By Talli Nauman

The anniversary of a fire inside a reactor building at the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant (CNLV) set off the first year of Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo’s presidential term. It was just one of the latest accidents among many at the nuclear facility operated by the Mexican government’s Federal Electricity Commission, CFE. Not until four hours after the conflagration did the alarm sound, evidencing safety and compliance issues. As with other dramatic incidents before it, the public would never have learned of these potentially fatal errors if not for a lone ranger.

In the shadow of Mexico’s only nuclear power plant, physicist Bernardo Salas Mar took it upon himself to alert Sheinbaum to the history of the still-present risks at the plant located near the Port of Veracruz. Salas Mar is waging a one-horse war over the “peaceful atom.”

He and hundreds of others lost their union jobs at Laguna Verde some three decades ago when he exposed corruption linked to environmental dangers emanating from its two reactors.

His revelations made him a golden boy of the anti-nuclear movement. His advocacy gained prominence in the wake of Three Mile Island and Chernobyl meltdowns, long before Fukushima’s reignited international dread over nuclear generation. His peers worldwide accept his juried presentations at competitions abroad.

Yet employers, labor arbiters and human rights officials deny Salas’ claims of job discrimination in his crusade to prevent a radiation disaster at the creaky government-run facility towering over Veracruz state’s Gulf Coast.

Salas complains the domestic energy elite has maintained a chokehold on his role as a professional advisor in an imminent threat scenario.

Having become a pro at using the right-to-know tools that organized civil society developed during his career, he fights on. With his family fending off threats to personal security, he now faces another formidable foe: a newfound global climate policy embracing fission technology.

Environmental experts have shunned this electricity source for its proven deadly history of tragic radiation disasters. But now nuclear industry apologists are convincing international policy makers to tout its perceived role in reducing the greenhouse gas that combustion emits.

They have raised false hopes, because atomic power produces an average 23 times the emissions per unit of electricity generated as on-shore utility scale wind farms, costs five times as much to install and takes five to 17 times longer to put into operation.

Industry tightens grip on policymakers

At the December 2023 U.N. Climate Change Conference, more than 20 nations signed a pledge to triple nuclear energy capacity. Negotiating in Dubai, they declared a nuclear revival is critical for reaching net-zero emissions. Their overdue fix for ever worsening scientific models of survivability was in keeping with the Paris Accord goal of limiting planetary heating. The experimental technology of small modular reactors could help keep global warming from surpassing the pivotal 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit), they wagered.

At the 2024 climate conference celebrated in Baku, Azerbaijan in November, environmental justice advocates rallied with the cry, “Don’t Nuke the Planet.” Yet six more countries signed the pro-nuclear pledge.

The World Nuclear Association, representing the global atomic energy industry, broadcast the September announcement that 14 financial institutions have joined the cause. They are Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank, Ares Management, Bank of America, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Brookfield, Citi, Credit Agricole CIB, Goldman Sachs, Guggenheim Securities LLC, Morgan Stanley, Rothschild & Co., Segra Capital Management, and Societe Generale.

What’s a scientist to do as President?

Enter Mexico’s new President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, a PhD in Energy Engineering, a contributor to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and the former governor of the nation’s smog-plagued megacity capital.

Sheinbaum’s Working Group III excluded nuclear from the industry equation in its 2007 “Mitigation of Climate Change” section of the IPCC’s Nobel Peace Prize winning Assessment Report series.

On Nov. 20, the Nobel Sustainability Trust bestowed her with an Outstanding Contribution to Sustainability Medal during a summit in San Francisco. The Nobel Family called her out for having “championed sustainability through policies aimed at reducing carbon […] while also encouraging community involvement in environmental decision-making.”

