Juan stopped in Tapachula, Chiapas to rest for a few days and to receive a routine medical check-up before heading out on the treacherous 1,700-mile long journey to Mexico’s northern border. Since he was already sitting in the Doctor’s office, he figured he might as well get one of the free quick tests offered by the Belen migrant shelter on Monday and Thursday afternoons. In under a minute, the test confirmed his worst fears: he was HIV-positive.

Juan stopped in Tapachula, Chiapas to rest for a few days and to receive a routine medical check-up before heading out on the treacherous 1,700-mile long journey to Mexico’s northern border. Since he was already sitting in the Doctor’s office, he figured he might as well get one of the free quick tests offered by the Belen migrant shelter on Monday and Thursday afternoons. In under a minute, the test confirmed his worst fears: he was HIV-positive.

It wasn’t the first time he’d received the diagnosis. Before being deported back to Honduras the previous year, he had been tested while in U.S. custody at a detention center in Texas. Convinced that Immigration and Customs Enforcement was using a scare tactic to justify his deportation, he didn’t believe the results. He also hadn’t told his wife, who sat outside the doctor’s office with their two kids waiting to receive medical care. Ten minutes later, she knew his status as well as her own.

Health at the Margins

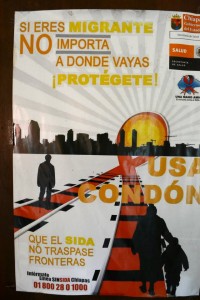

Since 2007, HIV and AIDS rates have gone up throughout rural Mexican states, partly as a result of returning migrants who have engaged in high-risk behaviors in the United States and not been able to receive diagnosis or treatment. Medical experts are shifting their attention to the particular dangers faced by Central American migrants—human trafficking, sexual abuse, prostitution, isolation, depression, and drug use—as vectors driving these numbers, especially in the southernmost state of Chiapas, where 40,000 to 60,000 migrants cross through in the hope of finding a better life in Mexico or the United States.

According to the most recent report by the National Center for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS (CENSIDA), Chiapas is the sixth state for highest accumulated AIDS cases with a registered 6,717 individuals living with the. Within the state, Tuxtla Guttierrez, Tonalá, Cintalapa and Tapachula were labeled “red flags” (Focos Rojos’)— municipalities where rates of infection and the presence of at-risk groups, like sex workers and increasingly migrants, are statistically higher than the rest of the state. Tapachula, where an estimated 95% of transiting migrants pass through, registered a total of 2,045 HIV-cases and has drawn the attention of local organizations, health groups, and migrant shelters.

Led by the charismatic Rev. Florencio Maria Rigoni of the Scalabrini Order of Missionaries, the Belen migrant shelter sits a few meters away from the brackish banks of the Cahoacan River and only 20 miles away from the Mexico-Guatemala border. The shelter’s orange and electric blue walls houses one of the starting gates for a multi-actor health response seeking to stem HIV-transmission rates.

Led by the charismatic Rev. Florencio Maria Rigoni of the Scalabrini Order of Missionaries, the Belen migrant shelter sits a few meters away from the brackish banks of the Cahoacan River and only 20 miles away from the Mexico-Guatemala border. The shelter’s orange and electric blue walls houses one of the starting gates for a multi-actor health response seeking to stem HIV-transmission rates.

These efforts begin from a modest 200 square foot office, where Dr. Ramos, his wife Leni Pundt and brother Victor Ramos offer free, voluntary medical services every Monday through Saturday afternoon to the shelter’s transient inhabitants. On Monday and Thursday, Dr. Ramos, a semi-retired general practitioner with a dead-pan sense of humor and a thick head of pewter hair, gives his HIV-prevention talks in the shelter’s mess hall with the help of graphic flip-boards and Pinocchio, a varnished wooden penis sporting plastic Mickey Mouse-style gloves, baby blue clown shoes, googly eyes and a condom as a hat.

“[Girls] would see a dildo and get embarrassed and leave,” the doctor explains. “Even the boys sometimes.”

Tact and humor, he believes, are the best medicines. But combined with the story of Juan—which always draws strong reactions from the crowd— he drives home an effective point: if you want to make your American Dream a reality, protect yourself and get tested.

Mechanics of Prevention

Funded in part by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and the Mexican Institute for Public Health (INSP), these HIV-prevention activities are part of the Reproductive and Sexual Health Project (SSR). The program initiated in migrant shelters like the Belen Shelter at high-density ‘transit stations’—towns like Tapachula that experience a high presence of migrants—in 2005. The SSR’s goal is to increase access to healthcare, HIV-prevention, testing, and treatment, and human rights protections for mobile groups, including non-citizen migrants, foreign sex workers, drug users, trafficked women and children, truck drivers, and merchant sailors, as a means to stem border town infection rates. Coordinated with the consulates of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, the project is a local incarnation of the broader 2005 Mesoamerican Project on Mobile Populations and HIV/AIDS.

