On February 28, just over 50% of the Salvadoran electorate went to the polls to vote in mid-term elections. This ended up giving more power to incumbent president, Nayib Bukele, by increasing his party’s qualified majority in the Legislative Assembly.

Preliminary results indicate that his New Ideas party (Nuevas Ideas, NI) will have 56 seats in the legislature, enough to eliminate any need for alliances to approve Bukele’s initiatives, as well as to seat justices on the Supreme Court and the Court of Accounts, and to confirm an Attorney General and Attorney for Human Rights.

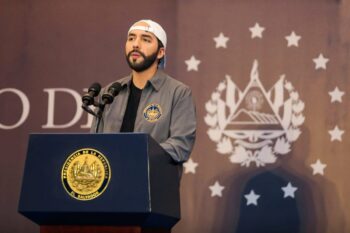

Bukele, the youngest president in Salvadoran history, has been harshly criticized in his less than two years in office, including accusations of violating human rights, the free press, and democracy itself. For example, on January 9, 2020, the Legislative Assembly was taken over by the military to pressure deputies into approving a large loan. He has also been accused by journalists, activists and human rights defenders of promoting attacks on free expression.

At the same time, Bukele is facing a suit before the Central American Court of Justice for allegedly violating the constitutional rule of law. The complaint was filed by Napoleón Campos, a Salvadoran lawyer and former diplomat, who charged that the president “has gradually and progressively placed the democracy of El Salvador in a vulnerable and dangerous position.”

Even since before assuming the presidency, Bukele has responded to criticism using rhetoric that has taken the country to its highest level of polarization in recent years. And now his NI party has achieved what no party has ever achieved in a single election—a qualified majority in the legislature.

“The voters have opted for an authoritarian and autocratic profile, giving (to Bukele) almost absolute power,” said Celia Medrano, a journalist, human rights activist, and candidate for executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). “The next government branch to fall will be the judiciary, which was already operating with caution and fear in the face of the executive branch, even before it took control of the Legislative Assembly. With some exceptions, both the Public Ministry and the Judicial Organ will maintain an even more timid and permissive profile than they have up to now, expecting the official party to appoint second-rate functionaries who are loyal to the president.”

According to Professor Alfredo Cantarero of the Francisco Gavidia University, the February 28 legislative and municipal elections results can be attributed to a desire to punish both the left-wing and right-wing parties who alienated their constituents as they alternated in power over the last 30 years. Another factor, he said, was support for Bukele’s media-driven promise to get rid of “the same ones as always.”

“In every moment of the four ARENA administrations and the two of the FMLN, people pinned their hopes on being recognized and favored by both parties,” Professor Cantarero told university radio. “But the bulk of the government functionaries’ actions favored only their own pockets and the pockets of those they represent. The citizens were merely an excuse for taking advantage of the power granted electorally.”

The concerns of human rights defenders and NGOs are rooted in the fact that Bukele has long demonstrated authoritarian traits and that his speech has focused on the weakening of government institutions in order to avoid accountability and transparency. These citizen activists warn that little by little, the state institutions already controlled by the president will silence all criticism, opposition, questioning and inspection.

As Medrano put it, “With the already weak democratic institutions trampled by populist practices, you cannot expect anything else but the voiding of any manifestation of criticism or opposition. Coercion and pressure await those who take critical positions. They’ll be the first to suffer the effects of the consolidation of a state structure aligned with a single power and without counterweights.”

The legislators that Bukele can now count on have indicated that they might consider a constitutional reform allowing for presidential re-election. With the next Legislative Assembly taking power on May 1, 79 votes from Bukele’s allies would be enough to pass such a reform. In fact, the government named a special commission last November, headed by Vice President Félix Ulloa, charged with investigating the matter.

“When the euphoria wears off, February 28, 2021, will be remembered as the day in which “democracy” killed Democracy in El Salvador,” Medrano told The Americas Program. “By democratic means, a group prone to authoritarian power, plagued by old practices and old actors, managed to put in place a fresh image for El Salvador.”

Rejected in Washington, D.C.

In the first year of Bukele’s term of office, during which the military takeover of the Legislative Assembly took place, the U.S. posture toward El Salvador was indifferent. The harsh criticism and accusations of violations of the rule of law, human rights and freedom of the press were ignored by U.S. President Donald Trump.

In fact Trump and Bukele have a lot in common: Nayib seems to have followed Trump’s script to the letter. After all, both promoted an insurrection in the congressional building that fell short of consummation. When Bukele sent the military into the Assembly, he asked his base to be ready and if necessary to remove lawmakers from the site.

