The sum of the sovereign debt emissions by all of the world’s treasuries constitutes an enormous financial market concentrated in a few principal currencies and legal jurisdictions. The money that circulates in these markets is the world’s government (sovereign) debt. These bonds are typically bought by the private sector, but are ultimately paid back (both the principal and the interest) by local taxpayers in the borrowing States. Investors (bond buyers) profit from regular interest payments and an eventual repayment of the principal capital sum. Bonds (or gilts as they are called in the UK) are considered a safer investment than shares in public companies and are often bought by pension funds.

The sum of the sovereign debt emissions by all of the world’s treasuries constitutes an enormous financial market concentrated in a few principal currencies and legal jurisdictions. The money that circulates in these markets is the world’s government (sovereign) debt. These bonds are typically bought by the private sector, but are ultimately paid back (both the principal and the interest) by local taxpayers in the borrowing States. Investors (bond buyers) profit from regular interest payments and an eventual repayment of the principal capital sum. Bonds (or gilts as they are called in the UK) are considered a safer investment than shares in public companies and are often bought by pension funds.

Or at least that is how things used to work.

Like many other sectors in the financial services industry, bond markets have also become distorted by risk derivatives and the risky behaviour they encourage. This has brought this once stodgy and conservative investment sector to the attention of high-risk hedge funds. Welcome to the brave new world of sophisticated bond trading, a speculative remake of the original introducing vulture funds, experimental actors with unsavoury appetites, and also featuring the seat-of-the-pants derivatives traders in credit default swaps (CDS).

The financial press tells us that the global bond market is facing a new crisis. It would seem that the inability of the European Troika [1] to fix the sovereign debt crisis in the periphery is now old hat. US sovereign debt—between twelve and seventeen trillion dollars (depending on how it is calculated) — is multiples of all of the debt of the Third World, but that too does not merit the attention of the financial press. Even Japan’s massive debt to GDP ratio of around 200% fails to ring alarm bells. Rather, according to the financial pundits, the principle threat to the world’s bond market comes from less than 8% of a tiny Argentine bond owned by professional bond investors.

Vulture Capital

The litigants who won the lawsuit against Argentina in New York’s Southern District federal court are hedge funds, known in bond market jargon as “vulture funds”. Vulture funds are the quintessential bottom-feeders of the secondary bond markets —they buy low and sell very high. Since private bond investors are unwilling to pay the vulture margins (some 1600% profit in the Argentine case, should they win), the vultures sue the governments who issued the bonds to buy back their own defaulted debt. Vulture funds have surprising access to the world’s financial press and spend small fortunes on lawyers, often hiring the same law firms who draw up the rules for the government bonds in the first place. Argentina’s obscure technical default is a warning to other nations not to try to restructure debt—whether the debt be illegitimate (such as odious debt) or not. This warning emanates from a financial sector which is suffering an existential financial crisis of its own making.

The Details

On August 13, 2014 Argentina’s technical default was confirmed by the determinations committee of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), a private banking association that functions as both the world’s most powerful banking lobby and as the adjudicator of both private and sovereign defaults. Argentina’s latest default is referred to as “technical” as it is the first time that a government has tried to pay the interest payments but was prevented from doing so by a legal decision. Stopping Argentina’s debt payments is both a punishment to Argentina and a warning to the World’s governments; it also means that Argentina accrues interest charges on its stopped interest payments.

This stopped payment was the result of a ruling by Judge Thomas Griesa. Judge Griesa’s home beat is the largest bond-trading zone in the planet, commonly referred to as Wall Street. Wall Street charges commissions on about two thirds of the world’s lucrative global bond trades, and also benefits from the sum of all commissions on all payments on these bonds that pass through its banks. Wall Street also includes the secondary bond markets and derivative markets on these bonds, such as banks that sell CDS bond derivatives. The City of London comes in as a distant second in this industry. London has chosen to make certain forms of vulture litigation illegal in its courts, not so New York.

The Argentine government did not appreciate Griesa’s decision. They appealed his decision to the US Supreme Court, which rejected hearing the case arguing that it did not wish to interfere in a local state ruling, albeit (Argentina argued) one with international implications. Argentina referred the issue to the International Court of Human Justice, also known as the International Criminal Court (ICC), in The Hague (Den Haag), The Netherlands. The United States does not recognise the ICC jurisdiction so this move will have little real impact.

