The Haunting Agony of a Nation

The Haunting Agony of a Nation

The incident has become a turning point in Mexican history: A year ago on the evening of Sept. 26, 2014 a group of 100 students from the Raul Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa were attacked in Iguala, Guerrero by Mexican security forces.

The students were attempting to secure buses to travel to Mexico City for the annual march to commemorate the Oct. 2, 1968 massacre of students in Tlatelolco. A series of separate attacks on the students by Iguala and Cocula police and armed commandos lasted into the early morning hours of Sept. 27, 2014. The army stationed nearby did nothing to protect the students, and delayed medical attention to the wounded.

Six people were left dead that night, including three Ayotzinapa students. One student remains in a coma, and 43 students were forcibly disappeared by Mexican authorities. To this day, the whereabouts of the students and why they were taken remains a mystery.

Rural Schools Under Attack

Rural Schools Under Attack

It was not the first time Rural Teacher College students have been attacked by government forces. The Rural Teaching Colleges provide access to education for impoverished farm families and for more than eight decades they have been systematically undermined and violently attacked by the state for their socialist pedagogy and revolutionary approach to education.

A report by the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center notes the deep roots of the Justice for Ayotzinapa movement, and the Rural Teachers Colleges established in Mexico in 1917. In the years following the Mexican Revolution, the schools were founded to “create citizens that are conscious of their rights”. Over the years many of the colleges have been forced to shut down due to cut off of funding and the militarized suppression of their defense of their pedagogy that challenges the dominant neoliberal policies of the government. Only 17 out of 36 original Teachers Colleges remain open.

The traumatic events in Iguala and the inadequate, even corrupt, state response has provoked mourning and indignation. The disappearances shocked many into asking themselves what kind of a society allows students to be murdered, tortured and forcibly disappeared. But it also brought a renewed awareness of the values embodied in the Rural Teachers Colleges and their brand of education for social change.

The attacks, assassinations, and disappearances of the Ayotzinapa students awakened the consciousness of Mexico, and much of the world, by connecting various fights for justice that all share this widespread commonality: a rejection of state-sponsored violence, and an affirmation of the power of rising up together to fight for a world that values human lives.

Transforming Anguish into Action

Transforming Anguish into Action

What progress has there been in seeking justice and finding the 43 students? Any advances toward justice and revealing the truth have been driven by the parents, families, and allies of the 43, rather than by the state whose job it is to investigate and prosecute. The Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) recently published its expert report exposing the government’s conclusions of the Ayotzinapa case are inconsistent and unsubstantiated and include misaligned testimonies, obstructed crime scenes, delayed response to start searching for the disappeared students and insufficient and tampered evidence. The state’s investigation has failed to provide a motive behind the forced disappearances and attacks. The evidence presented by the state has not supported any of its four official versions of the crime reviewed in the report.

The attacks have had a severely traumatic impact on the surviving Ayotzinapa students and the victims’ families. Some of the surviving students have since dropped out of the Ayotzinapa Teachers College out of fear. All are coping with the post-traumatic stress of the attacks and the unbearable fact their peers and friends are still missing.

Families of the 43 disappeared students have been torn apart. Parents of the 43 have relocated to the Ayotzinapa College, leaving behind jobs and other children to dedicate all their time, energy and heart to the search for their missing sons. Many families had little resources before the attacks, but now they have even less as they have had to abandon work and pay to travel to meetings with government officials and incur other expenses. With a missing piece of their family, they are not whole. Focusing their efforts on the search for their children and justice has not only hurt the financial stability of the families, but many emphasize that they are not eating regularly and illness is common.

“To not know anything…of him…where he is, how he is, what happened to him, well the truth is, we feel…the strong pain, the pain is so strong. This pain really hurts,” states one of the parents of the 43. The search for the 43 and the collective space created at the Ayotzinapa College, has given the parents hope and an outlet for this pain. Without governmental support or advances in the investigation, the parents have taken the search for their children into their own hands. Their desperation and unwavering dedication to the search for their children and for the truth has touched the Mexican and international community, making the parents the soul of the movement for justice.

