The wounds of war have still not healed in El Salvador. Twenty-three years after the peace treaty, victims of the armed conflict are still waiting for justice and looking for their missing loved ones.

Two human rights organizations, the University of Washington Center for Human Rights Works (UWCHR) and the UCA Institute for Human Rights (IDHUCA) presented a request to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for access to documents that prove the existence of a massacre committed during the civil war in the Central American country. The request seeks to help achieve justice in the case.

“We know that there are records of these documents because we had access to them. The minimum that they can do is let us access the documents that have already been declassified. This could help the victims get access to justice,” explained Angelina Snodgrass from UWCHR in a videoconference last October.

According to Snodgrass, the documents are in the hands of the CIA because the US government participated in actions carried out by the armed forces in El Salvador that constituted violations of the human rights of thousands of Salvadorans.

The records of the IDHUCA, which is the entity that began the investigation, indicate that the massacre occurred between February and May of 1981 in the community of Santa Marta, in the departmental capital of Sensuntepeque, 83 kilometers northeast of the Salvadoran capital. A formal complaint before the Salvadoran prosecutor’s office was filed in 2009. The number of people killed is still unknown, but the investigators think it could be around 200.

“We are working to help the victims exercise their rights and we want them to know what happened and who is responsible, so that there will be justice and it won’t happen again,” said Pedro Martínez, lawyer for the IDHUCA.

However, the CIA responded to the petitions saying that for reasons of “national security” it cannot release documents related to military operations in the dates mentioned by the petition.

Furthermore, in a new response to the other petition by UWHCR, the Agency said that it “cannot confirm nor deny the existence” of the documents solicited by the human rights organizations.

___________________________________________________

The CIA said that for reasons of “national security” it cannot release documents related to military

operations in the dates mentioned by the petition.

___________________________________________________

The doors are closing for human rights organizations that are looking for proof of the massacre in El Salvador. The Minister of Defense who was in charge of the armed forces of the country declined to talk about the events and said that no information will be released that is related to military operations that occurred during the armed conflict.

Jaime Campos, an expert in the issue of human rights, explains that El Salvador has refused to cooperate and has hidden information about human rights violations that occurred during the civil war, most of which were committed by the military.

Meanwhile, the Salvadoran prosecution has not ordered appropriate measures to be taken, and has not complied with the requests for exhumations that would allow the investigation to continue and would show how many people died in the military operation. The Americas Program talked to Mauricio Carballo, spokesperson for the institution, who said that the entity cannot share information about the case because it is still under investigation.

And due to the fact that the Amnesty Law in effect in the country—edited and approved by soldiers, politicians and former guerrillas after the peace agreement in 1992—gave “absolute and unconditional pardon to all of the people who participated in political crimes,” access to justice for the victims still seems far away.

The Massacre

The Americas Program had access to the request presented before the court of Seattle, Washington, to which has been added declassified documents about the massacre, which occurred during the armed conflict, and some interviews with military officers who participated in the civil war.

Snodgrass explained that the investigation began with the compilation of documents and publications in newspapers. Later, the organization carried out various interviews with survivors, to determine the places that the victims of the massacre were supposedly buried. Then, they filed petitions for the CIA to release the documents required to continue the investigation.

The principle suspect for having ordered at least two massacres committed by members of the Sensuntepeque detachment is Sigifrido Ochoa Pérez, a retired coronel and former deputy for the right-wing party Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA).

According to documents attached to the demand, the colonel was assigned to the embassy of the United States in Costa Rica. Furthermore, he was assigned to be an adviser for the armed forces of El Salvador during the armed conflict to develop special methods to silence guerrilla fighters, and he was also connected to the murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero in 1980.

According to the documents, Ochoa Pérez ordered the massacres against the orders of his superiors and without consulting then president José Napoleón Duarte, who was in favor of a peace dialogue between his government and the guerrilla fighters.

The Americas Program communicated with the son of Coronel Ocho Pérez to obtain his version of events, but he responded by saying, “the coronel will not make statements about this issue. Thank you.”

“The investigation has brought us to an important issue which is the right to access to public information and justice. Access to justice is a human right, even if 30 years have passed,” said Andreu Oliva, provost of the José Simeón Central American University (UCA).

___________________________________________________

“The investigation has brought us to an important issue which is the right to access to public information and justice.”

___________________________________________________

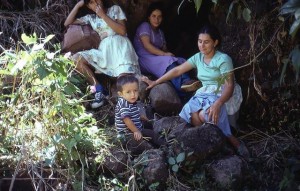

The survivors of the massacre say that during the “scorched earth” operation the military contingent led by Ochoa Pérez came to Santa Marta before dawn. Some people were able to get away but as they ran, they were able to see the bodies of their loved ones and neighbors who had not had the same luck.

During the armed conflict, various rural communities were destroyed by the military, with the objective of preventing more people from joining the guerrillas. The most emblematic case that has not received justice is that of Mozote, where hundreds of people from various municipalities in the department of Morazán were murdered.

There have not been official investigations into the Santa Marta massacre because the people who were able to survive did not report the event out of fear. However, Pedro Martínez of the IDHUCA says that there is sufficient testimony and information that will be completed when the CIA releases the requested documents.

Carmen Rodríguez is a journalist in San Salvador, El Salvador, with five years’ experience in digital journalism. She specializes in the theme of Security and the Law, and joined the Americas Program in 2014.

Photos by Giovanni Palazzo and Philippe Bourgois

Translated by Simon Schatzberg