Rio de Janeiro. While smoking his tobacco pipe in front of his small cinder block home toward the top of his native Vidigal, a sprawling favela overlooking some of Rio de Janeiro’s most luxurious neighborhoods, Jamil Jorge offered his thoughts on Brazil hosting the World Cup in the midst of the tournament: “The World Cup only benefits people and institutions with money, not people like me.”

Rio de Janeiro. While smoking his tobacco pipe in front of his small cinder block home toward the top of his native Vidigal, a sprawling favela overlooking some of Rio de Janeiro’s most luxurious neighborhoods, Jamil Jorge offered his thoughts on Brazil hosting the World Cup in the midst of the tournament: “The World Cup only benefits people and institutions with money, not people like me.”

Jamil had just finished meditating during a breezy ocean-side night at one of the many stunning lookouts that Vidigal offers. The public viewpoint lies at the foot of one of the many homes of none other than David Beckham–reflective of the uneven and volatile development Brazil has undergone over the last decade alone. Recent years have brought tens of millions into the middle class but left plenty of others behind, as suggested by a low 85th ranking in the United Nations Human Development index.

When asked about the FIFA (International Federation of Football Association, in English) and its motives in relation to the Cup, Jorge grinned and then made the universal gesture for money with his hands. “Someone is profiting from this World Cup, but it isn’t me … or our favela.”

Seven years ago when Brazil was announced as FIFA’s selected host country for this year’s World Cup, Brazilians celebrated in the streets. The country’s then forward-looking President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva was in the midst of an economic boom that had catapulted the Brazilian economy into seventh place among the world’s largest economies. During the same time FIFA officials were greeted by what they proudly described to the media as “spontaneous celebrations” by Brazilians, polls revealed nearly eighty-percent support for the hosting of the Cup.

The subsequent announcement in 2009 that the Olympics would also be held in Brazil two years after the 2014 World Cup only compounded the excitement. By all accounts, Brazil was abuzz with anticipation.

In this election year, however, support for both hosting the Cup and the incumbent President Rousseff, who hails from the same Worker’s Party (PT) as her popular predecessor, have plummeted to low levels. Contrary to nearly anyone’s expectations, polls have demonstrated that most people in the very country that has enjoyed more World Cup victories than any other no longer wanted to host the tournament whose final match played out July 13.

Why the drastic change in public opinion, over a game Brazilians clearly adore?

Collapsing Promises

“It was like an earthquake. The ground shook violently,” Daniel Magalhaes told reporters huddling around the scene of an accident. “I heard a deafening sound. I looked and saw the collapsed overpass.”

Headlines around the world were instantly posted in the news media on July 3 when a bridge located in the host city of Belo Horizonte and near the Mineirao Stadium where World Cup matches were held collapsed on top of a bus and passenger cars in a gruesome scene captured by video. Hanna Cristiana Santos, a bus driver, and Charlys do Nascimento, aged 24 and 25 respectively, were instantly killed. Almost two dozen more people were injured. The construction company, the city announced, would pay for the funeral arrangements for the two families.

The Belo bridge collapse was not the only thing that collapsed. The very next day, Colombia’s defender Juan Camilo Zúñiga recklessly jumped into the air for a loose ball and came crashing directly down on none other than Neymar Jr., Brazil’s great hope for the World Cup. Neymar told his teammate, “I cannot feel my legs,” after suffering Zúñiga’s blow.

For many Brazilians, their hopes of Brazil winning the World Cup were significantly dented if not dashed altogether with Neymar’s and Thiago Silva’s–the team captain who was disqualified because of yellow card accumulation–absence. As it turned out, the seleção wound up suffering a historic defeat in the World Cup’s most lopsided knockout round loss ever. The Germans, who ultimately won took home the Cup trophy, mercilessly pounded against a brittle Brazilian defense and won 7-1. Adding to the cruel irony was that the defeat occurred in Belo Horizonte–the same place where the bridge collapsed.

