The broad student movement that won Chile’s alamedas – with demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of young people and the occupation of dozens of secondary schools, demanding changes in the education system – has sedimented in the creation of some thirty self-managed education initiatives in working-class territories.

From its first steps, the movement hoisted the banner of “free, quality public education,” meaning that the state should take charge of making that a reality. Most continued in the streets with the same demands and requests. But since 2011, another sector [of the movement] has, with the reform proposal to modify the system inherited from the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, opted for institutions, where they became encrusted. Now it appears that the reform is so limited that it does not suit the majority of students, nor much of the faculty. But in the latest demonstrations, a sharp weakening of the movement was visible. On Sunday, September 4th, a student movement called by the “indebted to study” brought together just three thousand people, when months ago the marches were massive.

The education movement has branched into three strands. Those who gambled on being in government, with the Communist Party and Camila Vallejo at the head, suffered heavy fatigue. The radical groups won the principal university centers, such as CONFECH (Confederation of Chilean Students) and ACES (Coordinating Assembly of Secondary Students); they are committed to the fight in the streets to make demands on the government. Perhaps the fatigue suffered by these two sectors indicates that the statist dynamic is a dead end.

A new actor appeared in 2011, when the movement exploded with millions in the streets. They are those who bet on working outside institutions, but also on escaping the dynamic of petitioning the state. Building educational autonomy implies giving everything to the effort. They have put very diverse skills and experience into practice, with contradictions not easily resolved.

Communal public school

In a mansion in central Santiago’s Franklin neighborhood, the Communal Public School (Escuela Pública Comunitaria – EPC) has been running for three years. It is one of the most powerful initiatives of the education movement. The kitchen, large like those of campesinos, seems to be the main office where debate happens and decisions are made. Half of the twenty teachers are women, averaging between twenty-five and forty years old. They sum up the strengths and contradictions of those who want to do something outside of state institutions.

The initiative started from a group of teachers dissatisfied with their work, and education students who participated in the movement since 2011. They created the Diatribe Collective, which publishes a magazine of the same name, “for a militant pedagogy.” Participation in self-managed schools for several months, by the alliance between teachers and students, played a cohesive role in the Collective.

Two main objectives were proposed: the re-appropriation of educational spaces by educational communities and the formation of critical, conscious, and committed subjects, to motorize social change.[1] They claim to be part of the traditions of the rationalistic schools of the Chilean Workers’ Federation in the first decades of the twentieth century; the educational experiences in seizing urban land in the 60s and 70s; and “self-education” led by working class sectors in recent history.

Creating this kind of education involves the territorialization of school space by the educational community. The ineluctable reference is to Brazilian Paulo Freire and other authors of the call to “critical pedagogy,” but also to experiences in education in movements like the landless movement in Brazil, the Zapatistas, or the people’s high schools in Argentina.

The million dollar question is how a school self-managed by teachers, students, and local people – through “community assemblies,” which elaborate their own design, or “emergent regionalized curriculum”- should be financed. The answer given is that the state must do so through direct transfer of resources that will be administered by the school. They also propose the creation of cooperative units capable of generating revenue in the territory to sustain the school. This has been the main point of friction between EPC members, and it is that which could derail the project.

In those three years the school trained two groups of young people and adults, who completed their studies and did well enough to obtain certificates based on content decided by the state. This is the second problem, as the scarce funds they receive come from students passing examinations. It has led them to wonder if they are really an autonomous school or are simply “alternative state collaborators ” with a practice “perilously close to welfare.” [2]

The questions running through the assemblies are as realist as they are ruthless. Are we mere collaborators of the state, as executors of public policy? Are we really, in our school, prefiguring the society we want to build? Clearly they do not have answers, perhaps because, as they say in an internal text, self-management cannot be a way to obtain resources, but rather “a way of life.” They know these contradictions could fracture the teaching team, but for now, they keep going.

From hip-hop to autonomous education

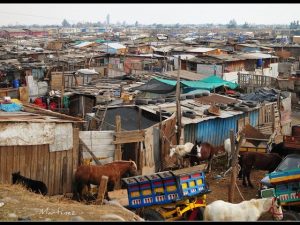

San Bernardo is the last commune in the south [of Santiago], where the city begins to be confused with the countryside. We reach a village called Los Areneros, although there seems to be disagreement on the name. Some referred to as “those at the end,” and others “those of the encampment”. The truth is that it began in 1986 after the Maipo River swelled, when the municipality decided to move those affected to this place.

San Bernardo is the last commune in the south [of Santiago], where the city begins to be confused with the countryside. We reach a village called Los Areneros, although there seems to be disagreement on the name. Some referred to as “those at the end,” and others “those of the encampment”. The truth is that it began in 1986 after the Maipo River swelled, when the municipality decided to move those affected to this place.

The neighborhood was born as an irregular and informal settlement. Three decades after those floods, single-story houses predominated: self-built by families, many of them wooden with a loft to house the children. Although the community members removed the homes of cardboard and metal sheets in favor of more solid and durable materials, the population does not hide its poverty nor the social and spatial marginalization it suffers, far from the center of Santiago.

A spacious house with a wooden front sports a large sign: “Our communities assume control of education in their territories.” It is a mansion taken hold of by the COPLA collective, a group of young people who manage a garden for preschoolers, a community radio station, a graphic workshop, a library, a garden, and lounges for activities open to the neighborhood.

The collective’s origin is very different from that of other groups of the social movement for education. They organized around rap music and hip-hop culture. Around 2009 they were setting up speakers on the street to breakdance, generating links with community members. Over the years, they began to recover spaces for community life, courts and fields, plazas, and social venues. In 2012, they were still rapping on the street, but decided to start outdoor educational workshops.