As Epifanio Álvarez, a father of one of the 43 disappeared students, told the Americas Program, “A child cannot be forgotten…we will fight to the end, with the support of you who feel what we are going through. Sometimes at two o’clock in the morning we remember and we start to cry. With your support we will continue without stopping.”

You are not alone!

You are not alone!

The first 72 hours of missing persons’ cases are critical to the chances for success. Did the Mexican state comply with search standards and protocols? Not then, or since. It was the parents who started the search on Sept. 27, and it was the parents and surviving Ayotzinapa students who created the list of missing students by Sept. 30, 2014. It was teachers who showed up the night of the attacks, and continued to organize and support families and the Ayotzinapa community. From the beginning the parents, teachers, and students organized, and took action to uncover the truth, search for the missing 43 alive, and demand justice.

The night of the attacks, Ayotzinapa students activated social media networks to publicize the emergency. From the beginning, people began to organize to support them. The National Coordinating Body of Education Workers (CNTE), the democratic current of the official National Union of Education Workers (SNTE), unified teachers who brought food the first weekend to the parents of the 43, and started coming every Saturday to see how they could support them. The CNTE helped parents build out their national and international networks to inform the world about what had happened, and build solidarity in the search for their sons and justice.

The indigenous group of Chiapas, the Zapatistas, offered their cross-cultural comradery in the first week. Their first act of solidarity was a special communiques from the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee of the National Zapatista Liberation Army’s (EZLN) on Oct. 7 stating, “You are not alone” and calling for organized actions. The following day, 21 cities and 15 countries participated in actions calling for justice. From there the Justice for Ayotzinapa movement spread across Mexico.

The crimes of Ayotzinapa mobilized the people of Mexico for three main reasons:

The crimes of Ayotzinapa mobilized the people of Mexico for three main reasons:

Being a student is not a crime. Students at Teachers Colleges came together as they have always done, and as news spread to students of other universities they too mobilized. The students maintain that the attack against the Ayotzinapa students in Iguala was not isolated and was an attack on all students. They assert that Peña Nieto’s education reform would eliminate schools such as Ayotzinapa and the move to privatize education would restrict access to education. For them, acts of state violence against youth and students reveal that the government does not want an education system that empowers the younger generation to lead change.

Education can be a tool for empowerment, but it can also be an instrument to control and repress society and movements. The Ayotzinapa attacks made it known that students and youth are the targets of state violence. This has brought the students and educators to the streets, because they could be the 44th.

The love of a parent. The tangible and inconsolable pain the parents of the 43 feel has transcended families, cultures, and even borders. At the same time the ferocity with which the parents advocate for justice, and search for their children, and the sheer number of Ayotzinapa parents has spotlighted this case, and ignited support. Many other parents of disappeared in Mexico have come forward and organized alongside the parents of the 43, helping the nation make connections that this is a systemic state-sponsored war against the people.

This is critical because it lays the foundation for families of disappeared to organize and hold the government accountable to prevent any more forced disappearances. The Mexican government reports that there are over 25,000 disappeared people in Mexico, but human rights experts estimate that this number is much higher since the country does not currently have a national reporting system, legal practices for forced disappearances, or missing person best practices in place.

The nation empathized with the parents–a common phrase at demonstrations is, “He could be your son.” One mother of the 43 stated, “We all went to [the first protest] sad and really pensive. We did not know exactly what we were going to do. We got off [the bus] at a crossroad in Chilpancingo. I remember there were many people who began to shout, ‘You are not alone! You are not alone!’ And the only thing I could do was cry.” The parents cannot forget their sons, and because of their voices, neither can the world.