Under the aegis of these programs, the Belen Shelter’s medical team has worked tirelessly since Dr. Ramos took over three years ago: Between 2009 and 2012, 14,117 migrants participated in HIV-prevention talks and received testing. Only .9% received a positive diagnosis. For the three weeks I was there in June 2012, approximately 200 people got tested. No one turned up positive.

If anyone had received a positive status and elected to stay in Tapachula, medical staff would refer them to the local Ambulatory Center for the Prevention and Attention to HIV-AIDS and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections (CAPASITS, by its Spanish initials), where previous cases have been given a free Western Blot test to determine their viral load. If a viral load falls below 400, they’re logged into the System of Administration, Logistics and Vigilance of Anti-Retrovirals (SALVAR), a national database that keeps track of patients, citizen and non-citizen alike, who receive antiretroviral drugs.

“Sometimes it’s harder for a Mexican citizen to get in the system than a foreigner,” said Judith Salazar, a social worker at the Tapachula CAPASITS, one of two modules operating in the state of Chiapas. “A Mexican would need—basically it ends up being seven documents. Foreigners usually require one form of identification, like a license, and are uploaded into the system as foreigners. If they don’t have ID we have agreements with several consulates to obtain documents for this purpose. They can then be annexed to the state insurance system to receive free antiretroviral drugs.”

However, Salazar recognized that this process takes time—nearly one to two months if things move at the normal pace. The Western Blot tests are sent to labs in the capital city of Tuxtla Gutierrez. Most don’t linger for the necessary time period to fulfill their prescribed treatment regime, let alone receive their antiretroviral drugs.

“Many leave before they can ask for routes to connect with other CAPASITS so we can streamline them and track their movements. There are fears of discrimination, deportation in both men and women, so they keep moving,” said Salazar.

In Dr. Ramos’ opinion, HIV prevalence among migrants is getting worse. His plan is to one day set up a more streamlined, digital manner of identifying and treating HIV-positive migrants as they go from shelter to shelter. “We don’t know how many are not in shelters, how many get stuck in the jungle. There’s hundreds of thousands of people coming from Central and South America, Africa, even South Asia. Not all of them come through here.”

But for migrants transiting Mexico, acknowledged the doctor, streamlining healthcare services and antiretroviral drug dispensation programs is not enough. The temporary position of undocumented migrants among the shadowy intersections of government policy, corruption, and cartel violence combined with the overarching question of who should be responsible for providing them healthcare and protection obstructs his work on a daily basis.

Sexual assault, a health hazard for women migrants

Eileen, 19, and her friend Silvia, 22, had traveled from Honduras to the Guatemala-Mexico border by bus without incident. But once crossing on foot, a gang of thugs held them up at gunpoint and demanded all their money. When they refused, the men brutally raped and assaulted them. Both were about four-months pregnant when the attack happened.

“I don’t think we’ll try again. I worked as a secretary in Tegucigalpa and wanted to do better for us in the United States because it’s no good for women there,” said Silvia as she rubbed her stomach, “Now, I also have to worry if I caught [a disease].”

The young women were suffering from severe vaginal and throat infections and had been turned away from the local hospital four times due to scheduling conflicts with the resident gynecologist. Unfortunately, Dr. Ramos could not legally treat the girls to expedite their return because they were quite literally the bodies of evidence.

“I can write up a statement on how their condition might advance after I give a preliminary check-up, but they need a forensic gynecologist or legal doctor. Whatever treatment they receive needs certification from a legal authority or else their statement against the criminals won’t be valid,” said Dr. Ramos.

Reports estimate that 30% of migrant women are sexually assaulted on their way to the United States and account for 27%t of newly diagnosed cases of HIV in Chiapas. Prevention is prominently featured in Dr. Ramos’s lectures. His discussions on the subject are always punctuated with the generous distribution of condoms to male and female audience members. But what good would a condom do in cases of rape?

“My wife and I were talking about that the other day. In these cases like [the Honduran girls’], what do you do? Tell your rapist to give you a little second so he can put a condom on and not give you AIDS or whatever else?”

Stumbling Towards Universal Healthcare and Access Guarantees

Because of the efforts of medical staff like Dr. Ramos and social workers like Judith Salazar, the number of new infection rates per year has decreased—only 108 new cases of HIV were registered since 2008. Moreover, the program has drawn attention to other health problems faced by migrants and prompted greater response from general practitioners. In 2011, over 8,000 migrants were able to access free healthcare services for conditions like dehydration, gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections brought on by prolonged exposure to the elements; and broken bones, infected wounds, and severed limbs caused by train hopping. Psychic wounds are also receiving increased attention as more medical experts on the ground are calling for subsidized counseling services to treat depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental illnesses.

Yet even with the best of intentions, this public health achievement continuously stumbles over the disjuncture between migration politics, government corruption, and resource scarcity. The ordeal thetwo Honduran girls went through is often the norm for migrant women. The inability to stem sexual violence against migrant women is part of the reason why AIDS rates are on the rise and are increasingly feminized. Prevention and sanitation should not override a woman’s right to not be raped. While groups and patrols exist to guarantee the safety of migrants, law enforcement frequently engages in sex trafficking, a lucrative business raking in $1.6bn a year across Latin America and the Caribbean, only adding fuel to the epidemic fire.

