Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, alleged to be the head of Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, was taken into custody by US officials in New Mexico on July 25. We still don’t really know what happened. We might never know.

By Malcolm Beith

Since 2008, when the Sinaloa cartel fractured due to a rift between Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, Joaquín Guzmán Loera “El Chapo” and the Beltrán Leyva brothers, many of the second and even third-generation of Sinaloa cartel leaders have been arrested or killed. El Mayo’s brother, Jesús “El Rey” Zambada, was arrested in Mexico in 2008. His son Vicente Zambada-Niebla—a third-generation Sinaloa cartel leader—was arrested in 2009. El Chapo was captured in 2016 and sentenced in New York in 2019.

But few agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration, DEA, thought the elusive El Mayo would ever be caught. He had diabetes, it was said, and stayed in the mountains. He would never risk getting caught like those who came and went before him.

On July 25 the 76-year-old was arrested by US authorities at the International Jetport at Santa Teresa in Doña Ana County, New Mexico, along with Joaquín Guzmán López, the son of imprisoned cartel leader El Chapo. The media and social networks exploded with conjectures on how the longtime leader of the Sinaloa cartel ended up in US custody.

The first version of events claimed that El Mayo was lured to Culiacan, the Sinaloa state capital, to fly out to inspect some new property in northern Mexico and was kidnapped by Guzmán López. Then El Mayo, in a statement released to the media on Aug. 10 by his lawyer, Frank Perez, said he had gone to a ranch outside of Culiacan to meet two local politicians to resolve a dispute. It was there he met with Guzmán López, who told El Mayo to follow him, according to the statement. He went along, he said, trusting the 38-year-old who is said to be his godson.

In his statement, El Mayo claims he was then ambushed, thrown to the ground, and handcuffed by six men in military uniforms and Guzmán López. His legs were tied, and the men tied a black bag over his head. The old man, who has been on the US most-wanted list since the late 1980s, was then allegedly thrown in the back of a truck, forced onto a plane, where Guzmán López himself bound him to the seat. When they landed in New Mexico, they were both arrested. “I was kidnapped,” El Mayo declared in the letter written from prison in the US.

El Mayo said he was invited to the ranch in the northwest of Culiacan to mediate a dispute between the governor of Sinaloa, Rubén Rocha Moya, and Héctor Melesio Cuén Ojeda (a former congressman, ex-mayor of Culiacan and ex-rector of the local Autonomous University of Sinaloa) and that he expected to meet El Chapo’s older son there, Iván Archivaldo Guzmán Salazar, when Guzmán López showed up.

Who knew what, when?

In an interview, former DEA Chief of International Operations Mike Vigil, who worked in Mexico several times during his career, told me El Mayo’s claims were “nonsense.” He is unsure why El Mayo ventured out of hiding, but believes Guzmán López tricked his godfather, and made a deal with US authorities to earn a lighter sentence.

Vigil believes that the DEA didn’t know about the flight and its passengers until a few hours before it landed. Even though the DEA helped draw up the drug trafficking indictments against El Mayo, Homeland Security Investigations and FBI agents, who have taken on a more significant role in Mexico-related drug trafficking investigations in recent years, made the arrests on the tarmac in New Mexico.

Vigil also does not believe El Mayo would have agreed to meet with Iván Archivaldo in Culiacan, given that the relationship between the Zambadas and the Guzmán sons has long been severed. Rocha has denied all involvement, saying he wasn’t even in Culiacan that day, but visiting relatives in Los Angeles. A flight log leaked to the media corroborates this. Cuén was killed in Culiacan on July 25, several hours after the alleged meeting. State authorities released a video from a gas station where a victim — supposedly Cuén — is targeted for a robbery and shot once.

The Mexican Attorney General’s Office is conducting its own investigation, and cited “irregularities” in the report by the Sinaloa authorities since the autopsy revealed that Cuén took four bullets to the head. The state Attorney General then proffered her resignation.

El Mayo also weighed in: “I know that the official version given by the Sinaloa state authorities is that Héctor Cuén was shot the night of July 25 at a gas station by two men who wanted to steal his pick-up truck,” he wrote in his statement. “That’s not what happened. They killed him at the same time and in the same place where they kidnapped me.” El Mayo’s claims would suggest that top political figures are involved in the criminal underworld, or at least that they viewed El Mayo as an influential citizen with the power to resolve a dispute about who should take over the leadership role at the University. This could help portray him as a reputable pillar of the community in court, but he offers no real evidence of the alleged meeting or chain of events.

Perez, the lawyer, emphasized the abduction version in a statement in late July, stating that his client “neither surrendered nor negotiated any terms with the U.S. government. Joaquín Guzmán López forcibly kidnapped [El Mayo.]”

