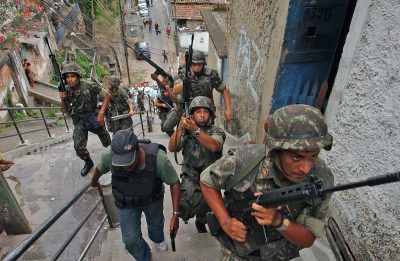

Little has changed in Rio de Janeiro since thousands of army troops were sent to patrol shantytowns and slums considered high risk. The military has been in the streets since the decision by President Michel Temer’s, but it has failed to control the violence and fear that many poor communities in the city experience—and it may even be adding fuel to the fire.

Little has changed in Rio de Janeiro since thousands of army troops were sent to patrol shantytowns and slums considered high risk. The military has been in the streets since the decision by President Michel Temer’s, but it has failed to control the violence and fear that many poor communities in the city experience—and it may even be adding fuel to the fire.

Encounters between traffickers, militias and the military police are a daily occurrence in many neighbourhoods. Data from the app Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire), which aggregates information on shootings based on user-submitted content, points to the astounding number of 16 shootings a day in 2017– 5,817 throughout the year. In 2018, the average increased, reaching 22 shootings per day.

Violence in Rio de Janeiro is not new, nor is the presence of soldiers on the streets. The official pretext of militarizing security to guarantee the security of the population often serves as cover for the interests of a certain class or the government. These hidden interests came to light during the World Cup and the Olympics, when presidents Dilma Rousseff and Temer, respectively, deployed army forces to Rio de Janeiro to ensure security for the event and its participants, without concern for the safety and rights of the local population. While attempting to preserve Brazil’s image abroad, the initial results of the intervention were an increase in human rights violations, burglary and murder among the population the troops were supposed to be protecting.

Violence and Militarization in Rio

Despite an increase last year in shootings, Rio is far from being the most violent state in the country. It ranks about in the middle– tenth out of twenty-seven. That ranking calls into question why it has been targeted for military intervention. Violence is a reality, but would hardly seem to merit such frequent use of the armed forces. In Rio de Janeiro alone, the armed forces acted twelve times since 2008.

The army was also used to patrol the streets during World Youth Day in 2013, Pope Francis’s visit to Rio, and to protect the auction of Libra oil field in 2013 from trade unionists’ protests that the Rousseff government feared could undermine its privatisation process.

The deployment of Armed Forces troops to assume the role of police or collaborate in policing cities and protecting international events is permitted in the Brazilian Constitution. It was initially regulated in 2001 through Decree 3,897 and again by then-Minister of Defence of Dilma Rousseff’s government, Celso Amorim. Amorim signed Decree 3,461 in 2013 to regulate the Law and Order Guarantee (GLO) provision, which allows the military to carry out operations and even assume police duties for a certain period in a restricted area and using limited force.

Favelas such as Rocinha, the Complexo do Alemão and the Complexo da Maré have been the target of military occupation before. In Rocinha, in September 2017, 950 soldiers occupied strategic areas of this favela that is considered the largest in the world for about a week in the midst of a major conflict between drug traffickers. The Alemão complex was occupied in 2010 and the Maré complex for 15 months between 2014 and 2015. According to research carried out among residents of Maré, the military occupation of the favela did not significantly alter the perception of insecurity and fear.

The same study notes that more than 2,000 soldiers were deployed at a cost of almost 600 million reais (or about 200 million dollars) in the Maré operation alone, double what the city government spends on social projects there in six years.

When it comes to the largely black favelas, the government’s emphasis on repression rather than creating opportunities for residents has intensified in recent years, despite the policy’s failure to reduce violence. In July 2017, the Temer administration deployed thousands of soldiers to Rio, citing the GLO. Temer went a step further—not only did he call for the military occupation to take over policing duties in the area, in a blatant intervention in state affairs (yet with full support of the current governor), he removed control over the state’s public security from Rio’s governor, Luiz Fernando Pezão, and effectively passed it over directly to general Walter Souza Braga Netto, who oversees military operations in the eastern part of the country.

The bold federal intervention caused a heated response from some state officials and residents, but it was not unprecedented. Former president Luís Inácio Lula da Silva decreed federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro, exclusively in the area of health, in 2005, though it was not a militarizing measure. His successor, Dilma Rousseff launched military occupations in several Rio de Janeiro favelas.

To complicate matters, the state of Rio de Janeiro currently faces an economic crisis. The state has had difficulty paying its bills (and its employees), with threats to close the state public university (UERJ), and what some experts warn is an imminent collapse in health, education and public safety programs. The state is practically bankrupt.

Rio de Janeiro’s crisis is the result of many factors, ranging from corruption (former governor Sérgio Cabral who governed Rio between 20017 and 2014, was arrested in November 2016, convicted of a series of corruption-related crimes), a lack of long-term planning in key areas, high social inequality, and the aftermath of expenses related to the World Cup and Olympics. The construction of massive sporting facilities and infrastructure drained public coffers and the endemic corruption, high debt and maintenance costs, not to mention the long-term social costs, have left the state struggling to keep its head above water.

The Voz das Comunidades (Voice of the Communities), an important online communication vehicle of the Alemão complex , used Twitter to vehemently oppose the latest military occupation of Rio de Janeiro. “Alemão was occupied for more than a year by military soldiers, then the Units of Pacifying Police (UPP) came and what changed? Nothing! Simply the violence increased, and there were more deaths!”

