer. But here also, La Poderosa differs from commercial sport: “Before every game, an assembly is made and rules for that game are defined. As we saw that women were not being passed the ball, we decided that women”s goals were worth double. And that started the debate about whether that”s discrimination. Now when women play better, no one tells them their goals count double; it would be an insult.”

They view it as solidarity soccer, but they play hard. “We learn to respect our own rules. We play without a referee because it”s not needed; if we are honest we don”t need a judge. If someone fouls, the players themselves call it. Before the game, a moderator is named, who stands outside [the field]. And if the game has to be stopped because something bad happened, it stops, and we talk. It was difficult to set this way of running things, but now it”s everywhere. Everyone, to the Qom indigenous community in Boedo, plays on our league. They are all grassroots organizations.”

During World Cup, they spent a month in the Santa Maria favela of Rio de Janeiro. They played a game with Cidade de Deus to demystify the stigma, and ended by shouting “the people united.” They went to the favela because they wanted to unite their love of soccer with their criticism of FIFA and repression during the World Cup. “As with the soldiers used the “78 Cup (in Argentina) to cover crimes against humanity, we use the World Cup as a showcase for what is not said.” They could talk for hours about soccer and that incredible experience in the favela. “Never was a country home to the World Cup. The Cup was not played in Brazil, but inside that FIFA bubble, with FIFA culture, FIFA prices, FIFA security, and FIFA racism. We had fun with the rivalry. The people of the favela, screaming for Argentine goals. What the media does is something else.”

It”s inevitable to come back to the beginning: anonymity, the dissolution of each individual in the collective, at least outwardly. A principle of collective construction they didn”t learn in any manual but rather, like everything, by sharing in rounds of discussions and, above all, the ordeal of confronting the police.

“Calling all of ourselves Garganta Poderosa, it”s like the Zapatista facemask. When they individualize you, you became a piece of a puzzle that you yourself don”t control, thus destroying the entire collective. In the barrios, police individualize a person from the whole group, and then it is easier to destroy. With us they couldn”t, because we prevent individualization. While the media circus writers aren”t villeros, we do not want to be actors in that circus.”

Simple words for hard things. As with the ego, commonplace among journalists. “We have to tame our own ego. That”s the work of the collective, and of each and every one. It”s difficult, in the midst of the health needs, and the troubles among us. But all of the fighters we admire ended up dead or tortured. That gives us strength to go on. ”

In Zavaleta, older women do “people”s control of the police” and security forces to fulfill their obligations. To do so, they built the guard house. They became Vecinos sinGorra with its People”s Control of Security Forces.

“It must be very controversial, risky,” I search with caution.

The answer is a blow: “When things gets comfortable, something is wrong.”

Raúl Zibechi is international relations editor at the magazine Brecha in Montevideo, adviser to grassroots organizations and writer of the monthly Zibechi Report of the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org

Translation: Paige M Patchin