In over two centuries of nationhood, Mexico has never seen a presidential inauguration like that of December 1, 2018. From the pre-dawn Indigenous ceremony to consecrate the bastón de mando—a wooden staff symbolizing government—that representatives of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples would later present to the new president, to the cultural festival that lasted into the night, Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador broke down pomp and circumstance and promised a new form of government. His most oft-repeated phrase: “I will not let you down.”

In over two centuries of nationhood, Mexico has never seen a presidential inauguration like that of December 1, 2018. From the pre-dawn Indigenous ceremony to consecrate the bastón de mando—a wooden staff symbolizing government—that representatives of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples would later present to the new president, to the cultural festival that lasted into the night, Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador broke down pomp and circumstance and promised a new form of government. His most oft-repeated phrase: “I will not let you down.”

Lopez Obrador began the day taking the oath of office in the Congress, as Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, president of the Congress, historic dissident politician and member of AMLO’s MORENA Party (Movement for National Regeneration), handed him the presidential banner. Former president Enrique Peña Nieto sat sour-faced and clearly uncomfortable on the congressional podium as the new president thanked him for not interfering in the elections, referring to the multiple frauds committed by Peña’s long-time ruling party, the PRI, in previous elections.

The Left has been robbed of electoral victory in Mexico twice in recent history. Once in 1988, with the candidacy of PRI dissident Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, and again in 2006 when authorities recognized conservative Felipe Calderon by half a percentage point and refused the demand for a broad recount of the vote. Manipulation, fraud, vote-buying, and media favoritism has long been the formula for gaining the presidency in Mexico’s past, particularly during the 71-year uninterrupted rule by the PRI. Inaugurations became formal acts that inspired real enthusiasm mainly among those who took power, in a system designed to transfer wealth and power to the wealthy and powerful.

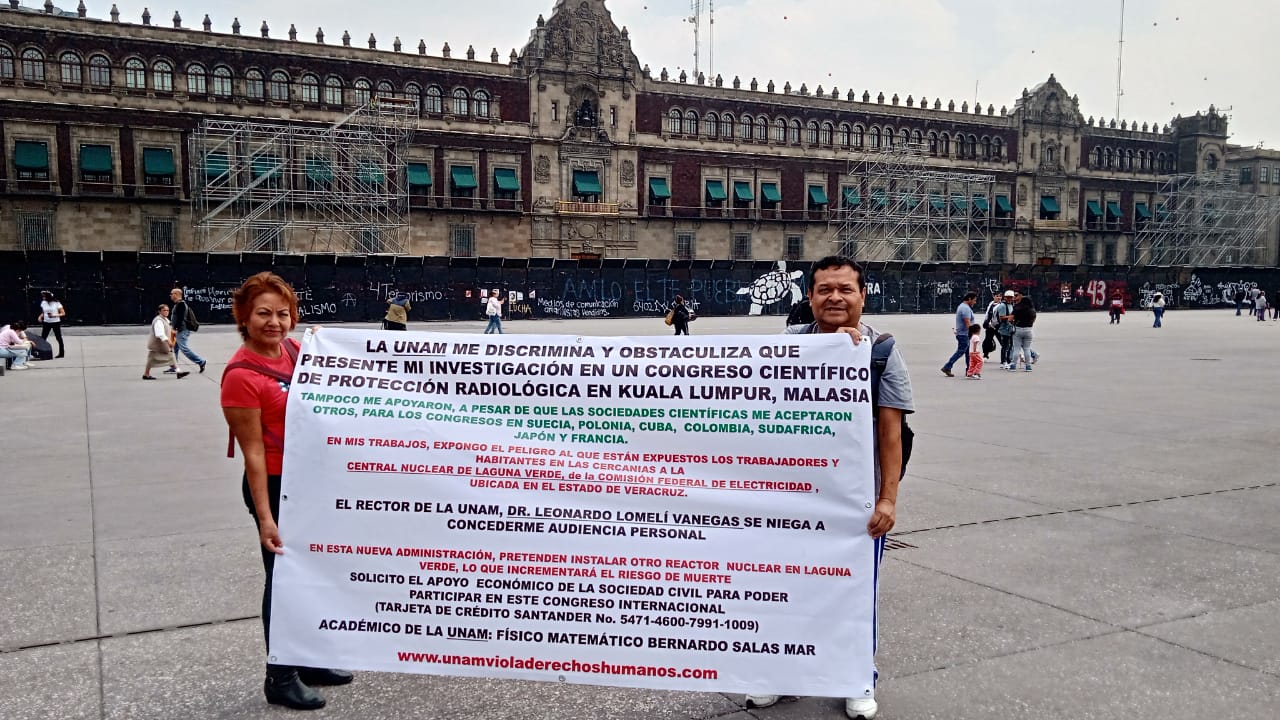

On Saturday, more than 160,000 people from across the country gathered in the city’s central plaza to watch AMLO become president of Mexico. After a ridiculously long 5-month transition period, and decades of corrupt rule, they had waited a long time. The Zocalo began to fill by morning, although AMLO would not arrive until after 5:00.

Talking to people in the Zocalo reaffirmed the astonishing change in Mexican political culture that occurred in the July 1 election. When asked what they expected, most people replied with some version of “Everything is going to change.” A woman from Iztacalco, Mexico City, said she expects increased employment under the new government. “We need jobs for everyone. With jobs, everything else works out.” She said her whole neighborhood came down early in the day “so we don’t miss anything.” There were balloons against a perfectly clear blue sky, music, cardboard masks of a beaming Lopez Obrador and a scowling Peña Nieto, often worn by side by side. The old and the new. The past and the promise.