The portal Faveladarocinha.com followed the same line, denouncing that “in practice, the intervention legitimizes the abuses and violation of rights that are recurrent in the favelas, and gaining more force at this moment”.

Despite such complaints, about 83% of those living in the state of Rio support the intervention, according to research released by the federal government. However, favela residents generally distrust the military presence. During previous occupations, there were complaints of residents being called by racial slurs, destruction of property, and other abuses.

Recent research shows that military actions have dubious results. The costs are high, integrating army intelligence with state intelligence poses obstacles, and in general the biggest accomplishments of the military actions are just the seizure of some weapons and the arrest of some low-level drug traffickers–actions that don’t alter the normal functioning of the arms and drugs trade, or reduce the violence.

Army officials themselves have questioned the recent deployment, saying the army was taken by surprise and that there is no effective planning for specific actions to combat crime or provide guarantees for the military in the field. But the removal of civilian and military police officers involved in corruption, drug trafficking and militias is on the radar of the military command. According to authorities, the Rio de Janeiro police force must be restructured so that when the intervention ends, the state does not return to the previous situation. However, so far nothing concrete appears to have been done.

An internal communication to the troops disclosed by army commander General Eduardo Villas Bôas reported that “the solution will require commitment, synergy and sacrifice on the part of constitutional powers, institutions and, eventually, the population”. His statement increased the apprehension of residents of poor neighbourhoods and experts regarding possible violations of human rights. Troops already operating in the city of Rio de Janeiro since last year tightened the siege in several favelas in early 2018, carrying out searches even of children’s backpacks on their way to school. There are complaints of soldiers taking pictures of anyone leaving their communities to identify them on their return home or to arrest them on site in case there’s a pending warrant. The procedure is illegal under Brazilian law – an officer of the law can check the documents of any person, but they are not allowed to take pictures without explicit consent.

Past military occupations registered numerous abuses committed by the military, such as intrusive searches, threats and offenses, and restrictions on favela residents’ leisure activities as they could no longer party and socialize due to the army’s presence. About 75% of the residents of Maré evaluated the results of the previous occupation as mediocre, bad or terrible. In May 2017, the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro had an effective force of 21,516 policemen. Since July when some 7 to 10,000 soldiers began to collaborate in police work, the increase in boots on the ground has not helped reduce crime and violence.

In fact, one of the most visible outcomes of the military occupation of the state was the brutal murder of Marielle Franco, councilwoman of the small left-wing party PSOL in the city of Rio de Janeiro and a prominent human rights activist. Franco’s death is possibly linked to the action of militiamen that have continued to act freely despite the army presence, which targets criminal gangs linked to drug trafficking.

The question is whether increasing the number of police and soldiers and placing areas under military command solves the problem of violence or merely increases public spending and human rights violations. During the current deployment, the number of police and soldiers will remain the same, but the army is commanding operations.

Virtually immune to prosecution for their crimes, the military this time demanded explicit guarantees that they will have complete freedom of action without fear of legal proceedings or a “truth commission” to investigate possible crimes they commit. Although the demand for virtual impunity so far has not been granted, the armed forces in practice have impunity, since military officers who commit crimes in occupations are prosecuted and sentenced by their peers and not by civilian courts of justice. Civilians accused of defaming military personnel can also be tried in military courts, which have a clear bias, leading to predictable situations in which citizen rights are trampled upon since they face sentencing by a court with a majority of military officers that don’t even have legal training.

Luiz Eduardo Soares, anthropologist and former National Secretary of Public Security, warns that the militarization of Rio de Janeiro could provoke the degradation of civil institutions, similar to what has happened in Mexico, and that the federal intervention only legalizes state brutality.

Iin an interview conducted a few weeks ago with a representative of the Independent Media Centre Maré Vive that covers the Maré favela, who asked to remain anonymous, the journalist stated that the militarization intervention isn’t really focused on reducing crime or to “stop the violence against those who need it the most”, but rather it is a tool to legitimise the same government that brought the city to its current situation.

The Centre’s reports that military actions take place only inside the favelas, but not in the southern and richer portions of the city. They also note that around 80-90% of those living at the Maré are opposed to the intervention “because it is an [military] action that endangers the lives of the residents and in particular puts young people’s lives at risk, on one side and the other. In the favela you only find the retailers– the real drug traffickers are in the South Zone [of Rio], in the congress. The real drug traffickers are the politicians, who are sending the army to the streets.”

The representative of Maré Vive further stated that the army has been in the streets since the 90’s an “It has never worked. Putting more guns on the streets will never work– it does not solve the problem. The slums need social public policy projects: Improve health, education, basic sanitation, transportation; improve public safety in a more responsible way; demilitarise the police, make the police more humane”.

Reports of shootings, houses being invaded, destruction of property and intimidation, and of despair and fear within the population, are commonplace on pages of groups linked to poor communities in Rio de Janeiro. Several NGOs announced they will mobilise to monitor cases of human rights violations and oversee military activity during the intervention, however there are already allegations that the press is being prevented from monitoring operations.

Meanwhile, the violence and illegal activities continue. Favela residents report that once the troops leave, drug traffickers just line up to resume their posts.