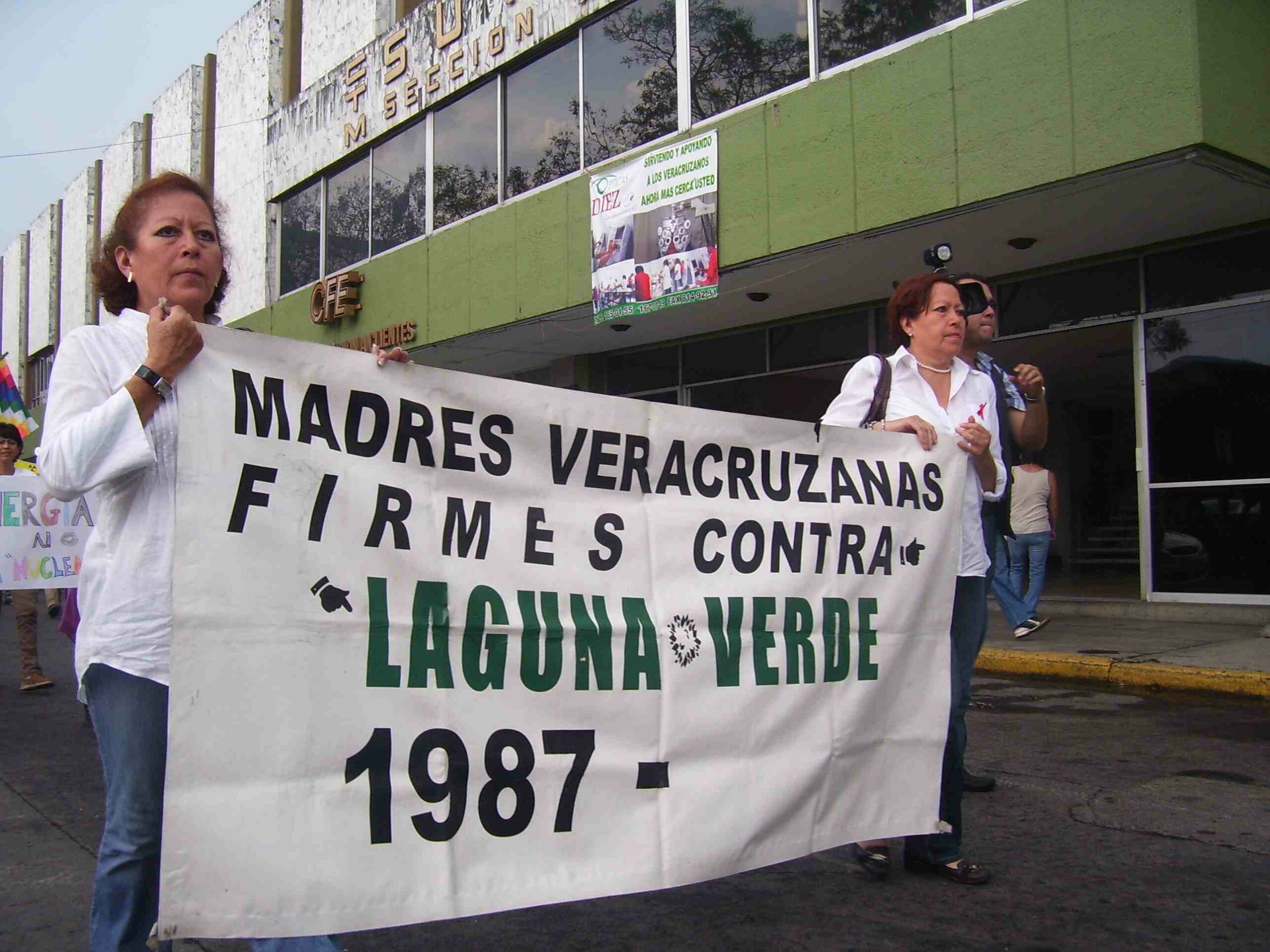

As Mexico’s first female chief of state, she stepped into to the National Palace on Oct. 1 with debts owed the women’s movement: among them, the legacy of the Veracruz Antinuclear Mothers (Grupo Antinuclear de Madres Veracruzanas) who picketed steadfastly every Saturday during more than eight years for a safety audit of Laguna Verde.

No sooner had Sheinbaum won the election to office on June 2, than Salas solicited an audience with her to counter a recommendation she inherited for building another reactor during her six-year term.

So far, she has been receptive to his July 15 argument. Most criticisms of her energy project — also inherited — focus elsewhere. They derive from private investors aiming to garner a bigger piece of the public infrastructure pie.

Cards are stacked

Mexico, under Sheinbaum, has not caved to the global pro-nuke caucus. Yet a look at the books reveals a stealthy rise in federal support for not only boosting Laguna Verde but also the domestic spread of small modular reactors already programmed.

