One month ago today a burly, middle-aged reporter set out from the offices of the news weekly Riodoce that he co-founded some fourteen years ago, walking toward his car at high noon. In the preceding days, the internationally renowned journalist had admitted to people close to him that he felt anxious about his safety.

One month ago today a burly, middle-aged reporter set out from the offices of the news weekly Riodoce that he co-founded some fourteen years ago, walking toward his car at high noon. In the preceding days, the internationally renowned journalist had admitted to people close to him that he felt anxious about his safety.

He had just penned what would be his last column that morning when his life was brought to an abrupt end by two unknown assassins using a silencer. The killers reportedly dragged him from his car and shot as many as 13 rounds into his body, by day. in the middle of a city street.

To the shock of the nation and his many readers, fellow journalists and admirers in Mexico and abroad, Javier Valdez Cárdenas was murdered openly in his hometown of Culiacan, Sinaloa– a capital city notorious for being located in the middle of a fierce drug war.

The reason behind the shock was not that hit men struck a journalist. There have been eight journalists assassinated in Mexico this year alone, a record-breaking statistic that has propelled the nation to the top of the list of the most dangerous countries in the world in which to practice journalism, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The reason for the shock was also not because Valdez covered a safe beat. He didn’t. His reporting, along with others at Riodoce, focuses on the politics and on-the-ground realities of the drug war.

The reason the murder shocked so many people out of complacency is that Valdez was arguably the most recognized journalist yet to have been assassinated in Mexico’s long and sordid history of impunity.

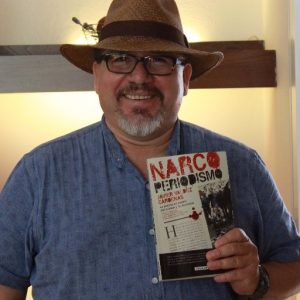

Valdez was a prolific and widely read author. In the span of his 50 years he published seven books and earned numerous national and international awards. Riodoce has been an invaluable news source due to its incisive reporting and commentary on the drug war, a rarity in the region where many other news outlets have shuttered because of safety concerns. Valdez was also the Sinaloa correspondent for La Jornada, a nationally-distributed daily.

Previously, Mexico-based journalists believed that a high profile gained by publishing in high-circulation outlets or racking up awards would serve as a measure of protection. Several years ago when I met Valdez and asked him about reporting on sensitive drug war-related material, he advised me to seek outlets with as major a circulation as possible. Many journalists thought 2017 couldn’t get any worse, following the murder of the La Jornada correspondent in another drug war-infested area (Chihuahua) this past March, and now they were confronted with a nightmare scenario: Who could truly be safe if they could assassinate someone as famous as Javier Valdez in broad daylight?

Marcos Vizcarra, a reporter for the newspaper Noroeste in Culiacan, told the Associated Press that reporters across the country “don’t know what to do,” following the Valdez murder and felt, “nervous, unsettled.”

Despite the widespread outcry that came in the aftermath of Valdez’s assassination, authorities have not made a single arrest in the case. An examination of official developments and the concerns behind those who most closely monitor journalism safety and the lack of justice in Mexico helps shed light on where matters have gone and how they are expected to progress.

“We Had Never Interviewed a Drug Lord”

Javier Valdez was born, raised and seasoned as a journalist in his native Culiacan, Sinaloa. Sinaloa serves as the operating hub of the world’s largest and most powerful drug cartel, the Sinaloa Cartel, which produces and transits methamphetamine, marijuana and heroin almost exclusively bound for the U.S. market. Unsurprisingly then, Sinaloa also breeds and hides many of the country’s most powerful drug lords.

Valdez’s path diverged from that of other journalists covering the narco beat who aspired, and sometimes succeeded, to venture into the highlands of Sinaloa to make contacts with and interview drug lords. Instead, Valdez wielded his craft from the bars, cafes and street-side seafood stalls of Culiacan. He often left out names, dates and places, but the information coming from Valdez’s columns were chock full of on-the-ground information based on sources cultivated over many years of street-beat journalism.

Ismael Bojorquez, the other co-founder of Riodoce and Valdez were both there when someone hurled a grenade into the offices of Riodoce in 2009. Miraculously, no one was hurt.

This year, however, Valdez did something different. He interviewed a drug lord. When an important Sinaloa cartel representative acting on behalf of a kingpin whose importance had recently risen came knocking Valdez decided to do the interview.

“We had never interviewed a drug lord. We did it now and it cost us big,” wrote the cofounder Bojorquez, following Valdez’s killing.

In what was probably the most embarrassing moment for any Mexican President in recent memory, on July 15, 2015, Sinaloa cartel and drug kingpin leader Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman escaped from prison through a multi-million dollar tunnel nearly a mile long that he built in captivity. This being the second time that Guzman escaped, the international humiliation forced a heightened effort to recapture him. Less than half a year later he was caught, but not before he gave an interview to Sean Penn that was published in Rolling Stone. This past January, just a year after El Chapo’s recapture, he was extradited to a prison in New York City, where he continues to be held.

Guzman wielded absolute power over the cartel he led, matched only by his partner, Ismael “Mayo” Zambada. It was not long before Mexican news outlets started reporting on a power struggle between “El Chapo’s” right-hand man Dámaso López Núñez (nicknamed “El Lienciado”) and Chapo’s sons, including one particularly violent incident in Tijuana this past February, among others. López sent a representative to Riodoce‘s offices to dispel notions of him being an enemy of El Chapo or his sons.

