While media attention was focused elsewhere, President Barack Obama made an important though low-keyed shift in rhetoric and policy toward Latin America last week. One of the Cuban Five, Rene Gonzalez, was returned home from Florida, where he was kept on probation after serving 13 years in prison. Obama’s decision, criticized as too little, too late by American supporters of Cuba, may be a step toward further diplomatic action for the rest of the Cuban Five and Alan Gross, an American AID-funded contractor held in Cuba since 2009 for smuggling illegal communications equipment.

Immediately after the U.S. gesture, Cuba issued a statement expressing its willingness to discuss the Gross case, but only in the context of humanitarian consideration towards the remaining four Cuban prisoners held in the US: Fernando Gonzalez, Antonio Guerrero, Gerardo Hernandez, and Ramon Labanino. Under an Obama executive clemency order, their terms could be reduced. Or their prison conditions can be improved, family visits facilitated, and the like. One of the men, Gerardo Hernandez, is held under hazardous maximum-security restrictions at a remote facility in Victorville, California. The prison is subject to sudden shutdowns, even when Hernandez’ lawyers travel across the country to confer with him.

Both the Cuban 5 and Gross cases are factors complicating progress toward normalization.

In an action that may be related, the FBI last week placed Assata Shakur on its “most wanted” list for her alleged role in a 1973 lethal shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike, in which one state trooper and one Panther were killed. Two others, including Shakur, were badly wounded in the incident. Convicted of murder in 1977, Shakur escaped a high-security prison in 1979 and took refuge in Cuba in 1984. The FBI “most wanted” listing of Shakur took place just as the Justice Department issued a preliminary signal that it would refuse to take Cuba off the US terrorism listing, despite thousands of petitions recently submitted to the US government last week. Cuba’s giving sanctuary to Shakur for violent events going back to 1973 may have been a US attempt to bolster its case that Cuba is a terrorist haven – a claim rejected by virtually every country in the world.

“If the decision on Rene (Gonzales) is the first of similar gestures by both sides, albeit with no apparent link, then great,” said Jose Pertierra, a Washington attorney associated with the Cuban 5 defense. “But if it’s a straight up quid pro quo…what would Cuba get for releasing Alan Gross? Rene was already out of jail and had only a year to go on his probation in South Florida,” while Gross has several years to serve.

Agreeing with Pertierra, longtime Cuba expert Saul Landau said, “Cuba needs to get something more substantial.”

The Obama gesture on Cuba also must be seen in the context of his underreported visit to Mexico and Costa Rica last week, where he met with leaders of several Central American countries. While details of the meetings are under wraps, Obama’s rhetoric marked a sharp departure from the hardline Drug War emphasis of the past decade. At least 60,000 Mexicans have been killed and thousands more disappeared in the war launched in 2006 under Mexico’s then President Felipe Calderon with full support by the Bush administration’s drug enforcement operatives and the CIA.

Opposition to the US role in the Drug War has risen sharply in Mexico and Central America, even among US allies. At the 2012 Summit of the Americas, Obama was met with open criticism over both his Drug War and Cuba policies by the region’s leaders. Stung by the attacks, Obama replaced his national security adviser for Latin America.

On the eve of the president’s trip to Mexico, hardline US counter-narcotics officials were fretting about a possible de-escalation under Obama, and the bilateral meetings appear to have confirmed their fears. In several public statements, Obama declared that economic development was a higher priority than the militarized counter-narcotics campaign. Speaking with the president of Costa Rica, Obama said, “problems like narco-trafficking arise in part when a country is vulnerable because of poverty, because of institutions that are not working for the people, and because young people don’t see a brighter future ahead.”

Acknowledging an imperial history, the New York Times reported from Costa Rica that “putting Mexico in the driver’s seat marks a shift in the balance of power that has always tipped to the United States and analysts said, will carry political risk as Congress negotiates an immigrant reform bill that is expected to include provisions for tighter border security.”

As a measure of the xenophobia that awaits Obama in the House of Representatives, the Republican chair of the Homeland Security Committee, Rep. Michael McPhaul of Texas, is warning publicly about the threat of drug cartels forming alliances with terrorist groups, a familiar drumbeat since the beginning of the Bush Administration and Mexico’s bloody drug war.

Some critics on the left, echoing the arguments for “humanitarian intervention” argue that if Obama retreats from the front lines of the militarized Drug War out of deference to Mexican sovereignty, he may fail to address massive human rights violations committed in Mexico under US military and police training.

For now, however, hawk talk is being toned down dramatically in response to Latin American pressure and grisly evidence of the Drug War’s failures. As for Cuba, Obama will have to move toward better relations over the fierce opposition of Cuba Lobby hard-liners, like Miami Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

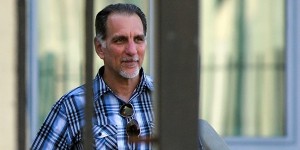

Tom Hayden is founder and Director of the Peace and Justice Resource Center in Culver City, CA. He has over fifty years of activism, politics and writing and continues to be a leading voice for peace, economic justice, saving the environment and reforming politics through a more participatory democracy.