I. “Independence” Aqueduct Threatens to Increase Yaqui Dependence

(Photo: Kenya Cuén, COBACH, Quetchehueca)

By Karim Oswaldo Duarte Nafarrate, María Marcela Rascón González,

and Reyna Selina Valenzuela Rendón

According to tribal leaders, the economic, ecological, and social stability of the Yaqui tribe is being threatened by the construction of the Sonora Sí (Sonora Yes!) project that is being imposed within its territory with the backing of the state government.

“The aqueduct is an unfair, illegal project, supported by the federal government,” says Juan Piña, Yaqui tribal governor, expressing his concern about the situation in the country and especially in the state of Sonora.

He is referring to the Acueducto Independencia (Independence Aqueduct), the largest engineering project in state history. The pipeline, under construction to bring water from the Río Yaqui to Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora, is the central part of state governor Guillermo Padrés Elias’ six-year project, called Sonora Sí.

Even as tribal governor Piña spoke out against the aqueduct, the physical work advanced eight percent in April 2012, and Gov. Padrés Elias in turn said, “The Acueducto Independencia is a fact.”

“When the work is done, water will flow at 634 gallons per second through 81 miles of pipeline between El Novillo Dam and Hermosillo,” said Padrés.

“I see it as an emblematic project, historic for Sonora, and now moving forward, without any doubt, very important for the development and growth of Sonora, for the capital, not just of the municipality, but for Sonora,” he said.

However, engineer Tomás Rojo, coordinator of the Yaqui Defense Brigade, says the purpose of the Sonora Sí project is not only to serve the interests of Gov. Padrés and President Felipe Calderón, but also of economic interests in other countries.

“As long as there is a scarcity of water in the Yaqui Valley, foreigners will have the opportunity to export their products to Mexico,” he said, referring to the fact that the valley is one of the country’s main agricultural areas.

Given that Yaqui tribal members have first rights to the water from the Yaqui River, the tribal authority has filed for legal protection, and so in reality, the aqueduct is far from being “a given,” said Mario Luna, Yaqui Tribal Defense Secretary.

The Yaqui River area used to be an oasis. The lack of water today is shameful, he says. Completing the construction of the Independence Aqueduct will make the situation worse, he adds.

In previous years, the tribe tried to help the towns of Empalme and Guaymas by allowing the construction of an aqueduct to supply the needs of the populations of these communities, he recalls.

However, that construction benefited only the tourist area of San Carlos. This is one of many reasons that 98% of the Yaqui people are not willing to accept the current project that the state government wants to impose, he says.

The state governor stressed that the coordination and support of the Calderón administration, the mayor of Hermosillo, and federal representatives have helped to advance one of the key elements of the integral program Sonora Sí. By contrast, Luna states “they never sought dialog with us.”

The journalist are high school students of the state of Sonora, Óbregon 2 high school. This article was originally published in Melóncoyote: Journalism to life the Ecological conscience Citizen Bulletin on Sustainable Development in Northeastern Mexico Summer 2012, Vol.3, No. 1, www.meloncoyote.org and published with permission from Meloncoyote for the Americas Program, www.americas.org

II. Yaqui Leaders and Engineers Highlight Risks of Agricultural Chemicals and Transgenic Crops

Now more than ever there is concern among the Yaqui, a tribe never defeated by the Spanish during their conquest of Mexico, nor by anyone else since then, that their interests are being ignored.

Today, Mario Luna, Yaqui Tribal Defense Secretary states, “We feel that they don’t take us into account and they treat us like we do not exist because of our different beliefs. That’s why we would like them to listen to us.”

Luna was speaking to a group of high school students from a number of COBACH campuses in southern Sonora. He spoke Spanish in his role as interpreter for Gov. Juan Piña and the other members of the tribal council who conduct their meetings in their native language.

Because of the tribe’s views and because they feel it is important to encourage the students and respond to the concerns of both students and teachers, they decided to offer their time and space, and even allow photos, which they usually limit, Luna explained.

Responding to a question by student Gladys Cázares, Yaqui engineers present at the meeting said the improper use and application of agricultural chemicals could cause a number of health problems, including skin cancer and leukemia.

Yaqui engineer Juan Domingo Molina complained that “crop dusters fly over the community and there doesn’t seem to be any regulation of this.”

He said that in order to apply these chemicals, the wind should be less than 5 miles per hour, but that even with stronger winds they are applied.

“There have been problems with our people,” he continued. Farm workers who spray with packs on their backs “sometimes do not read the labels, do not seal the pumps well, do not wear a mask, and get chemicals directly on their skin. These are serious problems.”

Yaqui engineer Thomas Rojo pointed out the danger of water pollution: “both with rain and irrigation, pollutants “percolate” into the ground. We know that pollutants are then extracted from groundwater via two wells,” he said. Both in utero and passed through breast milk, these chemicals “may affect children. For this reason, a study needs to be done,” he says.

“Do you know of any organic pesticide?” student Amaranta Márquez asked. The best method according to experts is integrated pest management and not using chemical agents, responded Molina. To this end, he said “they are producing insect larvae that are parasites of the Saltmarsh caterpillar (Estigmene acrea).” Rojo said that the cultivation of genetically modified plants is “very dangerous” because “genetic modification results in a plant that is resistant to certain chemicals used for pest control that would otherwise adversely affect the plant.” Genetically modified crops can cause allergic reactions and can result in the accidental modification of other species. Examples of genetically modified crops are short yellow corn and, most recently, watermelons, adds Rojo.