Access to healthcare and medication for HIV is also problematic. Due to international standards, Mexico ranks as a middle-income country. This means that the price tag on brand-name antiretroviral drugs—currently between $7,000 and $8,000 per person—is difficult to negotiate. Since Mexico signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, it is also subject to strict patent laws that make the production of generic drugs virtually impossible.

While antiretroviral drugs are free for all who are HIV-positive, the Mexican government has to pay way more, making their distribution to historically marginalized areas, like Chiapas, a question of cost-benefit analysis. Who gets treatment first is often based on who is sickest and who will adhere to their prescribed treatment regime. Individuals living in areas with limited access to public transportation or clinics, and migrants who will most likely leave, are sometimes seen as a liability and waste of government money.

Moreover, shortages of antiretroviral drugs are not uncommon in states like Chiapas. A recent news article stated that HIV-positive patients living in Chiapas had not received antiretroviral drugs since July 2012. The article revealed that shortages were a persistent problem, reflective of the ‘lack of coordination between the Sanitary Offices and the state council had led to dozens of people going without medication.’ Moreover, Una Mano Amiga en la Lucha Contra el Sida, a community organization based in Tapachula, declared that up to 10,000 detained migrants, non-citizen sex workers and temporary farm workers, had not received any treatment whatsoever despite having the required viral load to enroll for free antiretroviral drugs therapy.

Despite an increasingly prevalent human rights discourse on the condition of transiting migrants, discrimination is very real. Often, it is two-fold in the case of Central American’s who are undocumented and perceived as pathogenic. Amended from its harsher 1974 version in 2000, the General Law for the Population stresses that illegal immigration into Mexico is punishable with up to 2 years in prison, and up to 10 years for repeat offenders. The law reserves the Mexican government the right to deport foreigners who are considered a detriment to “economic or national interests” and lack the “mental or physical health” or “the necessary funds to support themselves.” Added to this, the state of Chiapas approved a law in 2009 on the criminalization of HIV-transmission involving carriers of the disease who knowingly engage in sexual relations with another person or infect them through some other direct means.

Bi-polar at best, the media both exemplifies and shapes this ambivalence of the state towards migrants, doing more damage than laws that may or may not be effectively enforced. In 2007, Milenio ran an article that proclaimed “Migration Spreads HIV/AIDS in Mexico”, citing a “failure of adherence to treatment” and the high rates of incidence among transiting Central Americans and returning migrants as the main cause of concentrations of the disease such as in Tapachula. So while charity is doled out, dangerous stereotypes are inadvertently created that are unfortunately trumpeted by the media.

“By paying attention to the health of migrants, we become aware of the social problems through which they traverse, so often in solitude,” writes Dr. Jorge Arellano Estrada, for Migrante magazine, “We try to heal the body, to listen to it, to heal the soul, and the evils that many migrants we attend are victim to, sometimes so far from the limits of my comprehension. Yet, these are the things that motivate me to keep helping these people which society is abandoning.”

For those who don’t pay with their lives, physical, mental, and chronic illness is how many migrants traversing Mexico and living in the United States come to bear witness to a market system that sees their bodies as disposable commodities. But unlike the United States, healthcare in Mexico is not viewed as a coveted item that requires regulation. Along the Mexico-Guatemala border, AIDS-prevention initiatives are part of broader health and human rights activism that stresses a sense of national and international responsibility. However they may stumble, these organizations, advocates, and healthcare professionals are interweaving a unified response to guarantee individual safety and universal healthcare as a human right for all people regardless of their migratory status. Their attempts pose alternatives to the way that access to healthcare has come to epitomize citizenship and privilege across the globe.

For those who don’t pay with their lives, physical, mental, and chronic illness is how many migrants traversing Mexico and living in the United States come to bear witness to a market system that sees their bodies as disposable commodities. But unlike the United States, healthcare in Mexico is not viewed as a coveted item that requires regulation. Along the Mexico-Guatemala border, AIDS-prevention initiatives are part of broader health and human rights activism that stresses a sense of national and international responsibility. However they may stumble, these organizations, advocates, and healthcare professionals are interweaving a unified response to guarantee individual safety and universal healthcare as a human right for all people regardless of their migratory status. Their attempts pose alternatives to the way that access to healthcare has come to epitomize citizenship and privilege across the globe.

Alexandra McAnarney is a communications consultant and recent graduate from the University of Chicago’s Latin American Studies M.A. Program. As part of her field research, she lived at a migrant shelter along the Mexico-Guatemala border. Before studying at the University of Chicago, she worked as a Communications Coordinator at the Florida Immigrant Coalition and as an HIV/AIDS Journalist in South Florida. She writes for the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org. A native of El Salvador and former resident of Mexico City, her work focuses on migration, youth, gangs, and health and can be found at perishmotherland.tumblr.com

All names of interviewed participants except Dr. Jorge Ramos and Judith Salazar have been shortened or changed.

Text and Photos. Alexandra McAnarney

Editor: Laura Carlsen