On November 21 nationwide demonstrations began that drew hundreds of thousands of Colombians into the streets to protest against the Duque government. Just three years after signing the peace accords, more than 23,000 people have been killed in Colombia. Forty-three percent of the victims are under 25, according to police figures. Forced displacement has forced more than 170,000 people to flee their homes. Following the peace agreement, more than 300 social movement leaders have been murdered, for reasons such as the defense of water and territories in the face of the onslaught of new criminal groups, the defense of water, opposing mining projects, or simply dissenting or defending human rights.

On November 21 nationwide demonstrations began that drew hundreds of thousands of Colombians into the streets to protest against the Duque government. Just three years after signing the peace accords, more than 23,000 people have been killed in Colombia. Forty-three percent of the victims are under 25, according to police figures. Forced displacement has forced more than 170,000 people to flee their homes. Following the peace agreement, more than 300 social movement leaders have been murdered, for reasons such as the defense of water and territories in the face of the onslaught of new criminal groups, the defense of water, opposing mining projects, or simply dissenting or defending human rights.

The sociopolitical violence

The Duque government, through its defense ministers, has been totally ineffective in curbing the wave of selective homicides. Human rights organizations accuse the government of insulting the memory of the victims by minimizing the reasons behind the crimes, attributing them to jealousy, “isolated events” or questioning the leadership style of the victims before they were killed.

The nascent FARC political party, now called the Common Revolutionary Alternative Force, has also denounced systematic homicidal violence against former combatants. The most egregious case was the murder of ex-combatant Dimas Torres by members of the army, which was denounced by the community of Campo Alegre, municipality of Convencion, on the border with Venezuela. In the months following the crime, it became clear that the objective of the attack was the assassination and forced disappearance of the ex-guerrilla by active members of the army.

The nascent FARC political party, now called the Common Revolutionary Alternative Force, has also denounced systematic homicidal violence against former combatants. The most egregious case was the murder of ex-combatant Dimas Torres by members of the army, which was denounced by the community of Campo Alegre, municipality of Convencion, on the border with Venezuela. In the months following the crime, it became clear that the objective of the attack was the assassination and forced disappearance of the ex-guerrilla by active members of the army.

Alongside the acts of violence, videos circulate daily on social networks that film abuses against ordinary citizens by police, abusing their authority in the streets of the cities throughout the country. The videos have caused widespread repudiation of the excessive use of force by members of the police and army.

Alongside the acts of violence, videos circulate daily on social networks that film abuses against ordinary citizens by police, abusing their authority in the streets of the cities throughout the country. The videos have caused widespread repudiation of the excessive use of force by members of the police and army.

Perhaps the straw that broke the camel’s back and contributed to the demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of Colombians, was the bombing ordered by President Duque in August. The attack was announced at the time as a successful strike to prevent the resurgence of the FARC, but it was soon discovered that the victims were 18 children, three of whom were executed by the army. The attack sparked a debate on Political Control in the Congress of the Republic, and forced the Minister of Defense to resign despite the president’s public support for his outgoing minister.

Other causes of the crisis

Months ago, the transnational scandal of the Brazilian firm Odebrecht took a turn in Colombia when the then- Attorney General in charge of criminal investigations was discovered to be involved in a scandal because he was also a lawyer for the wealthiest man in the country, the banker Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo. Luiz Bueno Junior, former president of Odebrecht in Colombia, stated that Sarmiento Angulo was implicated through his Aval Banking group in the alleged reception of bribes for public contracts.

A key witness in the case, Jorge Enrique Pizano, died of a supposed cardiac arrest. Four days later, his son Alejandro died of cyanide poisoning after he drank a bottle of water he found at his father’s desk. Investigations of the case have stalled, but the damage is done and adds to the many corruption cases involving politicians, businessmen, and public officials. The population is getting fed up with evidence of major corruption in a country with a marked economic slowdown since 2016.

Cuts in the public budget and their impact in key areas including public higher education, and the deepening of a neoliberal doctrine that seeks to end the public retirement system, reform the labor system for the benefit of entrepreneurs, and further reduce the basic health system, also spurred the national work stoppage that began on November 21.

Cuts in the public budget and their impact in key areas including public higher education, and the deepening of a neoliberal doctrine that seeks to end the public retirement system, reform the labor system for the benefit of entrepreneurs, and further reduce the basic health system, also spurred the national work stoppage that began on November 21.