In early September 2014, Argentina and Bolivia took the issue to the United Nations General Assembly. The UN Assembly adopted “Towards the establishment of a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring processes” (document A/68/L.57/Rev.1). 124 countries voted in favour, 11 against and there were 41 abstentions. Karel Jan Gustaaf van Oosterom, the Dutch Permanent Representative to the United Nations, commented that this “provided political support for the International Criminal Court and the work it carried out, while underlining the important relationship between the Court and the United Nations.” “The text also served to remind the world of the need to cooperate with the Court to ensure its effective functioning”, van Oosterom added [3].

Argentina also adopted a local law in September called the “Sovereign Payment law.” This highly politicized law prioritized debt payments but asserted the right to adjust sovereignty on these payments. However it stopped short of asking for a national audit on the debt. Although the new law provides for appointing a commission to analyse the debt, debt experts argue it does not allocate adequate time to the commission to complete such a complex analysis. The Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón (a former advisor to The Hague court) endorsed the law, praising it as “essential” and a “correct exercise of parliamentary sovereignty.”

What is the Big Deal?

So why does a decision made by this eighty-two year old New York judge send an entire country and the global financial world into a tizzy? Why would a small default on a Latin American bond be making headlines all across the planet? Why has Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz written that Judge Griesa has “thrown a bomb into the global economic system”? Also, and possibly more importantly, why does it matter to Argentina that by defaulting they will lose access to the international bond markets when they haven’t had access to these markets since 2002?

To discover the significance of Argentina’s default crisis, it is revealing to look into the origins of this national debt and what these borrowed funds were spent on. Also it is helpful to keep in mind that the 2014 default is the direct consequence of another (much larger) default in 2002. In 2005 Roberto Lavagna, Argentina’s Economics Minister at the time, restructured this 2002 default offering an exchange of new bonds for old defaulted bonds.[3] By stopping the payments on this restructured debt (92% ratified)—which have been paid on time for nearly ten years—Judge Greisa has created yet another sovereign debt panic.

Origin of the Debt

Argentine sovereign debt has had a long and painful history since the first million pound sterling loan made by Baring Brothers (a London bank) to President Rivadavia in 1822, but the current story of Argentine debt begins after the Cuban revolution in 1960. Following it insurgencies occurred in various South American nations in that decade. Some rebellions had direct Cuban involvement, like the failed revolution in Bolivia where Ernesto (El Che) Guevara was killed. The US launched various CIA-backed anti-communist counter-offensives to stem the rise of socialism in the Americas. Measures included Project Condor, an international telephone network in Panama used to coordinate counter-revolutionary forces between friendly governments. There was also extensive logistic, material and monetary support for various right-wing coup d’états. In South America the most significant coups began with the 1964 coup in Brazil (Goulart/Castelo Branco), but the pace accelerated in the 1970’s with Bolivia (1971, Torres/Banzer), Chile (1974, Allende/Pinochet), and the bloodiest of them all, in 1976 in Argentina, where Isabel Perón (Juan Perón’s wife) was overthrown by the junta of Generals Jorge Rafael Videla and Roberto Eduardo Viola. Tens of thousands of Argentines were disappeared.

Although assassinations and disappearances started during Perón’s tenure, the most murderous years by far in Argentina were during the junta’s reign between 1976 and 1979, resulting in rising security costs for the illegal military government. These included the direct cost of arming Argentina’s death squads for their bloody repression, –state terror directed toward the Argentine people themselves. However, even more expensive were the economic subsidies created by the junta to buy favours from national and international companies in Argentina. This public relations exercise cost $14 thousand million [2] in debt forgiveness for private companies, forgiveness that became sovereign debt. The pundits conjured up a Spanish term for this at the time: La estatización de la deuda privada, a term which was never translated to English, but which is now referred to as “socializing private debt”. There were also direct military costs incurred in the build-up to the Falklands/Malvinas war, as will be detailed below.

While the first tens of thousands of Argentines were being rounded up by death squads to be tortured and killed in covert concentration camps, the loans from multilateral organizations –—including the first stabilization loans from the IMF, arriving just days after the coup, helped keep the junta’s head above water. These early loans were facilitated with extreme neoclassical efficiency by the junta’s first minister for Economics, José Martinez de Hoz nicknamed ‘Joe.’