The 2024-2038 National Electric System Program calls for buildout of 2,350 MW of nuclear capacity. That would more than double the maximum installed 1,620 MW that manufacturer General Electric provided. The prescription relies on the “expectation that in the medium term, integration of technology for lower capacity nuclear power plants will become accessible.” One megawatt of power can light approximately 1,000 homes.

Salas has cautioned every one of the previous four presidents Laguna Verde. At the end of the past administration, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO, dismissed Salas’ concerns and endorsed the project of a third reactor. To a reporter ‘s express question July 8, “¿Habrá un tercer reactor en Laguna verde?” AMLO said, “The specialists consider it viable. That proposal has been made here”. However, he left the decision to his successor, saying “She is an expert and she has to analyze it”.

AMLO statement flicks off safety switch

The statement flicked off a safety switch, unleashing pent-up yearnings of the pro-nuclear establishment.

AMLO’s Energy Minister Rocío Nahle, who took office as governor of Veracruz on Dec.1, lamented plans left on the drawing board for a third reactor during his tenure. She said Laguna Verde “represents clean, constant, cheap energy.” Touching nerves already frayed over the prospect, she said, “I am pro-nuclear, but I expect that Claudia, who also knows a lot about the subject, can analyze it.”

Within the month, Salas’ electricians trade union Sindicato Único de Trabajadores Electricistas de la República Mexicana (SUTERM) fully backed plant expansion.

The former president of the Mexican Nuclear Society, Gabriel Calleros Micheland, a member of the Academy of Engineering, supported the proposal for the federal government to build a third nuclear reactor at Laguna Verde. He spoke out during a media conference in the company of similarly aligned representatives from other organizations.

Physicist counters industry hype

Salas submitted a letter to Sheinbaum “to present certain considerations that I hope will help you decide whether or not to install a third reactor at the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant (CNLV) or at any other site in the Mexican Republic.

As a mathematical physicist, he stated: “I am in favor of nuclear energy for peaceful uses. Unfortunately, the two nuclear reactors at Laguna Verde have not been a good option, although the authorities, through deception and concealment of information, want to make people believe otherwise.”

He followed up with a copy to the news media of his hand-delivered request. He tacked on an International Atomic Energy Agency inspection report that showed 14 shortfalls in “Safety Aspects of Long Term Operation” at the seaside power plant. Despite the assessment, before completion of agency prescribed measures, federal regulators authorized the creaky installations to keep performing through 2055 – 30 years after their expiration dates.

Only 10 days into her term, Sheinbaum, at the daily presidential media conference, reassured constituents, “I am not very pro-nuclear.” She said, “Nuclear power generation does not produce greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, but it has its risks”.

How the nuclear chain pollutes

To be clear, the boiling water that creates the steam powering Laguna Verde’s turbines results from the splitting of atoms to release heat. That in itself does not churn out emissions. However, nuclear energy relies on a chain of CO2 pollution processes. The links are in the form of mining the uranium, mineral refining, transportation of the fuel source, construction of the plant, gas-powered backup generation to assure constant transmission, and thermal combustion to destroy waste, as well as energy expenditures for long-term confinement of radioactive residuals.

As to “its risks”: Uranium miners and residents downwind or downstream from mines have higher incidence of cancer related to radioactive particles and radon gas. Consumed nuclear fuel rods are radioactive waste, stored at the reactor site. The government must maintain and fund their isolation for at least 200,000 years – far beyond the lifetime of the power plant. The more nuclear waste that accumulates, the greater the risk of radioactive leaks, which can damage water supply, crops, animals, as well as humans.

In addition, it promotes the threat and cost associated with weapons proliferation, as well as meltdowns – something which clean, renewable energy production avoids.

Due to these “other environmental impacts,” Sheinbaum said, “at the moment, we have no plans to grow with nuclear power.”

Federal budget limitations, best defense against nuclear plant expansion

In an Oct. 14 media release, Salas congratulated Sheinbaum “for her wise decision to cancel the construction of the third nuclear reactor at the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant, because the two current reactors are poorly operated and constitute a risk to the population’s health.” He told the Mexican Environmental Journalists Network he would keep informing the President “of any irregularities that continue to occur.”

