The thick, dirty walls of the dim-lighted cell can’t block the sounds of pain and despair from the torture taking place in an unknown military base. The image contrasts with flashes of happy family gatherings in a spacious upper-middle-class household in the affluent South zone of Rio de Janeiro city in 1971. With the dichotomy set up, the 2024 Brazilian film I’m Still Here, which just won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, skillfully portrays how the Brazilian military dictatorship terrorized thousands of Brazilian lives that would never be the same again.

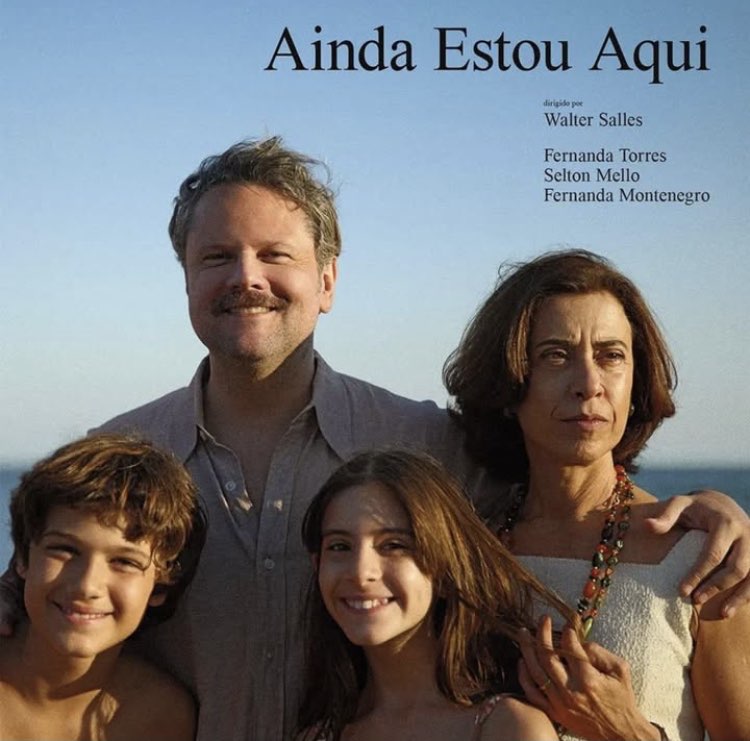

In addition to the Oscar, the acting virtuosa Fernanda Torres was awarded the Golden Globe Award for best Drama Actress, and was nominated for Best Actress in a Leading Role category at the Academy Awards.

Walter Salles’ film follows Eunice Paiva, an apolitical housewife in Rio de Janeiro, who was one of the victims. Paiva was unlawfully arrested for questioning, and endured psychological torture, sleep deprivation, and other human rights abuses for asking about the whereabouts of her husband Rubens Paiva, a former congressman who was taken from their home by state agents and never seen again.

The movie has stirred debate on the lingering pain wrought by the dictatorship in a country that is seeing the growth of historical revisionism led by far-right leaders who deny the grave abuses that took place under the dictatorship. Jair Bolsonaro once heralded a military officer convicted of torture as a “national hero”. Although Bolsonaro lost the election to President Lula da Silva in 2022, his far-right movement remains strong and his followers have aggressively criticized the film.

Debating the Dictatorship

I’m Still Here follows the real-life story of Eunice’s struggle to keep her family of five children afloat after her husband’s enforced disappearance. It portrays how she was stalked and persecuted by the oppressive regime.

The movie has been a powerful tool within the country and abroad to set the record straight and not allow the horrors of the period to become faded or distorted.

“When we shot the film, we were already aware that the fragility of democracy was something that wasn’t only pertinent to Brazil anymore. It was pertinent to too many countries in the world”, Salles told the BBC. He added that one of the first things authoritarians routinely do, he says, is “to try to erase memory and somewhat rewrite history”.