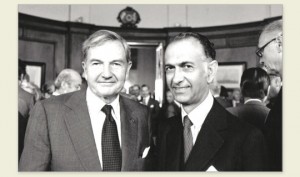

Joe was a J.P. Morgan banker and a personal friend of David Rockefeller. Many also believe that Joe was influential in the planning of the 1976 coup. He died under house arrest in 2013. The Argentine national debt never recovered from the military junta’s borrowing, which multiplied the 1976 debt of $9,700 million into $45,000 million in 1983. Despite various legal and political attempts at doing so, subsequent governments did not audit odious debt. Raúl Alfonsin, the first democratically elected President after the junta handed over power, raised questions on this issue but they were quashed. An extensive legal investigation by Argentine Judge Ballesteros found many legal problems, but subsequent governments (including the two latest Kirchner governments) have also chosen not to open this Pandora’s box of Argentine corruption. They have thus prevented even retroactive transparency so that Argentine taxpayers might know what this debt was actually for, and so verify its legitimacy. One classic example of odious debt is debt incurred by a military junta to buy weapons to subjugate their country’s people, but in the Argentine case there were also costs associated with the Falkland/Malvinas war.

In preparation for the war with the UK, the junta bought advanced military hardware. This consisted of weaponry purchased from many nations, including French Exocet missiles, five of which were delivered before the war. A 2012 [5] investigation by Nick Dearden and Tim Jones from the UK Jubilee Debt Campaign analysed Argentine arms purchases bought from the UK during the bloodiest period of the Argentine Junta. Their findings indicate that:

In 1976 two “Type 42” Vickers Destroyers were bought for £40 million along with Seacat & Tigercat missiles in 1978 for £5.6 million from Short Bros Ltd (Northern Ireland) and Blowpipe Anti-Aircraft Missile Systems in 1978 for £1.5 million from the same company. Also Lynx helicopters were added to the national debt by the dictatorship in 1979 (£34 million from Westlands Ltd) with more missiles bought in the same year (22 Sea Dart Missiles, at £15 million) from British Aerospace along with various other smaller items.

Some of this military hardware was subsequently used in the 1982 Malvinas/Falklands war. The war in the South Atlantic was itself a desperate attempt to bolster support for the junta as word began to spread of human rights violations and as the Argentine economy collapsed. At first the struggle was successful in rousing Argentina nationalist fervour, but even this support for the junta collapsed in 1983 after Argentina lost the war with the UK. Though these military purchases by the illegitimate Argentine junta are clearly candidates for debt relief, since they consist of odious debt, the Argentine Government in 2014 is still unwilling to audit this odious debt.

Following the coup, the disastrous policies of Joe’s protégé Domingo Felipe Cavallo, combined with rising interest rates on dollar loans in the 1980’s, inflated Argentina’s debt above $100,000 million. Over the next few administrations, hyperinflation culminated in Argentina’s ill-fated experiment in currency stabilization. The “convertibility plan” pegged the Argentine peso to the US dollar at parity (one peso to one dollar). When Cavallo’s convertibility plan itself failed, the peso devalued in the resulting financial collapse of 2002, which yielded 34 dead protesters in the streets and four toppled presidents in just one week.

Restructuring

In 2003, when Roberto Lavagna was working at the Argentine Council on Foreign Relations in Europe, he was recalled and offered the role of Minister of Economics. He accepted the post, restructuring and renegotiating the debt, but refrained from requesting an audit. Lavagna’s bond exchange plan eventually achieved over 92% acceptance, leaving just 7.8% of the bondholders as holdouts, so called because they held out not accepting Lavagna’s debt restructuring offer. This minority was not forced to accept the majority decision due to a lack of collective action clauses (CACs) in the bond contracts. Instead subsequent governments chose to continue repayment in full of all of Lavagna’s renegotiated debt without paying anything to the vulture funds. These days failing to reach an agreement with holdouts seems to be intolerable government resistance to the private debt markets, hence the lawsuit.

Griesa’s decision was to block payments to the 92% of bondholders was intended as a mechanism to force payment in full to the remaining 7.8% of holdouts. Griesa’s decision has now led to a second default of the restructured bonds as payments have been impeded by this decision.

What’s Next?

Despite their legal victory in New York, the vulture funds have played the default card and lost because they have not been paid. The Argentine government is willing to pay them, but not in the amounts they demand. Voices in the street clamour for no payment at all.

On Monday September 29, 2014, Judge Griesa ruled following a quick hearing that Argentina is now in contempt of his court in the New York Southern District, adding that he would determine sanctions later. The vultures have asked for $50,000 per day. Griesa noted that Argentina’s attempt to bypass the hold placed by his ruling on payments to the 92% at the Bank of New York Mellon was a “very concrete proposal that would clearly violate the injunction.” The reaction in Buenos Aires was fierce indignation on the part of President Christina Fernández de Kirchner who faces waning popularity and an election in 2015. The Argentine Ambassador described the decision as a “legal absurdity.”