The subsequent third place match added to the pain, as Brazil was humiliated again 3-0 at the hands of Holland. The match was played in Brasilia, a city that doesn’t even have a first division Brazilian soccer team and rarely can attract attendance to second division matches of more than a thousand people. Now the capital will have to struggle to find a use for the FIFA-standard stadium.

Many observers before the World Cup agreed that one of the few ways that FIFA and the Brazilian government could salvage a losing public relations front when it came to hosting the event, was for Brazil to win the Cup on its home turf and in the same stadium where it suffered its most stinging historic defeat. Brazil lost to Uruguay in the 1950 final (known as the “maracanaço” to Brazilians, a reference to Rio’s Maracanã stadium, which then had a capacity to hold almost two hundred thousand people). But alas, there would be no final in Rio. Instead, Brazilians rioted in the city’s streets, where mass robberies were reported especially in the famous Copacabana beach district.

While no Brazilian expected the trouncing the team suffered against Germany, probably few Brazilians were surprised that one of the unfinished infrastructure projects promised for completion by the World Cup’s start wound up literally killing several of its own people. Fewer than 10 of the 56 infrastructure projects racking up billions of dollars in public expenses were completed on time for the tournament.

“Nearly nothing about hosting this World Cup surprises me anymore,” says Leonardo Silva, a 59 year-old cab driver who has long been working in Natal, a tourist-driven beach city that hosted the Me xico and United States matches.

On FIFA’s Terms

Before the World Cup started, the atmosphere in many cities in Brazil was noticeably dialed down from what one would have expected in 2007. One after another, local press accounts described the pre-tourney atmosphere as “lackluster” and “way less supportive than in previous World Cups hosted abroad.”

Widespread protests, attracting millions of angry people raging into the streets in cities across Brazil, surged a full year before the World Cup even began. International press coverage largely focused on a bus fare hike as what sparked the protests. Gil Castello Branco, the director and founder of Open Accounts, a Brasilia-based NGO that serves as a budgetary watchdog group over the Brazilian government, pointed out that the issues ran deeper than the bus fare hike and included the World Cup.

Widespread protests, attracting millions of angry people raging into the streets in cities across Brazil, surged a full year before the World Cup even began. International press coverage largely focused on a bus fare hike as what sparked the protests. Gil Castello Branco, the director and founder of Open Accounts, a Brasilia-based NGO that serves as a budgetary watchdog group over the Brazilian government, pointed out that the issues ran deeper than the bus fare hike and included the World Cup.

“You saw the protests last year, right, Andrew?” asked an impassioned Castello the day after the bridge collapsed. “The Brazilian people were demanding to get public benefits out of the event. They said they wanted FIFA-standard schools to be built for Brazilian children, just like the stadiums.”

The nation’s youth, who showed up in droves to protests last year and at the start of the tournament, continue to be a glaring developmental hole for Brazil. While close to 40 million Brazilians have left poverty during Brazil’s rapid developmental climb since the turn of the century, the youth are often left out of this picture when it comes to long-term and stable employment. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, close to 42% of young people have to depend on the precarious informal economy for a livelihood.

“Promising 12 stadiums in 12 cities to FIFA was too much to offer. These stadiums, especially in Manaus, Brasilia, Cuiaba and Natal, won’t ever be used to their capacity,” said Castello.

Other experts, such as Claudio Weber Abramo, the Executive Director of Transparency Brazil, echoed Castello’s sentiments. “FIFA makes its demands and then they arranged to have twelve different places to hold games. This was simply too much. In some of these cities, like Manaus, there was no professional football there whatsoever. It is ridiculous.”

Apparently, Brazilian officials did not pay heed to the words of one of Brazil’s most famous icons–singer, song-writer and poet Chico Buarque–who warned, “You cannot place your faith in a football stadium – that’s the lesson that sunk in after 1950.” He was referring to the belief that a huge stadium filled with Brazilian fans would lead the team to victory. His statement could be applied to the politics of hosting mega-sports events as well.