López Obrador has done what seemed impossible in the encrusted Mexican political system: He created a sense of identification with the Mexican people. For most, voting had always been a choice between the lesser of evils, and the presidency a platform for personal enrichment, possible repression and, at best, six months of campaign followed by six years of neglect.

AMLO’s campaign and presidency dissipated the alienation towards politics among a majority of the Mexican people. The crowd chanted “¡Presidente!” “You are not alone”, and “It’s an honor to be with Obrador” frequently during the inauguration. Through the skilled crafting of messages and image, and old-style barnstorming in cities, barrios and villages where most candidates never even bothered to go, he projected a leader who listened, and humility and austerity that resonated among citizens fed up with the in-your-face opulence of the political elite in a nation where more than half the population lives below the poverty level.

López Obrador looked pleased, and reluctant to leave the stage on Saturday night. He offered a government that would represent, but even more importantly include, the people, and especially the most excluded sectors—peasant farmers, workers, Indigenous peoples. Although in this campaign López Obrador abandoned the slogan of his 2006 presidential run—“Poor People Come First”— to avoid scaring big business into attack mode, he repeated the phrase in his first presidential speech and openly denounced the neoliberal economic model.

Huge banners draped the colonial buildings that surround the pre-Hispanic ceremonial center declared the advent of the “Fourth Transformation”—AMLO’s promise to create changes on par with the three great transformations in Mexican society—Independence from Spain, the Reforms period, and the Mexican Revolution. In his speech to Congress, now controlled by his party’s coalition, the president called the Fourth Transformation a change that would be “peaceful and orderly, but at the same time profound and radical, because it will end the corruption and impunity that held back the rebirth of Mexico.”

Goodbye to Neoliberalism?

López Obrador rejected neoliberalism in stronger terms during his inauguration speech than he had during the transition period. In his speech, he lit into the capitalist neoliberal economic system, calling it a “disaster” that had failed over the past 36 years, and placing it alongside the “dishonesty of elected representatives and of the small minority that has profited of its influence” as the major causes of the nation’s woes. He railed against privatizations and promised to revert the education reform. He rejected the push for genetically modified organisms and reasserted his ban on fracking.

There are still unresolved questions about what these declarations will mean in practice. AMLO must still reckon with NAFTA, as the U.S., Mexican, and Canadian parliaments prepare to ratify an agreement that basically upholds the repudiated economic model. His administration is very aware of the leverage of international financial markets and investors, who punished Mexico for electing a leftist with a commitment to poverty alleviation by causing a temporary drop in the peso and stock market. His team will need to walk a fine line on macroeconomic policy.

Meanwhile, while environmentalists have celebrated the fracking ban, but AMLO’s ongoing commitment to oil drilling and the extractivist model in general contradicts his pledges to protect the environment. Critical moments will arise with the construction of the Maya Train in southern Mexico, the Mexico City airport expansion, and promotion of private- and public-sector megaprojects, especially in the largely peasant, Indigenous southern part of the country. AMLO has put these projects to referendum votes, a clear challenge to elite, undemocratic power structures in the country. At the same time, there are clear deficiencies in these voting processes, which have placed polling stations in areas comprising just 82% of the population, and both votes only represented 1 percent or less of the population.

Yet the symbolism and substance of his inauguration portended signs of a positive shift in the way politics are practiced in Mexico. His speech in the Zócalo emphasized 100 commitments for his administration, in which he emphasized measures to reduce waste in the government while expanding social programs. As a powerful symbol, just hours before the inauguration, the luxurious presidential mansion reopened as a public museum.

However, the100 commitments revealed a few conspicuous absences. Despite achieving close to equal representation of women in the cabinet and in congress through massive wins for candidates of his MORENA party in the recent elections, the new president did not mention women’s rights or ending violence against women. He included a vow to expand childcare, but not to defend sexual and reproductive rights. He also did not mention specifically the tens of thousands of disappeared persons in Mexico and their families who desperately search for them. Both these problems go to the root of endemic violence and inequality in Mexico. There is widespread concern that Lopez Obrador has not addressed them sufficiently and that his proposals regarding a continuation of the US-backed War on Drugs bear an alarming resemblance to those of past leaders. The Mexican population widely considers the war on drugs a failure and a cause of the record homicide rates that the nation has seen since 2007. Non-governmental organizations and activists have vowed to maintain pressure on the new government to develop and implement specific programs to address these deep-seated issues.

The AMLO administration faces huge challenges domestically and abroad, not the least of which is how to respond to a white nationalist, anti-immigrant government on its border, led by an erratic and autocratic president. AMLO greeted Mike Pence and Ivanka Trump cordially at the inauguration, as he did Miguel Diaz-Canel of Cuba, Evo Morales of Bolivia, and Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela.

Among the first acts of the new government was the signing of an “Integral Development Plan” with the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, many of whose citizens have joined the continued exodus through Mexico toward the United States. Although few details are known, the agreement includes development measures for the three countries to reduce forced migration. The leaders signed the pact without the U.S. government—a departure from the Washington-led initiatives that in part have caused the exodus.

There seems to be a recognition that the best strategy Mexico can have for healthy U.S.-Mexican relations is to stand on its own two feet. Instead of confronting the United States, the new government aims to reduce dependency by building relations around the world, developing transparent diplomacy, and consolidating democracy within.

In that endeavor, it will have plenty of allies in the international community. Mexico is well-positioned to become an example for upholding the human rights conventions and international laws that the Trump administration has vowed to dismantle.