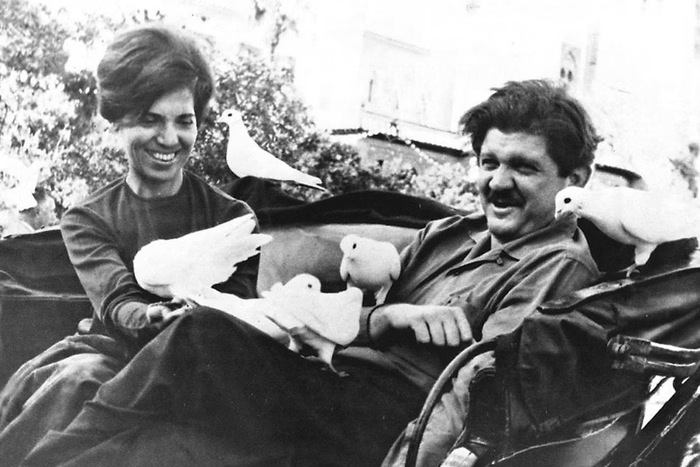

Brazilian activist Maria Amelia “Amelinha” Teles said in an interview MIRA: “The film tells with delicacy and subtleness a painful story that has left an aftermath of still-open scars, soaked in blood and tears.” Teles was a member of the communist guerrilla resistance during the dictatorship and was physically and psychologically tortured by the dictatorship.

The activist sees that: “It is a fundamental part of our unresolved history, so it touches hearts and minds. It rattles Brazilian society and other societies. The lightness in telling the story in the movie doesn’t take away from the weight of the history of the military dictatorship and how much it has been silenced.”

“As a survivor, while I was watching the picture, I felt awed at cinema’s capacity to open up such a cruel and taboo subject in Brazil to the general public, which is enforced disappearance, a crime against humanity. It invites the viewer to encounter and acknowledge, widespread state violence with seriousness, indignation and common sense, or to call it what it is, terror by an authoritarian and antidemocratic state that imposed fear, panic, and silence on Brazilian society amid so many deaths and disappearances of political activists and other Brazilians,” Teles stated.

According to the National Truth Commission, 434 people were killed or disappeared by the dictatorship. However, some experts, including public prosecutor Eugênia Augusta Gonzaga believe this number exceeds 10,000 people.

I’m Still Here has been hugely popular in its home country. It grossed $4.264 million domestically on a $1.5 million production budget, becoming Brazil’s highest-grossing film since the COVID-19 pandemic. It is being shown in foreign cinemas in Canada, the U.S. and Europe having grossed US$ 27.4 million around the world and since taking the Oscar will no doubt be catapulted into mainstream global distribution.

Katiuscia Galhera, a professor in the graduate program of sociology at the Federal University of Metropolitan Dourados (UFGD) in Brazil, sees the film as a necessary reminder for Brazil today “because it is a sensitive memory record of what we don’t want as a society.”

Galhera and Teles come from different generations, but they agree that the strength of I’m Still Here lies in how it portrays Eunice Paiva, played by Torres in her younger years and by Torres’ mother, Academy Award nominee Fernanda Montenegro (Central Station), as the older Eunice.

Teles explained: “When dealing with the disappearance of Rubens Paiva, (Eunice) kept her head high without showing despair. She endured the pain of losing her husband and the weight of surviving without the house breadwinner. In her new societal condition as a widow who didn’t even get the death certificate–a situation faced by many Brazilian families in those years–Eunice took over the social, economic, and emotional responsibilities of being a mother and a father to those children with grace, without losing her position and dignity as a middle-class wife.”

When interviewed with MIRA, Brazilian journalist and historian Lucas de Souza Martins noted that the heroine of the film was central to the development of the human rights movement in the country and the fight against oblivion.

After Rubens Paiva’s disappearance, Martins said, Paiva “refused to remain silent, becoming a vocal advocate for democracy and accountability. Unlike many political activists of the era, her fight was deeply personal—she represented the countless families who suffered without ever receiving answers. Her resilience embodies the struggle of those left behind, demanding truth in a country that preferred to move on without reckoning with its crimes.”