As early as the Confederations Cup, the World Cup warm-up tournament held in the host country the year before the big event, the press began reporting on worker fatalities and construction delays with cost overruns in the billions of dollars. Millions of Brazilians seemed to remember Buarque’s words when they took to the streets. Neymar, who rarely voices any political sentiments, announced on Facebook that, “From now on, I will enter the field inspired by this movement,” explaining further that he desired to see a, “Brazil that is more just, safer, healthier and more honest, which is the obligation of the government.”

Even the face of Brazilian football, the legendary Pelé, expressed sympathy with the protests and criticized the way public funds have been spent. “Money could have been invested in schools, in hospitals,” Pelé told the press this past May. “Brazil needs it. That’s clear. On that point, I agree with the protests,”

Plans to erect a 300-kilogram statue of Pelé before the start of the World Cup in front of the Maracanã stadium also stalled. The frustrated artist commissioned to finish the piece explained to the Times of India that the project was “politically abandoned” a few days after Pelé’s remarks.

As the tournament got underway, the rap sheet of World Cup-related problems was already lengthy. Neil de Mause, co-author of Field of Schemes and a specialist in public spending utilized for private sports stadiums published an article online shortly after the World Cup began that highlighted the worst social and political problems caused by the World Cup:

- Spending on World Cup preparations ballooned to $15 billion, swallowing entire regions’ development budgets and helping spark widespread strikes over low wages.

- An estimated 200,000 people were evicted from their homes, either to make way for World Cup construction projects or because their neighborhoods were designated “high-risk” areas.

- Eight workers were killed in construction accidents during the rush to have new stadiums ready in time for the cup — despite which the stadiums were still decidedly not ready.

- Planned new schools, hospitals and other public projects that were initially promised fell off the construction agenda once the budget ran dry.

- The government spent an additional $900 million on police technology, including surveillance drones, to ensure that anyone upset about all this didn’t cause too much of a ruckus.

De Mause explained that these problems were part and parcel of a “sports model designed to socialize all of your costs so that you can privatize all of your profits. It is a lot easier to make a whole lot of money if someone else is paying your costs. That’s something you see whether it is the New York Yankees or the World Cup.”

Should these problems have been anticipated? Chris Gaffney’s answer is an adamant “yes.” Gaffney, a visiting Professor at the Universidade Federal Fluminense, has been living in Brazil for a half a decade and studies the way mega-events, such as the World Cup, are run and managed.

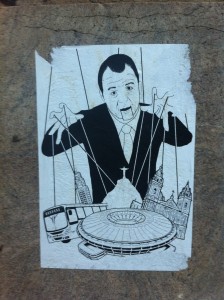

“Public officials could have demanded FIFA to ask for more from their corporate patrons,” Gaffney explained. “But this isn’t about wise use in public money. It’s an extractive business model in which FIFA articulated its business interests and found willing partners among Brazilian governmental and economic elites.”

The picture of an “extractive” business model that Gaffney paints is similar to how Professor Bent Flyvbjerg, another specialist on mega-events, from the Oxford School of Business, describes in his research findings. Particularly when it comes to Olympic and World Cup spending, Flyvgjerg said that, “costs wind up being significantly higher than what was initially estimated… while on the benefits size, we found the opposite. We found that the actual benefits are lower. So you get this double whammy with higher costs and lower benefits, which any businessman would say is not a good situation.”

Flyvgjerg added, “We find in general that politicians like to build flashy monuments and certainly something like expensive FIFA-inspired World Cup stadiums are an example of that. Unfortunately, we find that it is very difficult for officials to find a sensible use for these stadiums after the World Cup is over.”

Not a good situation for the public, in particular, added Weber. FIFA “says I want this and that. That is their role. And they get what they ask for, at the cost of the public.”