Ed. On September 1st the Yaqui authority along with the Citizens Movement for Water consented and presented a declaration on September 1, 2012, The Yaqui Tribe denounces the corrupt government for wanting to commit the greatest community dispossession in history, stated here in part:

The state government of Guillermo Padrés and his financial backers in a move to dispossess the Yaqui tribe and their production of foods through their principal resource, water, unsuccessfully attempted an expensive campaign to stifle resistance, the unity, social character, and popularity of the Movement. The government of Padrés failed in its efforts to stigmatize the movement as an expression of individual interests and partisanship. It also failed in its desperate effort to seize properties and intimidate with threats and bullying… The Citizens Movement for Water, September 1, 2012, celebrates together with the Yaqui Tribe the civil disobedience that occurred a year ago, in addition to celebrating how federal institutions have responded against what has been attempted against the Yaqui Valle, the state of Sonora, and Mexico.

After releasing the declaration the Yaqui protested near a highway and the legal authority of the district ordering them to stop unsuccessfully.

III. Yaqui Watershed Protection Becomes Binational Concern for Sonora, Arizona

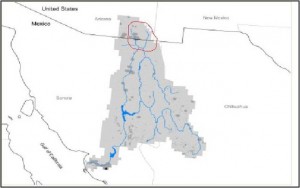

Sonora Gov. Guillermo Padres Elias’ bid to divert drinking and irrigation water from the Yaqui River Basin to industry in the state’s capital city of Hermosillo is an affront, not only to indigenous and farming communities downstream from the Novillo Dam, but also to conservationists upstream across the U.S.-Mexico border in Arizona.

Unbeknownst to the Yaqui Tribe and the Yaqui River Valley farmers, who are desperately fighting to keep the Sonora state government from appropriating the flow from their watershed, the Cuenca Los Ojos (CLO) Foundation, high in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeast Arizona, has been working feverishly for 30 years to replenish the headwaters of the Yaqui River.

“We have restored 20 percent of the original ciénaga,” CLO co-founder Valer Austin told Meloncoyote.

The Yaqui Basin is the largest river system in Sonora. The river runs approximately 320km (200mi) through the state to the Gulf of California.

Along much of the length of the binational river, no water can be seen in its sandy bed. What’s there is only enough to flow underground in the channel. Evidence of desertification is clear in the many dead trees standing and fallen along the river banks.

“The river is dry because everybody’s taking water out”, says Austin. “We’re putting water in.”

Austin’s Rancho El Coronado, not far from famed 19th Century Indian leader Geronimo’s mountain stronghold, and Rancho San Bernardino, spanning the international border near Douglas, Arizona, and Piedras Negras, Sonora, are Cuenca Los Ojos’ project sites for reviving the Rio Yaqui.

They were once ciénagas, or swamps, as indicated by the telltale dark silty talcum powder like soil. They are part of a once-vast wetland, now reduced to a fraction of its former self by poor land use practices, such as lumbering in the mountains and cattle ranching in the valleys.

“We’re trying to raise the level of stream beds so water will overflow again, spread out, and plants associated with the ciénaga will start coming back,” says Austin.

“It was dry where we are, and now there are three miles of water running through Rancho Coronado. There is water year round in the river. The land holds it like a sponge. The sponge becomes more and more beneficial for the whole Rio Yaqui system. You want to get the whole river to do that.

A century after Geronimo, CLO sent out teams to construct loose rock structures up hillsides and to shovel up earth berms with heavy machinery in order to plug erosion and capture water. This serve the purpose of slowing down the runoff from monsoon rains and catching sediment that would otherwise wash away. They built larger dam-like structures called gabions by filling wire baskets with rocks. Eventually the gabions became buried and the riverbed was raised. Now each year the gabions are being built higher. The sediment is expected to collect enough for water to spill over the surface of the terrain, re-forming the wetlands.

Austin’s concerns are for the long term and the big picture.

I’m thinking 200 years down the road” she says. “It’s systems you have to think about. For climate change, a swamp in a desert is very, very important. A swamp will hold more water than a narrow channeled river. “Trees transpiring are forming clouds. At the same time they’re holding water in the moist and shady area below their branches,” she says.

“What if we could take this system and use it on the Rio Yaqui and everywhere in the whole world?” she says.

With that in mind, she is forging links, which now encircle 25 organizations in the Yaqui-Gila Watershed Alliance. Their objective is to protect migratory routes for animals and birds that travel between Costa Rica and Canada.

Among groups involved in this crossborder initiative are the Animas Foundation, the Malpai Borderlands Group, The Nature Conservancy, Sky Islands Alliance, Wildlands, Naturalia, Pronatura, and the Northern Jaguar Project. On the part of the governments, Mexico’s National Protected Natural Areas Commission and its National Forestry Commission are involved, as well as a number of U.S. Interior Department agencies.

SUCCESS BY THE NUMBERS

Cuenca Los Ojos and adjacent ejidos are responsible for the following accomplishments:

- 500+ berms and 30,000 rock walls have been constructed.

- 54 large wire gabions have been installed.

- 12,500 acres have undergone restoration treatments.

- 4,327 acres of shrub have been treated with an aerator.

- 6,446 acres have been seeded.

- More than 700 trees have been planted every year for the last five years, along stream banks.

- Riparian acres have increased by 1,920 acres.

- As of 2011, there are five miles of perennial water in a river that was dry three years before.

- 450 students from local schools have participated in ecology field trips to study restoration work

The authors of Parts I & II are high school students at the Cobach Plantel Óbregon School 3, and Part III the co-director of Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness. These articles were originally published by Melóncoyote: Grassroots Bulletin on Sustainable Development in Northwast Mexico, Summer 2012, Vol. 3. No. 1 http://www.meloncoyote.org/issue_v3_n1/page01.html, and are published here with permission from Meloncoyote by the Americas Program, www.americas.org . This article was updated Oct. 26, 2012