San Salvador is a chaotic city of guns. The country is fascinated with “security” and arms. Men with guns – handguns, rifles, semi-automatic machine guns – guard everything from banks to shoe stores to ice cream shops. Almost immediately after arriving in the city, the country’s liberal gun-ownership policy and obsession with security is evident in every crowded plaza. Residents say they are protecting themselves from gang violence.

San Salvador is a chaotic city of guns. The country is fascinated with “security” and arms. Men with guns – handguns, rifles, semi-automatic machine guns – guard everything from banks to shoe stores to ice cream shops. Almost immediately after arriving in the city, the country’s liberal gun-ownership policy and obsession with security is evident in every crowded plaza. Residents say they are protecting themselves from gang violence.

El Salvador cobbled together a gang truce in March 2012 between the infamous Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 gangs. For more than a year, it succeeded in reducing violence. The day after the truce began, homicides dropped from about 15 per day to four.

But the numbers are up again, and some – including the U.S. government – say the truce was “bought” and any dealings with gang members is equal to dealing with terrorists. Gang members insist the truce has been compromised by corrupt government officials who don’t want to see peace in El Salvador.

The March 9, 2012, truce is based on five points:

- Reducing all types of violence: shootings, rapes, kidnappings, etc.

- Stopping gang actions against the military

- Stopping action against the police

- Stopping action against prison custodians

- Avoiding – at all costs – civilian causalities

“Within hours, the truce was so effective it was hard for some people to believe,” says Raul Mijango, a former businessman and one of the main truce facilitators whose current job is to strengthen communications between gangs to help decrease the violence. But the recent upswings in homicide rates that have brought them back to pre-truce levels have puzzled Mijango and some gang members who say they have been sticking to their agreement. They think the increase in murders is due to sabotage.

“Some people don’t want to see the truce be successful. There is a huge network of 400,000 people who live off the violence and the business of the gangs. There’s a $7 million market for guns here. Violence is lucrative,” Mijango notes.

The El Salvadorian fixation with arms and private security agencies is rooted in real problems, but some say adding more armed guards to the country won’t resolve the bloodshed. The most densely populated country in the mainland Americas, El Salvador has been rocked by civil war in the 80s, recent natural disasters, crippling poverty and intense gang warfare. It has the second highest murder rate in the world, estimated at 11 to 17 murders per day in 2011 for the country of just over 6 million people. Citizens attribute the ongoing violence to gangs and corruption, but the subsequent obsession with armed security guards has not helped lower the murder rate.

More Bilateral Support Needed

The United States has been open about not supporting the gang truce, even in the face of its apparent initial success. Although the U.S. government has pledged more than $91 million to fund security programs in El Salvador, none of the funds are to be used for programs related to the gang truce. The money is part of the 2011 bilateral Association for Growth agreement, and is slated to be used for improving the clogged judicial system and for anti gang-recruitment strategies. The U.S. has also labeled the Mara gang as a transnational criminal organization since the truce came into effect. Mijango says the lack of U.S. support is simply undermining the truce.

“We are taking responsibility for the violence that developed in the U.S.,” said Mijango. “If the U.S. doesn’t want to help us, than at least don’t harm the process. We are trying to fix our own problem.”

Mijango says the truce needs support – both financial and social – to help with gang rehabilitation programs and to allow former gang members back into a society that shuns them. He estimates there are about 60,000 Mara gang members in El Salvador, with about 10,000 in overcrowded jails, and there is an urgent demand for rehabilitation programs.

He points out that those most suited to helping decide how to help gang members re-enter society are gang members themselves involved in the truce, but that they are cut off from funding from the U.S. He says the U.S. government should take responsibility for the spread of the gangs in El Salvador, since they were born in Southern California in the 60s and 70s. The gangs spread to Central America after tens of thousands of gang members and criminals were deported back to war-torn El Salvador starting in the late 80s and early 90s. Mijango says about 30,000 people are deported to El Salvador from the U.S. annually, most of whom are criminals.

One of those deported criminals who joined the Mara gang in Los Angles is Beto, a 43-year-old Mara leader. Beto (a pseudonym) moved to Los Angeles with his family when he was 9 years old, and was recruited into the Mara gang when he was 12. He now has teenage children living in LA, but since he was deported in 2002 he hasn’t been allowed back. Beto says he agreed to help facilitate the gang truce when he was in jail in El Salvador in March 2012.