However, Sheinbaum did not promise to cancel anything. She merely dished out a diplomatic answer to the media. Naturally, if the minimum time for building and activating a reactor is five years, Mexico most certainly will not “grow with” nuclear during her six years in office. The most it could do is spend down the federal budget for an unpopular project – quite the opposite.

Salas, in his letter to Sheinbaum, mentioned, “You should know that, unlike other electricity generating plants, such as hydroelectric, thermoelectric, geothermal, etc., the CNLV has not been inaugurated by any Mexican president, due to the unpopularity of nuclear energy and the serious accidents that have occurred worldwide”.

Salas went on to ask Sheinbaum to review his termination from the workforce at the power plant. He blamed it on his report to his union SUTERM about “the corruption in contracts and acquisitions by high-ranking authorities.” He noted, “I also pointed out the failure to comply with international commitments in nuclear and radiological matters, because as a Mexican I think it was my obligation.”

Seeking Revindication

Initially, he said, he received no support from his supervisors or his union for the proposals he made to solve the problems. He lodged complaints within the framework of the plant’s total quality management program, but to no avail, he said.

In April of 1996, he appealed to the union, the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic (Procuraduría General de la República), the Secretariat of Comptrollership and Administrative Development (Secretaría de Contraloría y Desarrollo Administrativo), the Federal Board of Conciliation and Arbitration (Junta Federal de Conciliación y Arbitraje), the National Nuclear Safety and Safeguards Commission (Comisión Nacional de Seguridad Nuclear y Salvaguardias), the Federal Electricity Commission, the Human Rights Commission of the State of Veracruz (Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Estado de Veracruz), and the International Labor Organization.

Salas denounced “irregularities, […] abuse of power” and “the haste with which decisions are made that put at risk the safety, not only of the workers, but of our plant.”

The legal claims he leveled substantiated dozens of spurious transactions with disregard for radiation counters’ intended purpose of worker health and safety. The assertions included discrimination against women in the labor pool.

Refuting the charges on behalf of the Federal Electricity Commission, plant Manager Rafael Fernández de la Garza said “Salas is totally wrong. We terminated him for being lazy. He is pouring out his bitterness, attacking us.”

The CFE fired Salas a month later. “The reasons for the termination are that you committed a lack of integrity or honesty,” explains a copy of a letter addressed to Salas and attached to a document denying all his accusations against management.”

But the Veracruz Mothers’ Anti-Nuclear Group took advantage of his expertise to bolster their demands for an investigation. They published a notice asking: “What more evidence is needed to suspend work and audit the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant […] after the complaint filed by the physicist Salas Mar?”

Alejandro Calvillo, then coordinator of the energy program at Greenpeace Mexico, reacted, “Bernardo’s case confirmed many of the things that the anti-nuclear movement maintained.” The international organization had already supported the Veracruz mothers’ demands by leading a demonstration with its boat Moby Dick in front of Laguna Verde.

After his discharge from 13 years working among the 1,000 employees at the plant, Salas obtained an academic post at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Since 2000, he has kept watch over Laguna Verde from his position as director at the Workshop on Radiological Analysis of Environmental Samples in the Science Faculty’s Radiology Laboratory.

He revealed cases at home and abroad

Among other things, Salas reported the use of a clandestine radioactive waste incinerator. He presented evidence of Fernandez de la Garza’s $1-billion fraud in bid letting on turbine replacement. The Federal Ministry of Public Administration put the plant manager on unpaid leave in 2006. Fernandez unsuccessfully sued Salas for defamation.

The International Atomic Energy Agency published Salas’ 2013 findings of fissures in both reactor towers’ ocean water jet pumps. He credited employees with letting him know when the reactors simultaneously shut down in 2012. Veracruz residents feared a radiation event, as management and regulatory authorities kept mum.

He also credited the Federal Institute for Access to Information (IFAI, then INAI) with helping him garner the answers explaining the episode and said the public had not been endangered. However, in his exposé to the IX Latin American International Radiation Protection Association’s Regional Congress in Rio de Janeiro he recommended taking both reactors out of operation until the pumps could be replaced.

In 2014, Salas sent a letter to the Chamber of Deputies, saying 86,000 tons of radioactive waste had accumulated at the plant. Since it was warehoused in temporary facilities long past the deadline for removal, it can escape into the environment, he wrote. “The nuclear energy generated by Laguna Verde is not clean energy.”