Doubts and Certainties

However, some of the claims made by El Mayo raise doubts similar to those raised by claims made by Sinaloa cartel witnesses in US courts in recent years. El Rey Zambada, El Mayo’s brother, famously testified that he gave former Mexican police chief Genaro García Luna millions of dollars in briefcases, an amount that physically cannot fit in a suitcase. He then changed his testimony to say he passed off the cash in gym bags.

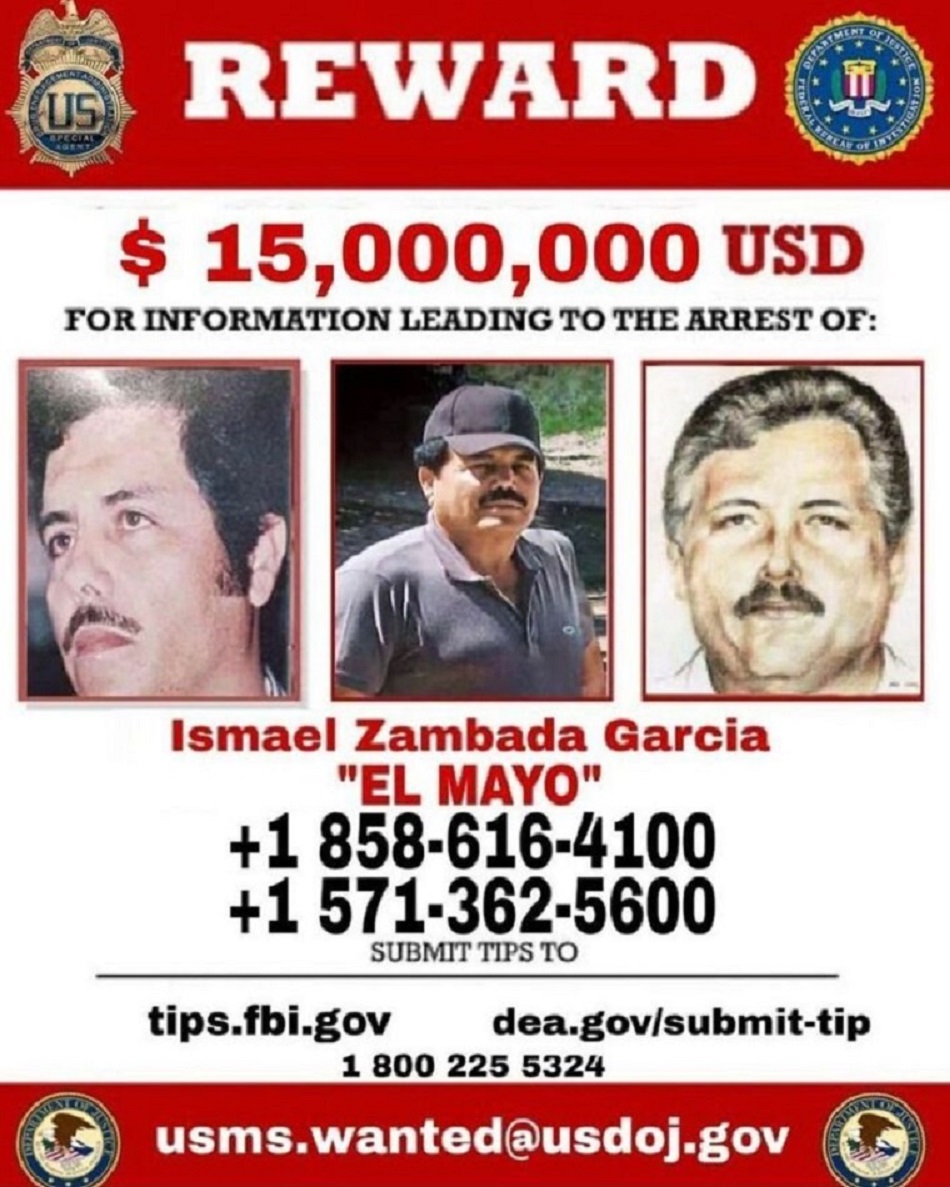

While El Mayo’s case is surrounded by speculation, no one disputes the fact that Guzmán López turned himself in to US authorities. The US had a $15 million reward out for information leading to El Mayo’s capture, but it’s likely Guzmán López brokered a separate deal. His father, El Chapo, will certainly spend life in prison in Colorado, but his brother Ovidio, who was extradited to the U.S. on Sept 15, 2023, has yet to be tried.