Like Trump, Bukele promotes attacks on the media and discredits the independent, non-official press. The current number of formal complaints of attacks on journalists and media organizations hasn’t been seen since the war. This is in addition to the other criticisms and accusations he faces for disrespecting El Salvador’s laws and institutions. And in another Trumpian echo, Bukele’s family works in the Cabinet, hiding public information and spreading theories of electoral fraud.

Says Medrano, “We can see points in common between the former U.S. president, Donald Trump, and the current Salvadoran president in at least five areas. The use of social media to transmit messages of hate. Using hate as an instrument of electoral campaigning. Denial of history. A refusal to accept the reasons that laws are designed as they are. Ignorantly mocking or attacking other state organisms.”

Just days before the elections, the hate that Bukele has aroused since he assumed the presidency provoked an armed attack against members of the left-wing party perpetrated by two members of the private escort of bodyguards of one of his ministers. And like Trump, who seldom condemned xenophobic crimes motivated by racism, Bukele failed to condemn the murder of two FMLN militants, Gloria Rogel de López and Juan de Dios Portillo Tejada, both older adults who were taken down on a public street last January 31.

The Salvadoran president, again taking a page from Trump’s playbook, justified the crime by claiming that it had been carried out by the leftist party itself. However, three of the health minister’s bodyguards were arrested, and according to prosecutors ballistic tests showed that one of them was the murder of the FMLN militants.

A week after the event, on Thursday, February 4, word spread among the Salvadoran community in the U.S. capital that Bukele was in the city. Former Salvadoran diplomats corps, members of the Salvadoran diaspora and some journalists tried that night to confirm the rumor. An unannounced and unofficial visit to the U.S. capital raised questions.

The next day, Friday, February 5, it became known that Bukele had met that morning with Luis Almagro, the secretary general of the Organization of American States (OAS). Almagro himself has faced questions about why he has not addressed the ongoing accusations of human rights violations against Bukele, or of his dictatorial conduct relating to the Covid-19 pandemic, such as detaining for weeks hundreds of people arriving in El Salvador on the pretext that they needed to be kept under observation and allowing police officers and soldiers to use force in arresting any of them who did not follow their instructions.

Almagro, who has betrayed a clear right-wing bias as head of the OAS, had also failed to comment on the military incursion into the Legislative Assembly, orchestrated by Bukele. He did, however, designate an observer mission to oversee the Salvadoran elections, days after Bukele denounced, without evidence, a supposed coup plot against him and warned, months in advance, of planned electoral fraud.

On Monday, February 8, the Associated Press confirmed Bukele’s Washington visit. It also reported that functionaries in the Biden Administration refused to meet with him. In an interview on El Salvador’s Canal 33, Dan Restrepo, a former adviser to President Barack Obama, confirmed Bukele’s presence in Washington and the refusal by federal officials to receive him.

“It’s well established here in Washington that he sought meetings and that he never got even one,” Restrepo said in a video call. “I know that first-hand.”

The former adviser noted that the message sent by the Biden Administration to President Bukele was clear. “It’s quite obvious … that those who respect democratic frameworks, the rule of law, will be close partners with the United States and those who go outside those frameworks will have a more complex relationship,” said Restrepo.

Although there is no official information — and Bukele denies it — the talk in Washington is that two agencies that Bukele sought meetings with are the State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs and the National Security Council’s equivalent office. The latter is headed up by Juan González, one of President Biden´s top policy hands for Latin America..

The Meeting With Almagro

Bukele’s visit to Washington, in which Luis Almagro, the OAS secretary-general, was the only official that received him, was also confirmed to the AP on February 8 by Alejandra Hill. Without offering details, the Salvadoran foreign minister said the trip was “short and private”. However, Bukele, amid criticism and ridicule, initially denied that any such trip took place. Later, he denied having requested meetings with Biden Administration officials. Finally, he lashed out at the media that reported on his failed visit.

“We cannot trust the international media,” he told members of the Salvadoran diplomatic corps whom he had assembled to rebuke the reports about his trip. “For example, the AP said that I had gone to the United States to ask for a meeting with President Biden and they refused me. That is a lie . . . With all the disinformation that exists at the worldwide level I think it is important that you report this type of information.¨

The Americas Program obtained the official register from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that confirms Bukele’s entered Washington on February 3 and departed from there on February 5. Bukele has never acknowledged the trip, despite Hill’s statement that it was “short and private.”