He reminded them of a historic fire at the Dry Solid Radioactive Waste Depository. He mentioned the area’s frequent hurricanes, such as Roxanne, which produced winds that ripped the tin roof off a warehouse in 1995.

A report Salas later obtained from regulators at National Commission of Nuclear Safety and Safeguards (NCNSS), cited failure to conduct the required stabilization of the hazardous material for 15 years from that date. “It is not possible to try to build more reactors without first solving this problem of radioactive waste,” he argued.

Horror stories

Also in 2014, Salas revealed to the International Symposium on Solid State Dosimetry the loss of the custody chain on a neutron emitter and a particle accelerator. The radiological instruments, necessary to create nuclear reactions, disappeared when the university abruptly closed down his laboratory in 2011. The devices showed up later, but the International Atomic Energy Agency published the study in the interest of fomenting best practice in nuclear safety culture.

His freedom-of-information requests turned up evidence of falsified certification exam procedures and results in job promotions during 2015. This led him to speculate in the media as to how long such duplicity has persisted.

Some of Salas’ 150 informants inside Laguna Verde, who count on him to put out the word for their safety, helped him document a dangerous unauthorized operation in a reactor in August 2020. Conducting work without the required protective emergency shutoff panels raised the threat status there from yellow to orange, he said. Similarly, orange alerts occurred every following month through January 2021.

Additionally, in both November and January, personnel had to effectuate reactor SCRAMs, or emergency shutdowns of fission activity. A risk evaluation Salas procured and delivered to AMLO determined “a large radioactive discharge into the environment” with a “probability of a severe accident.”

A single such incident could contaminate most of the country and part of Texas, Salas warned. Ionizing radiation released would kill living cells, cause mutations, alter DNA, lead to cancer and result in fatalities of humans, as well as all other living things.

Yet, neither he nor the Veracruz Mothers’ Anti-Nuclear Group, have ever been able to pressure plant management to carry out the requisite industry-standard simulated emergency evacuation exercises – even within the 16-kilometer radius of the estimated accidental radioactive plume pathway, as Argentina, for example, has done 42 times.

He went on to sample the levels of ambient radioactive elements and those that may be from Laguna Verde along the entire Gulf Coast of Mexico. During the three-year, season-round study, his team found radioactive products of fission in the plant vicinity. Oxford University Press published the results. The activity laid the groundwork for an envisioned “Radiological Characterization of the Mexican Republic.”

One year after Salas’ alert to the Chamber of Deputies, federal regulators sanctioned Laguna Verde’s Radioactive Waste Department for acting “in an irresponsible, indifferent and careless manner.” He found out by filing a freedom-of-information inquiry.

He made a citizen complaint to the Environment Ministry in 2017, when it authorized construction of a nuclear waste storage facility without the required environmental impact study. He filed another with the National Human Rights Commission over the plan to have Mexican Navy recruits guarding the construction at the risk of their health.

By the end of 2021, the most recent available documentation of any solution to the problem was a cancellation of bid letting for a waste incinerator.

He documented the inadequacy of emergency evacuation routes around Laguna Verde, before and after 2019 Tropical Storm Barry, in an effort to prevent a coastal real estate development perilous for residents and in contradiction to safety guidelines.

In 2023, Salas informed peers in Seville at the ENVIRA 2023 – 7th International Conference on Environmental Radioactivity of spent fuel rod storage outside Laguna Verde’s security monitored perimeter. Among other carcinogens, it contains Plutonium-239, the raw material for atomic bomb building, of interest to international organizations concerned about nuclear weapons proliferation, he said. “It is outdoors and outside the secured double fence around the reactor buildings. So, it could be considered at the mercy of terrorists,” he noted.

In 2024, Salas revealed to the world that a number of Laguna Verde employees suffered radiation overdoses during reactor refueling and other activities. Through freedom-of-information requests, he obtained documentation that federal inspectors discovered plant management covered up the overdose information. The paper trail revealed the enforcement agency failed to suspend the reactor operating license for that breach of regulations.