Your rage is ours. The attacks on the Ayotzinapa Normal students were the last straw for groups targeted by state violence. Instead of viewing cases in isolation, a collective indignation and determination to transform the country has grown so large that it can no longer be contained by the state. Youth, farmers, women, indigenous, laborers, LGBTIQ, journalists and environmentalists all recognized the common thread of corruption and impunity that links the state and organized crime. The rage is now owned by the people, who use it as fuel to fight for justice for the 43 students and all the oppressed.

Omar Garcia, one of the Ayotzinapa survivors and spokesperson for the movement states, “The pain that we’re feeling is a unique opportunity to increase the pressure, to achieve a broad mobilization that transcends Ayotzinapa and Guerrero, that can finally put an end to the intolerable situation of violence and impunity that we all have been experiencing in Mexico for years.”

Ayotzinapa, the Soul of the Global Movement

Ayotzinapa, the Soul of the Global Movement

The Justice for Ayotzinapa movement was able to cross borders, and gather global support by leveraging existing international solidarity networks from other similar struggles. Other movements and people recognized their pain and struggles reflected in that of the Justice for Ayotzinapa movement. Thus, the phrase, “We are all Ayotzinapa!” can be heard in the streets across the globe. The Nicaraguan Sandinistas, EZLN, #YoSoy132, migrant communities, Chicanos and Latinos in the U.S., and many others embraced the Justice for Ayotzinapa fight as one of their own.

There is also solidarity with other countries that have experienced similar fights for transformation such as Egypt, Tunisia, Greece, and beyond. Likewise, Latin American countries such as Argentina, Colombia, and Guatemala, that have experienced mass forced disappearances during repressive dictatorships (also instigated by U.S. foreign policy, just as in Mexico today) embraced the families of the 43 disappeared students. Meeting the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo movement in Argentina and witnessing their unwavering commitment to search for their children and justice for the past 40 years gave strength to the parents of the 43 students.

The tragedy of Ayotzinapa also raised awareness of the U.S. role in the drug war, and state-sponsored violence in Mexico through the Merida Initiative. The Merida Initiative began by ex-President Bush in 2007, and extended indefinitely by President Obama, has provided some $3 billion towards the war on drugs in Mexico. The result of this funding has been increased militarization in a battle ostensibly against the drug cartels but that has left 100,000 dead, more than 25,000 forcibly disappeared, and increased attacks against migrants, women, and other vulnerable populations. This exposes one of the roots of the Ayotzinapa attacks, that of U.S. government policies and funding that have wedded the Mexican government to organized crime in the name of fighting the war on drugs.

For years, U.S. organizations grouped in the Mesoamerican Working Group (MAWG) and others have organized to demilitarize U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. These groups have condemned the Merida Initiative and its inherent implication to the attacks against the students. Arturo Viscarra, the Advocacy Coordinator for School of Americas Watch, a member of MAWG, told the Americas Program that “there is a consensus that militarization is making things worse. That the state does not have a real interest in really defeating organized crime, they have more of an interest in fighting organized people.”

During a press conference in November, Mexico’s Attorney General, Jesus Karam Murillo, who has since stepped down, responded to questions about the state’s claim that the students were burned at the Cocula dump with, “No more questions. I’m tired.” This instigated the twitter trend of #YaMeCansé (I’m tired) to publicize the crime of Ayotzinapa and the corrupt and careless response of the state.

U.S. and Chicano activists took it a step further to denounce the U.S. government role in Mexico’s violence by beginning the #USTired2 movement. This movement, in solidarity with Justice for Ayotzinapa, has mobilized students, Latinos, migrants, and many others in the United States to demand an end to the Merida Initiative, promote peace, and demand transparency. The #USTired2 movement organized across 50 cities in the United States in early December of last year.

