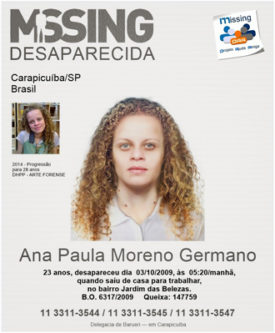

Sandra Moreno’s weary eyes reveal the struggle she faces daily. Her daughter, Ana Paula, disappeared in 2009, and since then it is like the clocked stopped for her while others moved on with their lives. Ana Paula was 23 years-old at the time. She left home in the early morning to catch a bus to work and didn’t return.

Sandra Moreno’s weary eyes reveal the struggle she faces daily. Her daughter, Ana Paula, disappeared in 2009, and since then it is like the clocked stopped for her while others moved on with their lives. Ana Paula was 23 years-old at the time. She left home in the early morning to catch a bus to work and didn’t return.

For Moreno, the uncertainty has been torture. All kinds of ideas run through her head: Maybe Ana Paula was abducted, or maybe she was killed. But whatever happened to her, her mother says that not knowing is worse–it squeezes her heart and has led to a battle with depression. She takes tranquilizers, since every time she recounts her ordeal, she relives it.

According to The Brazilian Forum on Public Security from 2018, at least 82,684 people disappeared in the country in 2017. The state of São Paulo leads with 25,200 disappearances, followed by Minas Gerais with 8,878 and Santa Catarina with 7,752. And this is not counting the underreporting, which makes compiling data on missing people extremely difficult.

The Brazilian Forum on Public Security or other agents haven’t released numbers on the relation between disappearances and gender. Federal Prosecutor Dr. Eliana Vendramini who conducts São Paulo’s Program for the Localization and Identification of Disappeared Persons (Programa de Localização e Identificação de Desaparecidos, PLID) stated in 2017 that in São Paulo the most common profile for missing persons is black teenagers hailing from the urban periphery, which also coincides with the most common profile of homicide victims.

In some cases of disappeared women, the disappearances can be related to human trafficking as in other parts of the world. UN data shows that two-thirds of human trafficking victims are women, while most of the traffickers are men. Nearly 80 percent of victims become sex slaves, while 18 percent work in forced labor, including agriculture, construction, the food industry. In Brazil, human trafficking occurs mostly in the north and northeastern parts of the country and border cities, but it’s unknown how it relates statistically to race, ethnicity, social class, gender, sexuality, nationality and immigration status due to the lack of specific data.

It can be misleading to make assumptions regarding the relationship between disappearances of women and sex trafficking. Anthropologist Laura Lowenkron warns that the so-called “vulnerability factors” in human trafficking are being used globally to justify the enforcement of controlling immigrant flows from poorer regions of the globe, rather than guaranteeing their rights and protecting them from violations. For the scholar, it is important to not treat all mobility associated to sex w ork with the crime of human trafficking crime.

ork with the crime of human trafficking crime.

To finally fill some of the legal gaps in dealing with the crime, on Feb. 20, the Brazilian Senate approved the National Policy on Searching for Missing Persons elaborated by former congressman Duarte Nogueira. It is pending on another vote. The policy establishes articulated actions between law enforcement and political and regional powers and the updating of the National Database of Disappeared Persons (Cadastro Nacional de Pessoas Desaparecidas, CNPD).

The National Database was created in Dec. 17 2009 and introduced Feb. 26, 2010 with the governmental site for missing people (www.desaparecidos.gov.br). It did not work for seven months and managed to register only around 370 minors until the government decided to take it down. Currently it is operating, but with a very limited capacity.

During former President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration, the 2005 Search Law defined that the police should start investigations on the whereabouts of children and adolescents right after being notified. For adults, the searches start 24 hours after being reported missing–it used to be 48 hours.

The city of São Paulo is the third largest in the world and the richest in South America. It is a major center for business, high-end restaurants and hotels, culture and lavish nightlife, but Moreno lives in the periphery, in the city of Carapicuíba. Her home is in a lower-middle-class, blue-collar neighborhood, with washed-out painted, small houses. Ana Paula’s bedroom is kept just as she left it.

After coming to grips with her pain, in 2011 Moreno started to collect signatures demanding a national law that would enable more specialized police stations for searching for the disappeared, such as in São Paulo. Disappearance isn’t classified as a crime, so it is often treated as though the person were temporally missing, and the police aren’t obliged to start searching procedures.

Asked if Brazilian women are more prone to disappear and why they disappear, Moreno reacts with indignation. “If we had more accurate and realistic data, we could understand if it is men or women who disappear most and the many reasons behind it.” She notes that Brazilian authorities and the media treat the issues of forced disappearances and human trafficking as a novelty, which results in misinformation and a lack of progress in understanding the crime.

Asked if Brazilian women are more prone to disappear and why they disappear, Moreno reacts with indignation. “If we had more accurate and realistic data, we could understand if it is men or women who disappear most and the many reasons behind it.” She notes that Brazilian authorities and the media treat the issues of forced disappearances and human trafficking as a novelty, which results in misinformation and a lack of progress in understanding the crime.

In her organizing work, Moreno promotes protests in the streets of Carapicuíba using art. She frequently lectures on the subject in colleges and has traveled to the capital Brasília to meet with politicians and hold them accountable for the rise in disappearances.

While she struggles to make her voice heard, many public figures and celebrities have approached with promises. They take photos and post about the issue in social media, but like the politicians they soon tend to vanish. “(In this quest) we are like parentless children”, Moreno notes. She states that her activism has put her own safety at risk. Those searching for disappeared children and relatives have endured not only ostracism, but also revictimization and threats.

Moreno is willing to run the risks to find her daughter, or at least, the truth.

Brazilian journalist Gabriel Leao is a regular contributor to the CIP Americas Program, specializing in gender issues and Brazil.