One of the rappers recounted his experience in the first COPLA bulletin. He carried out a breakdance workshop with thirty students, from twelve to eighteen years old. “This allowed for taking them a little bit out of the environment that surrounded them, showing a distinct culture that relates to discipline, dance, humility, and a little social conscience transmitted in classes.”

While rehearsing dances, values such as teamwork and the need to organize appear. They consider hip-hop culture a mode of education and, above all, of collective self-education in the conditions of a poor and marginalized neighborhood, where kids suffer from overcrowding, violence, and living alongside drug trafficking. The kids enjoyed it, and came out excited about the desire to experiment and learn.[3]

The biggest leap forward came in 2014 when they began popular education workshops, continued with breakdance workshops, and added another workshop, a theater one for little girls and boys. During the workshops, the children decide what they want to come next and how, which becomes an educational process that seeks to “resolve situations in the most participatory – and not authoritarian – way possible, through assemblies and voting.”

Semillero is what they call the kindergarten. Children learn through the orchard behind the large house, where they built wooden games and where they celebrate neighborhood birthdays. Parents do not pay anything to take their children to the semillero, but commit to support working or seeking donations to maintain the dining room and materials for the community garden. They have created a network of merchants and community members who provide food; others show their support by devoting hours to communal space.

In mid-2015, the community garden was closed and state funding discontinued, but participants and townspeople decide to continue with the project oriented toward autonomy, both in terms of content and resources, appealing to solidarity and mutual support.

All of the resources to support the semillero and the cultural house come from food sales on the street, parties and dances, the contributions of fruit and vegetables workers and bakeries. On weekends, they put on an open-air cinema in the Placita de la Autogestión, one of the few communal spaces of the area, recovered by community members and surrounded by colorful murals in which everyday neighborhood scenes are repeated: police chasing teenagers.

The problem of political culture

“The government isn’t in charge of us anymore,” says a voice from the kitchen. A petite old woman, “aunt” Emilia, directs herself to the circle, explaining that the group working the house makes all the decisions, supported by the community members without relying on the state, and “that is called autonomy.” If the public school depends on institutional support, not a single penny gets here. But precarity does not disappear: they work in an occupied house and tap electricity lines.

The commitment of these young people to self-education reminds us of that assertion of an astonished Cornelius Castoriadis, when he recalled that in the nineteenth century the working class “brought itself through a process of self-constitution, taught itself to read and write and educated itself, and gave rise to a type of self-reliant individual which was confident in its own forces and its own judgment; which taught itself as much as it could; which thought for itself; and which never abandoned critical reflection.”[4]

One Sunday in late August, dozens of people from various educational groups in Santiago and Valparaiso met at COPLA. The owners of the house assembled a group dynamic, discussing the problems faced by autonomous, free education in impoverished territories.

Members of La Maleza Collective, a group of recently-graduated high school students from the Maipú commune, decided in 2011 to leave pre-university school to put on the school they dreamed about, with an educational project of its own, appropriated by the community itself. Someone tells the story of how the Community Art School – which has organized a parade, a Víctor Jara carnival, and dozens of training workshops – was born the same year.

Those from La Maleza are dedicated to weaving relationships between the various collectives who have undertaken this journey of self-managed education. They say there are some thirty groups between Santiago and Valparaíso working for education planning to be assumed by the community. In the last ten years, since the “penguin revolution” of 2006, “we have learned that we can’t settle on petitions and demands.”

Real change, they say, will come from that “other education” they call emancipatory, free, communitarian, or anarchist, according to tastes and trends; but what it has in common is that shuns state and market control. They live in a very unstable equilibrium. To be truly autonomous, they would need the miracle of “generating life alternatives in the territory,” or rather in the working-class neighborhoods where people are barely surviving.

When the gaze is lifted and the movement seen as a whole, things change. Historian Gabriel Salazar, one of the most prominent Chilean intellectuals, has a devastating reading of the path that most of the student movement has taken. “It started very well,” he says, “but now has a fundamental flaw: they are not setting out as a social movement of a new type, but as a mass movement of the old type” (eldinamo.cl, September 13, 2016).According to Salazar, true movements deliberate in assemblies, “marches have shown themselves to be useless.” He calls for a grassroots organization that is not limited “to petitioning, to raising party flags, portraits of leaders.” The federation of students, for example, has a president who is elected every year. “[The president] is a big shot, and all the journalists interview him, and then he follows the path of the political class and becomes a little government official.”

This political culture is dead in Chile, where “all surveys show that 98% of the population does not believe in politicians, does not trust them or the system.” Perhaps this is the main fuel of those doing autonomous education: it is almost impossible, but outside, it’s a desert.

Raúl Zibechi, Uruguay, is an international analyst for Brecha of Montevideo, Uruguay, lecturer and researcher on social movements at the Multiversidad Franciscana de América Latina, and adviser to several social groups. He focuses on the South America region and issues of autonomy and grassroots movements. He writes the monthly “Zibechi Report” for the Americas Program.

Resources:

[1] Colectivo Diatriba, “Escuelas Públicas Comunitarias: Propuesta de otra educación para una nueva sociedad”, abril de 2013.

[2] Marcela Fernández Valenzuela, “La experiencia de la Escuela Pública Comunitaria”, ponencia a las XI Jornadas de Sociología, UBA, Buenos Aires, 2015, en http://jornadasdesociologia2015.sociales.uba.ar/wp-content/uploads/ponencias/1228_650.pdf

[3] Se puede consultar el video de 52 minutos hecho por la Escuela Popular de Cine y Patricio Rodríguez de COPLA, en http://escuelapopulardecine.cl/erase-una-vez-en-el-fondo-del-rio-2015/

[4] Cornelius Castoriadis