Over the past year, the families and peers of the Ayotzinapa 43 have traveled across Mexico and the world in caravans broadcasting the state-sponsored crime, and building solidarity to organize for justice. From Ferguson in the U.S. to Paris, France, to São Paolo, Brazil a familiar thread emerged: state violence and police brutality are rampant. By Oct. 22, 2014 the caravans had reached 50 cities in Mexico, and 20 cities around the world. In March, the families and peers of the Ayotzinapa 43 traveled to 50 U.S. cities, and by April the Ayotzinapa caravan had arrived in Canada. In the months of April through May, the Euro-Caravan visited 19 cities in Europe. Then May through June a caravan visited countries throughout South America.

What the Justice for Ayotzinapa movement does is connect these struggles so that there is a global collective fighting for a world that does not allow these acts of violence and repression to occur. The movement has taught us that, “just as they have globalized repression, we must globalize resistance.”

Transformation, Not Martyrs

Transformation, Not Martyrs

The Justice for Ayotzinapa movement has gathered people to march in the streets, pressure governments, and create art with consciousness, all to find the 43 disappeared students and to stop systemic repression in the world. What is different with the Ayotzinapa movement? How has it succeeded, and what must happen next to obtain justice and truth?

The Justice for Ayotzinapa movement crosses borders and connects movements, it has thoughtfully been a movement rising up from the bottom, and refusing to be dictated to by those at the top of the hierarchy in society. In this way, it has united people with collective oppression and rage, and reclaimed humanity and power. When connecting with local organizations and activists throughout Mexico or abroad, the movement has focused on being driven by the locals who know the context best, and who have been building their organizing roots for years. The movement has relied on these solidarity networks to provide housing and food for the families and peers of the 43 as they travel around the world in Ayotzinapa caravans.

The Justice for Ayotzinapa movement has brought old and new movements under its umbrella. Indigenous community police in Guerrero have joined families in the search for the students–a dangerous mission as they comb terrain under control of organized crime and corrupt armed forces. Artists and musicians have collaborated to creatively denounce state violence while seeking justice and truth. The use of songs, graphic arts, dance and street theater call attention to the state crimes and mobilize communities. Activists have collaborated on social media using hashtags that have empowered and broadened the movement.

The National Popular Assembly (ANP) was created out of the movement and has organized Global Days of Action every 26th day of the month that passes without the 43 students returned. Ayotzinapa student activist Omar Garcia told the Americas Program that it is time to do more than march in the streets. “We cannot walk the same path as always. We have to do something different and we have to build it ourselves.” This is exactly what the Justice for Ayotzinapa movement is doing, along with the global community that is an ally fighting for change and justice.

Garcia stressed the importance to not turn the 43 disappeared students into martyrs, because that implies that they are dead and the families and supporters insist, rightfully, that until evidence is produced to the contrary the students must be assumed to be alive. Also, to label the students as martyrs “to champion a greater cause” pushes an agenda that undermines the cause and objectives of the movement. The movement seeks to find the 43 students alive, to end the corrupt relationship between the state and organized crime in Mexico, to end systemic violence and ensure that atrocities like this never happen again in Mexico or anywhere in the world.

To achieve these aforementioned goals of the movement, the movement has identified several necessary steps:

Implement the GIEI report’s recommendations immediately. This means reinvestigating the crime, the facts, the motives, and who gave the orders. It is vital that the state restart the search for the students alive. It also calls for an investigation of the obstruction of justice and the state’s role, including the acts of the C-4 communications and command center that was monitoring the students the night of Sept. 26.

Additionally, national systems should be created for documenting and handling cases of forced disappearances, including processes to include and support families of disappeared persons such as communicating updates to families of victims first before media, involving them in the search process, supporting them economically, medically, and even their safety. It is also crucial for the Mexican government to pass the Law on Forced Disappearances. To pressure the government to implement these recommendations sign this petition.