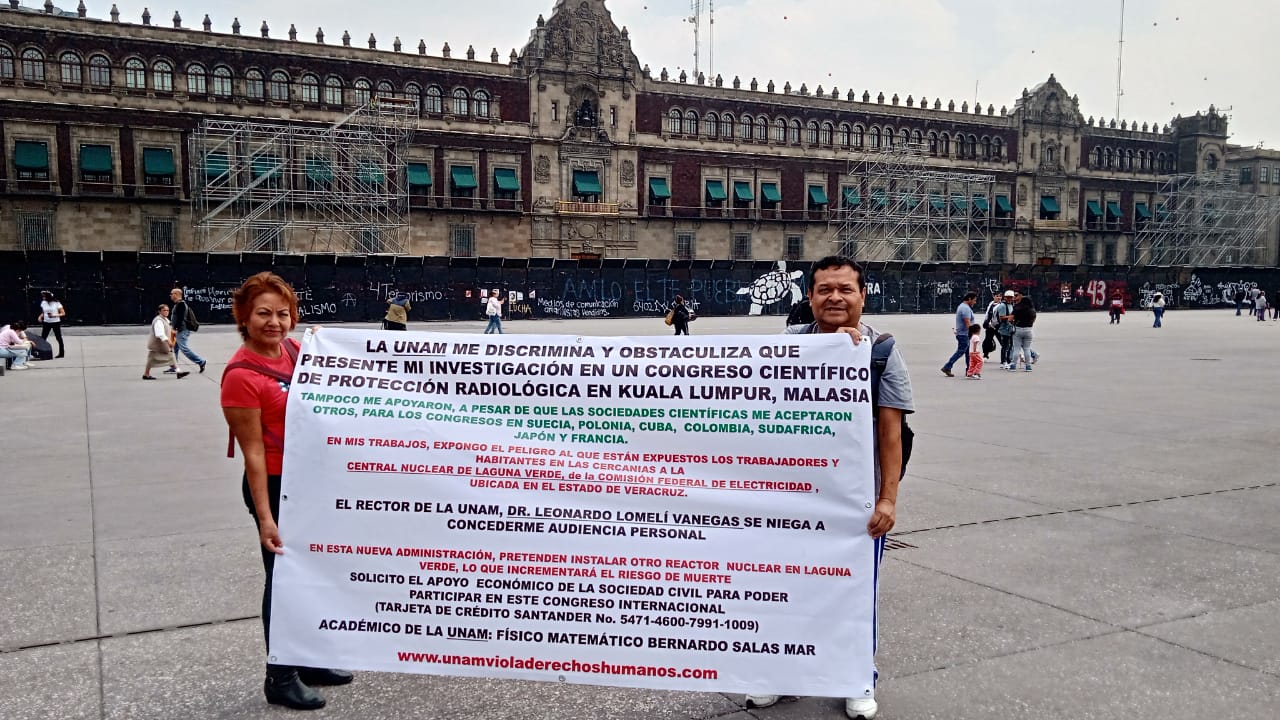

The 11th International Conference on High Level Environmental Radiation Areas invited him to Malaysia to present the findings Oct. 28-29. However, his university administration would not permit him to represent them, much less underwrite the trip expenses.

Waning support

Salas had the full support of his employers and faculty for six years, he said: “Initially, when the UNAM gave me permission and supported me in presenting my research, I was able to present it at international conferences organized by the International Radiation Protection Association (IRPA) in Huelva, Spain; Lima, Peru; Austin, Texas (USA); Acapulco, Mexico, etc.”

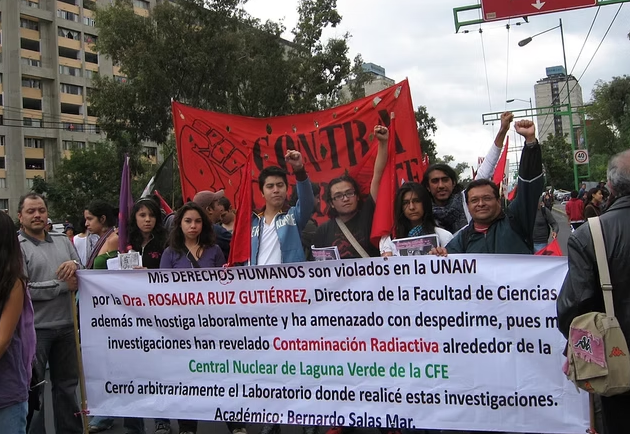

But during the most recent nine years, he experienced mounting labor discrimination and harassment, he told MIRA. He sought to defend his watchdog position by filing a case at the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH).