The bidding and negotiating process behind what is offered, asked for, and agreed-upon remains clouded in mystery and secrecy. Weber noted, “Everything is confidential. FIFA and the Brazilian organizing committee can and did hide whatever they wanted.”

That is the reason why, as Gaffney explained, “The bid book for Brazil hosting the World Cup has never seen the light of day. The bid was given by disgraced former FIFA Vice President, Ricardo Texeira, to FIFA chief Sepp Blatter in 2007 and the document never surfaced publicly.

What has surfaced since FIFA awarded Brazil the bid and the government began the preparations has been FIFA-related public spending and projects.

In 2007, Lula made lofty promises and voiced high expectations of public-private partnerships in the aftermath of Brazil being chosen as a host country. He promised, “Stadiums will be completely built with private money. Not one cent of public money will be spent.” During the same time, excited officials from the Brazilian Football Federation echoed Lula’s claim. However, because of the failure of public-private plans to ever come to

fruition, public spending exploded and a significant paper trail followed, one that Weber and Castello have been closely following.

In the case of the country’s capital, Brasilia, a municipal auditor’s court released a 140-page report detailing over $275 million in over-spending for a $900 million stadium-building project for the World Cup host city. The stadium is the world’s second most expensive among soccer venues standing in sharp contrast to the lack of a professional team to fill the seats there after the Cup ends.

For Weber, even with the revelations of the scathing Brasilia audit report, there are still sharp limits to what is known thus far. “The actual totals on over-spending on stadiums and corruption related to it is already bad and it will be much worse than what people know and think right now.

Carol Campos, a 22 year-old Brazilian woman who attended many of the protests against the Cup, railed against another lavish stadium built for the Cup up in Natal. She asserts that the expensive arena will have no clear use after the Cup.

“It really is a beautiful stadium, if you see it from the sky, it looks like a sand dune, which are typical here in Natal. But the thing is, it’s a crazy situation. They built a whole stadium for four games. Four games!”

Bidding for Trouble?

The bid for the 2014 World Cup, which by FIFA rules had to be held in Latin America this year, had one entrant: Brazil.

Some experts speculate that the reason why Brazil had no competition on the bid for the Latin America-designated FIFA rotation is that there’s a political cost for politicians wanting to build flashy monuments bearing their name, in addition to the economic costs. In political terms alone, and certainly in Brazil’s case, hosting mega-events has proven to be risky and unpredictable. The way matters are shaping up for President Rousseff as of late is a strong case in point.

Brazil’s close association with FIFA and its slowing economy have not won political points for President Dilma Rousseff. During the current World Cup, FIFA has stirred controversy. Scandals regarding reports on bribery being a factor in Qatar’s successful attempt to win the 2022 World Cup bid. The awarding to Qatar raised the eyebrows of football observers the world over, in no small part because of the scorching desert-like temperatures in Qatar during the summer months the Cup is held. Other scandals included one where a FIFA official was implicated in a Brazil-based ticket-scalping ring that reaped millions of dollars in resale profits, and an alleged match-fixing scandal, implicating players and possibly officials from the Cameroon squad.

In Brazilian politics, an Associated Press investigation published last month revealed that companies receiving publicly funded and FIFA-related construction projects turned around and raised their election campaign donations to the same public officials who awarded those contracts. In some cases, donations leaped by over 500% higher than their previous donations.

President Rousseff’s approval rating fell to a paltry 38% in April 2014 and at the start of the World Cup, was hovering around 34%. Nevertheless, Rousseff’s closest challenger for the October presidential election is still many percentage points behind her in terms of how they are polling.

While President Rousseff may be able to weather her lowered popularity in the face of a disastrous World Cup, governments – particularly those of newly developing or under-developed economies – may now think twice about hosting the World Cup.

Such second thoughts may be particularly weighty if the people in the host nation have any political decision-making power over the decision.