Do not forget about the 43 students, maintain the momentum of the movement. Remember their faces, names, stories, and the families and friends that ache in misery for not knowing and desperately needing their return. Empathy is critical; if the world we live in allows this injustice to happen then it could also happen to us or to our loved ones. These are 43 people who have their whole lives ahead of them, and with their absence, and the absence of truth, what is left behind is broken communities and families. If these individuals are forgotten or dehumanized, then the parents and peers will be left alone in their search for justice. Remember also that there are thousands more disappeared in Mexico, and violent attacks every day. Remember that each of these lives has value, and should be respected. To establish this as a norm in our globalized society, we must continue fighting for the 43 and the many more.

Do not forget about the 43 students, maintain the momentum of the movement. Remember their faces, names, stories, and the families and friends that ache in misery for not knowing and desperately needing their return. Empathy is critical; if the world we live in allows this injustice to happen then it could also happen to us or to our loved ones. These are 43 people who have their whole lives ahead of them, and with their absence, and the absence of truth, what is left behind is broken communities and families. If these individuals are forgotten or dehumanized, then the parents and peers will be left alone in their search for justice. Remember also that there are thousands more disappeared in Mexico, and violent attacks every day. Remember that each of these lives has value, and should be respected. To establish this as a norm in our globalized society, we must continue fighting for the 43 and the many more.

Hold the U.S. accountable, and dismantle similar state-sponsored violence in the world. For those of us from the United States, it is critical that we hold our government accountable for its responsibilities in the Ayotzinapa crimes, and the violence caused in the so-called war on drugs. The U.S. government has a history of funding and militarizing other countries, and this must stop now. Instead of pouring billions into the Merida Initiative, and focusing on arming and training Mexican security forces, the U.S. should focus on funding rehabilitation for drug addicts, and the regulation of drugs in its own country. U.S. aid for the drug war has exacerbated violence and eroded rule of law, creating greater alliances between organized crime and the government in Mexico while the U.S. market for prohibited drugs provides a lucrative source of income for criminals.

To condemn the state of Mexico is not enough. As US citizens, we must condemn our own government and its role in facilitating the crimes. The terrible impact of our militarized policing approach can be seen in Ferguson, Baltimore, New York City, Oakland, and practically any city or town in the United States. It is important to make these connections, and understand that the fight to end the Merida Initiative is also linked to the fight to end the police state in the United States.

Continue to insist on education for human development, not big business. Many Rural Teachers Colleges have shut down over the years, some Ayotzinapa students have dropped out, and many other young people are discouraged and even fearful to attend. What does this do to a society? If a corrupt elite gains control of the education system, then it gains control of future generations. People should continue to reject privatization and neoliberal reforms in education, and call for the implementation of education for social justice. These outrages also call for, as the GIEI report states, the implementation of human rights education at all levels in Mexico from security forces to the youth.

Healing as a community, and transforming society. Even when justice and truth is attained, how does a community move forward? Healing is an important part of the process of transforming a society. As the GIEI report recommends, it is crucial that projects of historical memory and reparations are carried out so that the country can heal and to ensure that these crimes are never repeated. What the families of the 43 and all the disappeared in Mexico and beyond really need to move forward and heal is the return of their children and to know the truth of what happened. Love, solidarity and memory are all key ingredients for individuals and communities to heal collectively. If wounds remain unattended, the result is disastrous for society and impedes the process of change.

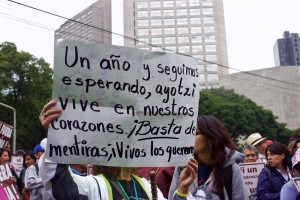

This past Saturday, September 26 marked one year since the horrific attacks against the Ayotzinapa student teachers. Thousands united in the streets in Mexico City and around the world for the Global Day of Action to express their outrage, and demand justice and truth. But the fight does not end there; the movement must persevere and continue to organize for the 43 victims, and the many more in Mexico and the world.

Nicole Rothwell is an intern for the Americas Program and writes about global social movements, education, and human rights in the region.

Photos by Nicole Rothwell