After 50 appeals to the CNDH with no satisfaction, he went to the federal court. It ruled in favor of the Commission’s 2009 declaration that the case did not demonstrate abuse by authorities. So he filed the case at the UN’s Inter-American Human Rights Commission. In so doing, he stated:

“I must point out that the discriminatory treatment and workplace harassment committed against me at UNAM, does not apparently have its origins in this university, but is due to my activism in favor of the environment and vulnerable groups allegedly affected by the radioactive contamination emitted by the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant and for expressing my concern about the irresponsible way in which said nuclear power plant is operated.’’

This writer’s attempt to obtain the lost file at the Commission’s tribunals failed to elicit a response from the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, which had offered a funding opportunity for investigation of the case at the U.N. agency.

Hostile conditions

Rosaura Ruiz Gutiérrez, Sheinbaum’s former Secretary of Education, Science, Technology and Innovation of Mexico City, had turned on him while acting as UNAM Science Faculty director. Written testimony from a university appeals board member indicates she said she wanted to fire him and would penalize him if he traveled to Brazil on the invitation to present his radiological findings.

She locked him out of the workplace, produced no chain of custody report on the radiological instruments left unattended there, and then blamed him for stealing them, his plea to the Inter-American Human Rights Commission states.

She denied Greenpeace requests for him to test journalists for radiation doses received while reporting the Fukushima meltdown and to survey radiation sources in Hermosillo, Sonora, in the wake of a cluster of cancer deaths. Then she canceled his employer’s health benefits package, the complaint adds.

He won a ruling at the Federal Conciliation and Arbitration Board for reinstatement of his job and the bonus pay in 2018. Nonetheless, when the university appealed, his defense lawyer at the government’s Federal Labor Defense Attorney’s Office (Procuraduría Federal de la Defensa del Trabajo-PROFEDET) tried to obviate the achievement. PROFEDET’s public defender argued for his firing in order to access 25% of his unemployment benefits, Salas said.

While Salas was seeking a different lawyer, Sheinbaum carved out a new ministry for Ruiz to run the Secretariat of Education, Science, Technology and Innovation (Secretaría de Educación, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación-SECTEI). From her Cabinet chair, Ruiz can compel the cancellation she procured of his performance bonus. She’s “attempting to subjugate me by trying to starve my family, which is why she is cancelling 40% of my income from the Performance Bonus Program for Full-Time Academic Staff,” Salas said.

Ruiz’ successor, Science Faculty Director Víctor Manuel Velázquez Aguilar, denied his request for travel expenses to Malaysia, so he took to the Mexico City streets in hopes of raising awareness of his predicament and funds to attend the conference. He failed to collect the money in time for the trip to join peers in Southeast Asia. However, he did land a long-sought meeting with the Faculty director about these issues.

Unfortunately, Salas informed the Mexican Environmental Journalists Network, the meeting failed to produce the desired results. Velázquez insisted, “UNAM is not interested in the effects that Laguna Verde has on the health of the population and the environment; he reiterated that I should not conduct environmental studies on Laguna Verde, nor present such work at international conferences,” Salas divulged.

This publication asked Velazquez, in writing, to corroborate. UNAM’s Coordinator of Management of the Secretariat for Prevention and Support for University Mobility and Security confirmed receipt of the correspondence. However, Velazquez dismissed the inquiry.

“I believe that my days are numbered at UNAM, so I will persevere, practically alone, in my trench and I will inform you of what happens,” Salas said.

What can you do?

Instead of conferring with colleagues in Kuala Lumpur, Salas ended up staying home eyeing media reports of tropical storm inundation engulfing traffic on Laguna Verde escape routes.

His parting words in his human rights complaint constitute Mexico’s best shot at pushback against proliferation of nuclear power plants and their perpetual menace.

“The first way to contribute to this cause is by spreading this message among your contacts to ensure that this problem is widely known by society,” he said. The priority is “achieving that the UNAM authorities change their attitude and become part of the solution and stop being part of the problem, as they have been to date.”

More details on how to help: here.