Broad citizen disillusionment with the figure of President Iván Duque adds to this complex scenario for the country. Many point to him as being merely a puppet of former president and current senator Álvaro Uribe Vélez, ultra-rightwing politician and leader of the government party “Democratic Center”. As if that were not enough, the Venezuelan crisis has made Colombia the main recipient of a migratory wave that exceeds 1.5 million people, generating outbreaks of xenophobia and social rejection of Venezuelans throughout the country.

The National Strike and the 21N Movement

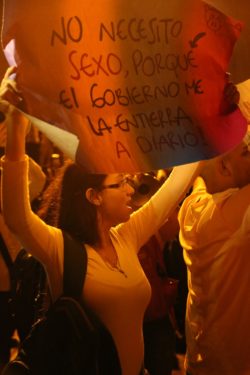

According to official figures, on November 21, 270,000 people marched in Colombia, but that figure is likely much higher because, according to other sources, the official number only takes into account those who took to the streets in the city of Medellín, the second in inhabitants of the country and historically a center of support for the Uribe camp.

The sectors that make up the central committee of the national strike initiated on November 21 find common ground based on opposition to President Duque and his policies, but differ in their demands, which include curbing mining, implementing the peace agreements, protecting the environment, preventing regressive reforms in labor and pensions, fighting corruption effectively, and stopping shark hunting–a move recently approved by the Ministry of Agriculture that generated outrage among environmentalists.

The sectors that make up the central committee of the national strike initiated on November 21 find common ground based on opposition to President Duque and his policies, but differ in their demands, which include curbing mining, implementing the peace agreements, protecting the environment, preventing regressive reforms in labor and pensions, fighting corruption effectively, and stopping shark hunting–a move recently approved by the Ministry of Agriculture that generated outrage among environmentalists.

People of all ages and backgrounds have mobilized in Colombia in recent days, but the role of youth stands out. Many young people have led the demonstrations, and taken on as a crusade the rejection of all kinds of habitual leaderships. They question both Álvaro Uribe on the ultraright and the former left-wing candidate Gustavo Petro for their attempts to use the movement for their electoral ambitions.

On the afternoon of Saturday, November 24, a young man named Dylan Cruz, 18, who finished high school just weeks ago, was seriously injured during a march in the capital city of Bogotá. A police officer from the so-called Mobile Anti-Riot Squadron – ESMAD – fired a tear gas cartridge directly at Dylan that struck him in the head. Almost immediately, social media circulated videos showing the young man running and the policeman shooting him in the back. Dylan died on Tuesday 26 in a hospital, and became a symbol of the movement.

There is also a significant number of young people who have taken to the streets to protest violently. These youth are not in school, have no political affiliations, and don’t have jobs because they lack training. In Bogotá, a group took over a bus, and in Cali they spearheaded skirmishes and direct confrontations with the police.

Youth without opportunites, which in Colombia run in the thousands, are the victims and also the perpetrators of the homicidal violence in the barrios that continue to foment violence as areas of exclusion and marginalization. They feed the ranks of the armed forces, deceived with licit or illicit promises, and they become cannon fodder for grotesque practices like the “false positives” executions by the Colombian Army. These young people do not find in the immediate present many alternatives to build a future.

Youth without opportunites, which in Colombia run in the thousands, are the victims and also the perpetrators of the homicidal violence in the barrios that continue to foment violence as areas of exclusion and marginalization. They feed the ranks of the armed forces, deceived with licit or illicit promises, and they become cannon fodder for grotesque practices like the “false positives” executions by the Colombian Army. These young people do not find in the immediate present many alternatives to build a future.

A Movement Without Owners, but With Many Dreams

In Colombia, it is unlikely any electoral or political force will be able to harvest the massive discontent among the citizenry. On the other hand, the arrogance of a government that disqualifies its opponents as “terrorists” or “vandals”, bodes badly for building the dialogue that the country requires to break cycles of historic violence.

The powerful in the country, understood in all its economic, political, social and academic diversity, now has the historic responsibility to attend to popular clamor that is diverse, complex and full of reasons to make this grassroots protest the beginning of a new stage that can avoid a return to a downward spiral of violence.

After the assassination of the political leader Jorge Eliecer Gaitán in 1948, Colombia entered a period called bluntly “The Violence”. The phrase has been attributed to one of the protesters who said: “Mr Oligarchs: since you did not want to share the country with us, we will raze it to its foundations! Since you did not want to give us a place in our country, there will be no country for anyone!”

Today the need to build a country for everyone is more urgent than ever.

Translation: Laura Carlsen, of Spanish original published here

Photos: Alejandro Alvarez Quijano