“Chapo’s sons found out that we had interviewed Damaso and they pressured Javier (Valdez) not to publish the story,” wrote Boroquez in his column after the assassination of his friend and coworker. The paper denied the request. Boroquez said the representative offered to buy up the entire edition, but that was also denied. Valdez also went on to publish about the incident for La Jornada.

Like in the gangster movies from the Al Capone era, as soon as the batches of weekly newspapers were dropped off at newsstands throughout Culiacan, they were snatched up by cars following close behind the delivery trucks. The entire print run was bought up before nearly anyone else in Culiacan could even read it.

This was an unprecedented action and Valdez knew something was up, and stated as much to the Spanish daily, El Pais. He described the situation as “fucking hot.”

Prompted by advice from his friend and colleague, Carlos Lauria, the program director of the Mexico chapter of the Committee to Protect Journalists, Valdez left Culiacan for two weeks. Then on May 2 the authorities arrested López in Mexico City. Valdez returned to Culiacan to continue his life’s work in his native city and longtime stomping grounds.

“When I visited Culiacán last week to attend Javier’s funeral, many of his colleagues said they believed there was no longer any immediate danger to Javier and other reporters [following the arrest of López],” wrote Lauria in an op-ed for The New York Times.

But that assumption was a mistake. Drug kingpin arrests often destabilize the cities where they take place. Lauria also wrote that Valdez spoke to him of continued concerns following the arrest and his decision not to speak publicly about cartel-related violence.

Presidential-Led Reforms Fail to Crack Impunity

Before Valdez was killed in Culiacan, the murder of La Jornada and Chihuahua-based correspondent Miroslava Breach on March 19 sparked demonstrations of journalists calling for protection and justice. President Enrique Peña Nieto launched a series of initiatives to reform protection services and attempt to prevent additional journalist killings.

Following a meeting by a visiting delegation from the Committee to Protect Journalists, Peña Nieto announced measures on May 4 to combat impunity. He promised to refund a federal protection mechanism that was slated to end by October of this year.

The federal mechanism’s roots date back to 2012 when it was first started as a program called the Federal Mechanism for Protecting Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. Services included providing journalists under threat with police escorts, surveillance cameras, and even portable panic buttons to alert authorities of an emergency or an attack. However, many journalists complained that none of these measures were effective in helping them remain protected an in some cases they hindered them in being able to carry out their jobs.

Data from the program reveals a dark side of the narco-state: journalists fear violent reprisals from public officials as much as from any other sector. The Washington Office of Latin America (WOLA) and Peace Brigades International found that of 316 requests for protection, 38% of the alleged aggressors were public servants—the largest single group of attackers.

Peña Nieto also promised to replace Ricardo Nájera as the lead prosecutor for Crimes Committed Against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE). Since 2010, FEADLE has only managed to achieve three convictions and has often refused cases, while a recent investigation by Reporters Without Borders found that the program did not have the necessary resources to secure the safety of journalists, and even more damning, lacked the “political will” to do so.

According to Edgar Corzo Sosa, a Mexican official and inspector general with Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission, conviction rates for journalist killings hover around 10 percent. Of the 114 journalist murders that have occurred in Mexico since the turn of the century, the special prosecutor’s office has investigated just 48 since 2010.

“To be a journalist in Mexico seems like more of a death sentence than a profession,” wrote Tania Reneaum, the director of Amnesty International Mexico, in a press release. “The continuing bloodshed that the authorities prefer to ignore has created a deep void that is damaging the right to freedom of expression in the country,” added Reneaum.

Attorney General Raul Cervantes Andrade appointed Attorney Ricardo Sanchez Perez del Pozo as the new head of FEADLE.

“He will review each case currently under investigation, maintain permanent contact with all organizations of civil society and journalists, propitiating a permanent and transparent dialogue with society and reinforce coordination with authorities from the three levels of government,” the official statement read.

These actions happened before the Valdez killing, prompted by the prior assassinations of the year and civil society pressure. In addition to the demonstrations, the Committee to Protect Journalists met with the president and other officials and released a searing report entitled, “No Excuse: Mexico Must Break Cycle of Impunity in Journalists’ Murders.” The international organization released the report at another drug war-torn area–the eastern port city of Veracruz in what the CPJ dubs as the most deadly region for journalists in the Western hemisphere.

After the Valdez killing, the government offered a reward of up to 1.5 million pesos ($83,000 USD) for information leading to the arrests of those responsible for the murders of five of the Mexican journalists killed this year, including Valdez, as well as an attempted murder of a sixth journalist.

Journalist advocates remain skeptical of these measures, especially in light of the failure to make arrests and prosecute in the cases of the eight journalist assassinations this year alone. In this vein, Lauria told PBS that “any reforms that Mexico decides to carry out are going to be impossible if journalists continue to be killed with total impunity.”

Journalists Take the Initiative

Many journalists have little faith that the reward or the Mexican government’s reforms will make them safer. They organized a conference in Mexico City this week and expect thousands to attend. More than 50 national and international media organizations have come together with about 360 journalists in a group called the Journalists’ Agenda. The group’s web site vows to construct “an agenda with short and medium-term goals to protect journalists,” in light of a “context of systemic violence against journalists.”

Mexican journalists, usually a disperse bunch, have risen up since the murders of Beach and Valdez. Foreign governments have joined journalists, and human rights groups and freedom of expression watchdog organizations to call the Mexican government’s attention to the urgent situation. The president has promised to directly address their demands.

Will the promise be kept? Mexico-based journalists aren’t holding their breath. But one thing is certain–society and especially organized journalists are demanding protection and an end to impunity louder than ever before.