Eunice Paiva never formed part of guerrilla resistance or armed activity; she wasn’t even an activist. The plot is adapted from the memoir Ainda Estou Aqui (“I’m Still Here” in Portuguese) by Eunice’s son, Marcelo Rubens Paiva. It shows how many who weren’t in politics were victimized by fascist military terrorism.

“Her importance also lies in how she challenged the notion that the dictatorship only targeted armed militants,” De Souza Martins told MIRA. “By highlighting the experiences of those who weren’t part of guerrilla movements, but still faced brutal repression, her story broadens the understanding of who suffered under the regime. In a country where military apologists are downplaying the dictatorship’s impact, Eunice Paiva’s legacy is a reminder that the demand for justice isn’t about ideology, it’s about human dignity and the right to memory.”

Eunice Paiva went on to study law and became a college professor and one of the leading voices for Indigenous Rights in Brazil. She won many judicial victories in favor of victims of the military dictatorship and other forms of repression. Her life story is one of resistance that demonstrates how the dictatorship targeted women and critics.

State targeting of women

I’m Still Here gives audiences a glimpse of the apocalypse in the lives of many Brazilians during the dictatorship. With the excuse of combating communism, the military ousted elected President João Ferreira Goulart (“Jango”) from power with the aid of U.S. forces. Especially for Brazilian audiences, many of whom weren’t born yet, the film is a grim reminder of what authoritarian power looks like in real life.

The story of Eunice and her family also illustrates graphically just how hard the government hit women. Women participated in the resistance in different ways– in the student movement, political parties, unions, and clandestine groups. Many women under 30 and college students joined guerrilla forces, challenging traditional roles since war is commonly considered reserved for men. When they didn’t carry weapons, they acted as teachers or nurses among rural populations where the guerrilla operated.

Galhera pointed out that “many feminisms” flourished during that period. She highlights feminist newspapers including Brasil Mulher (Woman Brazil, 1975 – 1980) and Nós, Mulheres (We, Women, 1976 – 1978). Women defied the limits of the patriarchal roles promoted by the dictatorship: housewives, mothers and daughters. A pivotal book by Amelinha Teles and Rosalina Cruz Leite describes women’s role in grassroots movements as ranging “from literacy programs with workers, protests against poverty, and armed combat.”

“Dictatorships are misogynist, and the (Brazilian) military dictatorship acted with sexism and misogyny under the catchphrase: ‘In defense of the land and the family,’ with the purpose of keeping and deepening inequalities between men and women,” Teles stated. Women imprisoned by the dictatorship endured the most brutal forms of sexism, including rape, physical and psychological torture and often assassination. Sexual violence was a common practice when torturing these women, and their children were sometimes also physically and psychologically tortured to break their mother’s willpower.

Teles described the dominant ideology of the military regime: “They promoted the white patriarchy, reinforcing the idea that men must be the head of the family and keep it under his protection, using his authority to control women who have to be at service and disposal of the men and the family. Militant political women were considered immoral as they didn’t fit in the social role of mother and housewife. They were ‘unnatural,’ whores, bitches, and should be raped. The torturers could and should rape them, and if they got pregnant, they had to undergo a forced abortion.”

Teles added that: “Women’s rights were a forbidden subject, and contraceptives and abortion were taboo subjects. “Divorces were forbidden, and the man could force the woman to leave her job to care for the house, which would be her exclusive duty. Even requesting daycare would make them be seen as subversives,”

Operation Condor, regional repression tested in Brazil

Galhera pointed out that regression under “the Brazilian dictatorship took place when Europe was experiencing the May 68 movement, an effervescence social debates, including those regarding gender. In the US, the civil rights movement and the Black Panthers were raising awareness for equality and for human rights on basic-needs issues that deeply affected women’s lives, such as housing, education, food, and clothing.” At the same time, the U.S. government was backing antidemocratic regime changes in its “backyard”–Latin America–by supporting a far-right dictatorial regimen to oppose the so-called communist threat.