Although the press office of the OAS said that it had “no information about it,” sources close to the organization confirmed to The Americas Program and La Prensa Gráfica that the Salvadoran president was with Secretary-General Almagro that Friday.

Almagro had stayed silent when the Trump Administration implemented anti-immigrant policies. Bukele, for his part, readily embraced those policies. Despite El Salvador’s lack of security capability to protect its own citizens, he signed onto Trump’s “safe third country” agreement that allowed the United States to send rejected immigrants to Central America.

According to the sources that confirmed the Bukele-Almagro meeting, who requested anonymity, the Salvadoran president asked the secretary-general for help in regard to the February 28 congressional and mayoral elections.

The same sources close to the OAS said that Bukele directly stated to Almagro his government’s refusal to back the candidacy of Celia Medrano for executive secretary of the IACHR.

Even though the task of filling that post falls to an OAS council without the participation of the secretary-general, each candidate needs to obtain the backing of her or his government in order to score points and be chosen. Instead of supporting Medrano, Bukele has dedicated various tweets to discrediting her and calling into question her long career as a journalist and human rights activist, no doubt owing to her complaints about the corruption and impunity attributed to his government.

Medrano has also pointed out that Bukele shares with Trump “governing methods of an authoritarian and populist character” and that by comparing the two administrations it is possible “to understand what is happening and the risk of there being permissiveness and tolerance” on the part of the international community. This posture of hers does not sit well with the Salvadoran president.

In response to the possible negative influence on her candidacy from comments about her that Bukele may have expressed, Medrano said she expects that the selection process to be carried out properly and that the naming of the next executive secretary will be based on “suitability” and the candidate’s profile, not on outside objections.

“I do know that that atmosphere of the Organization of American States is such that an objection lodged by a head of state can have veto power,” she told The Americas Program. “Still, I can only suggest that the decision be based on an analysis of merit and suitability. Whatever the results are, however, I won’t abandon the work in defense of human rights that I have been carrying out.”

It turns out that Bukele paid $780,00 to a Washington lobbyist firm late last year to clean up his image, which had been stained by ongoing criticism and accusations of human rights violations and of threats against El Salvador’s democracy.

Coincidentally, after his meeting with Bukele in Washington, and while Salvadoran administration officials and candidates of Bukele’s New Ideas party were spreading conspiracy theories of alleged electoral fraud in the making, Almagro sent a special OAS mission to assess the political tension in the country.

“The secretary-general of the OAS accepts the Republic of El Salvador’s request to send a special mission in order to evaluate the institutional political situation and contribute to the preservation and strengthening of the rule of law,” reads an official communication to El Salvador.

That appointed body dismissed the election fraud theory promoted by Bukele and his allies, but in the days following the vote it highlighted that the legislative elections took place in a highly polarized atmosphere in which laws were disrespected.

A Change in U.S. Policy

Since September of 2020, a number of U.S. senators and congressmembers, both Democratic and Republican, have voiced concern about the “growing hostility” promoted and carried out by the Salvadoran government and by Bukele himself, and have sent four letters to the Salvadoran president expressing that concern.

After Joe Biden’s victory in November, there was talk about a radical change in the U.S. posture toward the Bukele government. This shift, said Restrepo, a former Obama adviser, explains the refusal from the Biden Administration officials to receive the Salvadoran president.

Mari Carmen Aponte, who served as the U.S. ambassador to El Salvador under Obama from 2012 to 2016, warned that the passive stance that the White House maintained under Trump will change and that the Biden Administration will be sending messages not just to the Salvadoran government but to all governments that threaten democracy.

“Nayib Bukele should be aware that that there can be a change in the United States and that the Biden Administration will not be so passive,” Aponte told Canal 33. “Governments will receive some strong messages addressing corruption and situations that corrode democracy.¨

After the military incursion into the Legislative Assembly, “alarms sounded” in Washington. Various Democrats in the House of Representatives, including Norma Torres, Jim McGovern and George Meeks, were the first on that body to point out that El Salvador is facing a weakening of its democracy.

Congresswoman Torres added that the “conditions” Bukele has created in El Salvador make cooperation difficult, given that there are no guarantees that the government will fight against corruption.

Combatting corruption in the Northern Triangle region of Central America is one of the pillars of the foreign policy that Biden is establishing for Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The aim is to reduce the causes of Central American migration.

Carmen Rodríguez is a journalist in San Salvador specializing in issues of security, justice, migration and international relations. She has been a contributor to The Americas Program since 2014.