“The peacemaking process is not easy. We understand that our country is in chaos. Why? Because of us. And we understand we need a change,” said Beto, who unlike fellow gang members famous for their extensive facial tattoos, just has a small “Mara” tattoo on his forearm.

_______________________________________________________________________________

“We understand that our country is in chaos. Why? Because of us. And we understand we need a change,” said Beto, Mara gang leader.

________________________________________________________________________________

“We turned in our guns. We stopped recruiting. The murders fell to 4 a day from 17.” He says the increase in murders is a way for critics to discredit the truce but as far as he knows, the gangs are upholding their end of the deal. “For a gang member, your word is the most valuable thing you have. It comes first. If you say you won’t do it, you don’t do it.”

Big Crime is Big Money

Beto says people with influence, including Salvadoran and U.S. politicians as well as those who make money off the security industry, don’t want to see the truce succeed. “The security industry makes a lot of money; people make money off the violence. Guns are everywhere.”

He says the rumor that the gangs turned in nonworking guns is false, and that more than 80 percent of the arms turned in were viable. Beto points out that since the gangs turned over their arms, the security forces are now the most armed entities in the country, along with the police.

Beto attributes the upswing in homicides, which critics point to as a signal that the truce has failed, to increased fighting among smaller gangs such as La Mirada and La Maquina, who are not part of the truce, and to youth who claim to be part of the Mara and Barrio 18 gangs but are not. He also says the security industry is arming the smaller gangs and paying them to keep antagonizing the Mara and Barrio 18 gangs. Another criticism of the truce is that the peace facilitators are still in the gangs. Beto believes remaining in the gang is essential to facilitating the truce, and that if they are out of the gang, they can’t intervene. “How do we tell the thousands of gang members what to do if we are apart from them?”

Both Beto and Mijango say the truce is not only about stopping the violence, but also about improving life in El Salvador. All of the initiatives require financial support. Many of the initiatives involve strategies that could be funded by the $91 million U.S. aid package, such as community centers and after-school programs, but Mijango says organizers working with gangs can’t move ahead with these ideas if the money is only to be used for programs that are not linked to the gang truce and those involved in it.

Beto says the block on funding is absurd. “There is nothing for young people to do. Parents work sun-up to sundown, they are not to blame, they bring food home. But kids need something to do. There are things that cost money, but if the parents don’t have money, what do they do? The kids are on the street, and they get involved in gangs,” he said. “The kids in El Salvador are fans of the gangs … because they have nothing else to do.”

Pact for Peace

Although the peace pact has seen criticism both from inside and outside the country, Beto and Mijango say the gang leaders, facilitators, and gang members on both sides will continue to uphold the truce. Currently, Mijango says there is a new pact on the table to involve all municipalities throughout the country in progressively improving the lives of their citizens. The “Pact for Life and Peace” is comprised of five points:

- Reaffirm the original truce of non aggression

- Reduce or eradicate all types of crime: robberies, rapes, kidnappings, murders

- Voluntarily turn in guns

- Allow free transit of people throughout the country

- Support local social organizations

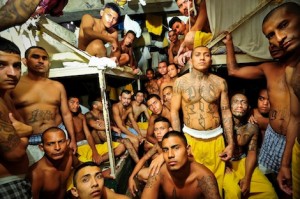

Mijango says a big part of the “Life and Peace” pact is reform of the country’s notoriously inhumane prisons, where he says 30,000 prisoners are packed into jails with the capacity of 8,000. “There’s no water, no electricity, no place to sleep, no medication,” says Mijango. “We are paying for our crimes, but they shouldn’t treat us like animals.”

Both men say the population is resentful of gang members, but the end goal here is to allow people to re-enter society and to stop violent crime. The huge network the gangs have worked with to become such a powerful international force could be turned around, says Mijango.

“Converting this huge network to do good things could be the best story of our country, ever.”

Yasmin Khan has worked as a journalist in New Mexico, Mexico and Bolivia. She now lives in Baja California Sur where she works on water supply and treatment projects in communities. She is a frequent contributor to the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org