I’m Still Here has also launched a conversation about how neighboring countries dealt with Brazil’s authoritarian legacy and the role the United States played in the post-WWII South American dictatorships. The torture camp shown in the film is just one of the shadowy basements used for State-sanctioned torture in the Southern Cone. The launch of the U.S. Operation Condor in 1975 doubled down on repression.

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay coordinated Operation Condor, with collaboration and financing from the U.S. government and other international allies. Its black-ops involved intelligence operations, coups, torture and assassinations of left-wing actors in the region. It ended in 1983 with the fall of the Argentine junta.

Although I’m Still Here doesn’t mention Operation Condor, the operation and other forms of U.S. support for the dictatorship enabled the Brazilian military to carry out these vicious acts. It is estimated that Operation Condor killed between 60 to 80 thousand leftist sympathizers, with between 400 to 500 assassinated in cross-border operations, and more than 400 thousand political prisoners.

“Humanity feels the urge to know the truth, the history. It is an imperative need. What happens in Latin America reverberates around the world. There is an idea that the military dictatorship happened only in countries like Chile and Argentina and it was a ‘bland’ dictatorship in Brazil, as a major newspaper, Folha de S. Paulo wrote. The statement is far from the truth. Everybody should know that Brazil, under imperialist orders from the U.S., was the first to install a military dictatorship, the first from the South Cone, and served as a laboratory for the repression, kidnappings, tortures, rapes, and deadly disappearances. The later dictatorships in Uruguay, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina followed the same modus operandi,” said Teles.

She added, that studying history leads to the defense of freedom and democratic values besides “bringing hope and courage to keep on fighting.”

Temple University doctorate student Martins, one of the foremost Brazilian experts in US-Brazil relations, explains U.S. involvement in the 1964 Brazilian military coup that overthrew democracy.

“The US played a central role in enabling and sustaining the military dictatorships across South America, including Brazil. Washington actively supported the 1964 coup that ousted João Goulart, fearing his government was too leftist. The U.S. provided financial and military aid, trained Brazilian officers in counterinsurgency tactics, and supplied intelligence used to repress political dissidents. Declassified documents show that American officials were aware of the regime’s torture practices but chose to ignore or even justify them in the name of Cold War containment. The U.S. saw Brazil as a strategic ally in the fight against communism and was willing to overlook human rights violations to maintain its influence in the region.”

Martins went further with analysis: “In Operation Condor, the U.S. served as both a facilitator and a silent enabler of transnational repression. The CIA and other intelligence agencies helped coordinate the exchange of information between Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and other right-wing regimes to track down and eliminate leftist opponents. By supporting Brazil’s military government and turning a blind eye to its crimes, the U.S. played a crucial role in strengthening the authoritarian apparatus that ruled the country for two decades.”

After the authoritarian years, Argentina and Chile and other nations took measures to prosecute military forces and held truth commissions that led to the conviction of many responsible for state oppression. In Argentina. Military officers were tried and sentenced in what is still a precedent for historical accountability. Brazil gave amnesty to all involved, including the military responsible for torture, kidnapping, and terrorism.

Film has been crucial in highlighting citizen efforts to seek justice following the dictatorships. The Argentine experience is portrayed in the movie Argentina 1985 (2022), starring Ricardo Darín.

“Chile also confronted its past, with efforts to document human rights abuses and provide reparations to victims. These countries, despite facing resistance, made a clear decision to reckon with their authoritarian past and ensure that similar regimes would not return,” Martins pointed out.

But Brazil never really came to grips with the legacy of its 21 years of dictatorship. “The 1979 Amnesty Law effectively protected military officials from prosecution, creating a culture of impunity. While the Truth Commission established in 2011 shed light on the dictatorship’s crimes, it had no legal power to hold perpetrators accountable. The military continues to exert influence over politics, and far-right groups openly celebrate the dictatorship. Unlike its neighbors, Brazil never fully confronted its past, which is why authoritarian rhetoric and nostalgia for the regime remain dangerously present in today’s political landscape,” Martins stated.

The internationally recognized I’m Still Here invites Brazilians to reevaluate their perceptions of the military dictatorship. And foreign viewers to question authoritarian powers growing around the world today.