The government has since turned inside its shores and deposited funds at the Argentine bank Nación Fideicomisos. It intends to make debt payments on their sovereign debt to the 92% of creditors who agreed to the restructuring, thus keeping these creditors and the Club of Paris happy. Political voices on the left (and some on the right) are calling for a debt audit, they do not want to pay the vultures anything. The government has considered offering the vultures what the other 92% of bond-holders received, but the vultures have rejected that offer, one that might be considered quite generous at this stage. The vultures continue to do what vultures do, insisting on a full payment plus defaulted back interest payments.

Joseph Stiglitz has called for the UN to intervene[6], and his calls have not fallen on deaf ears. US private bankers and other stakeholders have called for legal changes in future bond debt contracts to prevent this kind of situation from happening again. The proposal[7] entails a market approach without public participation at the national or UN level, not even for public (sovereign) debt. Their proposal is simply to add compulsory CAC clauses to future bond contracts so that holdouts are forced to accept restructuring agreements which 75% or more of creditors accept.

The Argentine government cannot afford to pay the holdouts now, at least not until the end of the year when “Rights Upon Future Offers” (RUFO) clauses expire. The stalemate, litigation and political positioning continue. The US government will probably not acquiesce to ICC jurisdiction, or will politely ignore the Argentine request. The UN decision is important, it might even be considered a landmark decision, but on a practical basis it is as yet unregulated and non-binding. It is, however, a hopeful beginning. Predictably most of the states with lending investors (mainly banks and funds) —–including the US—voted against the measure, but Latin America States voted for the measure with the exception of Mexico. The Argentine legislative attempt to control the jurisdiction over Argentine sovereign bonds is a sensible one but fraught with legal complications.

The US government could solve the Griesa problem internally, noting the amicus briefs filed by the Argentine government and the Banking Association of America in the Supreme Court case not granted certiorari, but it has as yet chosen to do nothing. Despite the unprecedented litigation, the US government could intervene to unplug the stopped interest payments and end the default, and so avoid possible damage to lucrative Wall Street banking business by protecting the hundred of billions in sovereign debt repayments passing through US banks in US dollars every month. It may be relevant to understand US government inaction that Paul Elliott Singer[4], has great political clout in the country. Mr. Singer is the founder and CEO of the vulture fund called NML Capital Ltd. (an Elliott Management subsidiary), a primary litigant in the Argentine/Griesa case. Other major litigants include Kenneth Dart, once Michigan’s richest man, now a US tax exile and an Irish citizen; Dart runs the vulture fund called EM Ltd. with claims against Argentina in the litigation of over $700 million.

Stepping back from this tiny default on Argentine holdout debt to see the big picture, one has to ask: why this untoward emphasis on Argentina? Enormous debt overhangs as a mushroom cap over many first world nations such as the US, Japan and many peripheral states in Europe. Defaults on such debts pose a much bigger (and so much more dangerous) threat to the private financial bondholders. For example, how would one restructure a US default?

One interpretation of this litigation is that it may represent a late challenge to Roberto Lavagna’s Argentine restructuring of 2005. If that is the intent, then this unusually restrictive Griesa ruling could be considered a warning to other bigger indebted countries that trying to restructure sovereign debt is futile since debt speculators will attempt to scuttle such attempts in the end.

Conclusion

The Argentine junta expanded the national debt, some of which is fraudulent and some illegitimate. Subsequently, mismanagement and corruption, along with extremely high interest rates, spanned over various administrations (often with Domingo Cavallo as Economics Minister) between 1983-2002. The resultant explosion in debt caused the 2002 default, which Roberto Lavagna then restructured in 2005. This restructuring was accepted by a majority but the holdout minority began a decade-long litigation against this restructuring. Judge Griesa eventually decided in favour of the holdouts imposing a block (for non-payment in full to the vultures) which stopped payments to the majority who had accepted the restructured debt offer. This forced another technical default that brings us to the present day and the mess that Argentina now faces.

Whatever is the ultimate result of this Griesa decision, one thing is sure clear, and that is that none of this would have been possible if Joe had not chosen to issue Argentine bonds under the legal jurisdiction of the New York’s Southern District. One wonders how many more countries will choose to avoid this jurisdiction in the future if this legal anomaly is not cleaned up, and quickly.

Tony Phillips, Argentina, is an Irish ecological economist living in Buenos Aires. He writes about debt, development and the power of finance. He specializes in Ecological concerns for international finance and in Latin American regional integration (MERCOSUR/UNASUR). He is an analyst and translator with the Americas Program. Much of Tony’s work is published at ProjectAllende.org Tony’s most recent book Europe on the Brink can be found here: EuropeOnTheBrink.com .