By Tracy L. Barnett

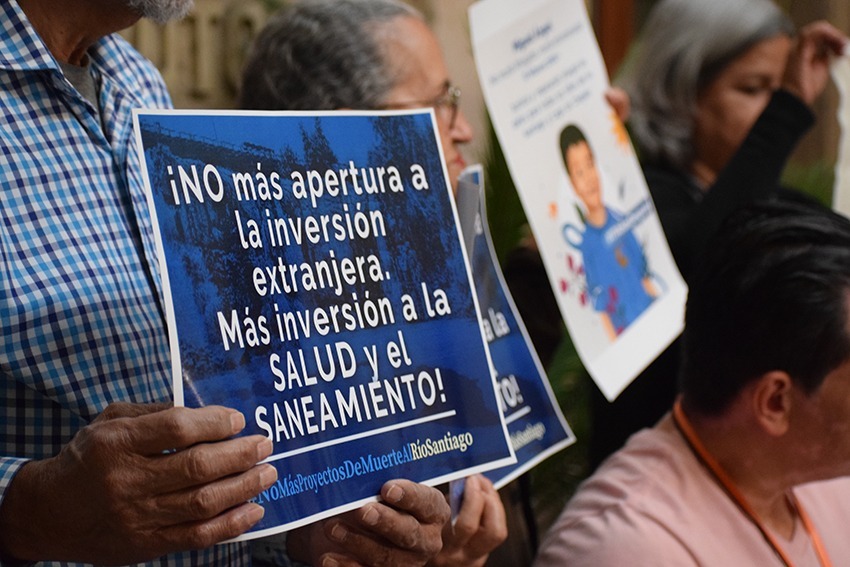

Seventeen years after 8-year-old Miguel Ángel López Rocha fell into the Santiago River and died from toxic poisoning, his death continues to fuel one of Mexico’s most determined environmental justice movements. The anniversary, marked this February 13th in El Salto, Jalisco, comes at a crucial moment as communities face both growing health impacts and new threats from industrial expansion.

“Before Miguel Ángel, our struggle seemed very ethereal,” reflects Raúl Muñoz, a resident of El Salto. “After Miguel Ángel, our cause had a name, a surname, and a face.”

The reality described by Eduardo Galeano in his book “Children of the Days” remains stark: “He didn’t die by drowning. He died by poisoning. The river contains arsenic, hydrogen sulfide, mercury, chromium, lead and furans, dumped into its waters by Aventis, Bayer, Nestlé, IBM, DuPont, Xerox, United Plastics, Celanese and other companies that are prohibited from making such ‘donations’ in their home countries.”

The El Salto Environmental Defense Citizens Committee has meticulously documented the human cost: 4,146 people have fallen ill and 2,842 have died in El Salto alone over the past 17 years. In 2024, they recorded 97 new cases of terminal chronic kidney failure and 37 new cancer cases.

Yet even as communities grapple with this health crisis, the federal government has announced plans to construct 100 new industrial parks across the country. “We’re not against development,” explains María González, a human rights defender and director of the Mexican Institute for Community Development (IMDEC), a 62-year-old nonprofit working with affected communities. “We’re against sacrifice zones.”

This tension between industrial development and community health comes to a head in the government’s new National Water Plan 2024-2030. While officials have promised 7 billion pesos for cleaning up the Lerma-Santiago watershed, community organizations warn that without fundamental changes, this could become yet another failed promise, warned Gonzalez.

“For decades, cleaning up the Santiago River has been a political banner for all parties and governments,” said González. “We’ve seen billions spent on treatment plants that don’t address root causes or hold industry accountable.”

But the movement that emerged from Miguel Ángel’s death has evolved into a sophisticated network of community organizations with clear demands and alternative visions. They’re calling for a new General Water Law that would strengthen human rights protections and community participation in decision-making. Their proposals, backed by indigenous communities, farmers, urban organizations, and academics, offer a path forward that prioritizes both development and health.

The challenge they face is substantial. The Santiago River and Lake Chapala region have become what activists call “sacrifice zones” – areas where environmental regulations go unenforced and inspection agencies have been weakened or compromised. Yet the very persistence of their movement, maintained through 17 years of documentation, organizing, and proposal-making, demonstrates the communities’ resilience and determination.

“This isn’t just about cleaning up a river,” González emphasizes. “It’s about transforming how we think about development, about who bears its costs, and about whose voices matter in making these decisions.”

As Mexico stands at a crossroads between industrial expansion and environmental protection, the communities of El Salto and Juanacatlán are showing that another way is possible – one that honors both the memory of Miguel Ángel and the future of all Mexican communities.