It’s possible that Ovidio, Joaquín and perhaps even Iván Archivaldo will try to cut deals similar to the one given to El Mayo’s son Vicente Zambada-Niebla. When he was arrested in 2009, Zambada-Niebla was already seeking to negotiate with the DEA. When he went to prison in Chicago, he began feeding the DEA information about drug shipments.

This deal with the US government was kept secret for about a year, in spite of the press being all over the case. Zambada-Niebla was eventually sentenced to 15 years instead of life in prison. Then, after testifying against El Chapo in another plea bargain in 2019, he served a few more years and was freed in 2021 and is now living under witness protection in the United States.

Since the late 00s, the Sinaloa cartel was actively trying to work the DEA in Mexico to its advantage. According to DEA agents who worked in Mexico who I interviewed for my book “The Last Narco,” there was no pact between the authorities and the Sinaloa cartel–the DEA took information without offering anything in return. “We take information from wherever we can get it,” one Mexico City-based DEA agent told me in 2009. “What, a high-level person comes to us from one organization and we’re not going to use it?’

Through intermediaries and informants, the cartel fed the DEA intelligence on its rivals, in the hope that the US agents and their Mexican allies would take out its rivals and allow the Sinaloa cartel to operate freely. When he was in prison in the late 90s, even El Chapo had tried to feed the DEA information on rivals in return for the dropping of charges against his brother, Arturo.

By 2009, with DEA and Mexican priorities shifting elsewhere — violence in Michoacán had become the No. 1 issue at that time —the Sinaloa cartel had benefitted, although there was little concrete evidence of widespread collusion between the Sinaloa cartel and US authorities. According to testimony offered up by Zambada-Niebla and other witnesses after Zambada-Niebla’s arrest and confirmed by DEA agents involved in attempted negotiations, El Mayo and El Chapo were seeking a way to get their children out of the drug trade.

The DEA refused to discuss this possibility, and Zambada-Niebla was arrested by the Mexican federal police after an ill-fated meeting in a Mexico City hotel between Zambada-Niebla, an informant, and a couple of DEA agents. In spite of claims made by some journalists, academics, politicians and even some justice officials that US and Mexican authorities weren’t trying to go after the Sinaloa cartel, the Sinaloa cartel pyramid — headed by El Mayo and El Chapo—was beginning to collapse.

The drugs, of course, continued to flow to the US and Europe, regardless of whether the organization remained intact or not or how other groups positioned themselves. A year after he was extradited on Feb. 18, 2010, Zambada-Niebla cut a deal with the US Justice Department. Zambada-Niebla was given a cell phone by the DEA to contact El Mayo, who had also been given a phone through lawyers. The two spoke, the DEA monitored the calls, and they managed to seize some shipments, but nothing substantial, according to one DEA agent involved with the process. And they could never trace the calls to locate El Mayo.

In November 2013, Mexican authorities appeared to set their sights on El Mayo. Another of El Mayo’s sons, 23-year-old Serafin Zambada, was arrested while entering Arizona. In December of that year, El Mayo’s top lieutenant – Gonzalo Inzunza Inzunza, a.k.a. “El Macho Prieto” – died after a four-hour gun battle during which Mexican gunships peppered his mansion in Puerto Peñasco with bullets. That same month, another of El Mayo’s enforcers was arrested in Amsterdam. On Feb 13, 2014, Mexican authorities launched a raid in Culiacan, arresting Jesús Enrique Sandoval Romero, a.k.a. “El 19”. Sandoval was believed to be El Mayo’s chief sicario, or hitman.

Over the following six days, Mexican authorities would arrest at least ten other mid-to-high level alleged members of the Sinaloa Cartel in Sinaloa and other northwestern states. They obtained more phone numbers, and got more information on stash houses. More of El Mayo’s inner circle — relatives and trusted men — would fall in late 2013 and early 2014.

Then they appeared to abruptly change their target from El Mayo to El Chapo. Had El Mayo betrayed his partner-turned-rival in collusion with US authorities? The authorities and press in Mexico did little to dispel such speculation, but it remained speculation. On Feb 22, 2014, Mexican authorities with DEA participation, caught El Chapo in the seaside resort of Mazatlan, Sinaloa. During El Chapo’s trial in 2019, prosecutors emphasized that the defendant was either level with El Mayo in the Sinaloa cartel hierarchy or just below him. This would allow them to keep the case against the Sinaloa cartel open after El Chapo was sentenced by arguing that the top guy still had not been arrested.

Ten years and dozens of twists, turns and treacheries later, the authorities finally caught El Mayo. Currently facing charges in five US jurisdictions, El Mayo appeared in federal court in El Paso has now been transferred for trial in in the Eastern District of New York, in Brooklyn. This is the same court that heard the high-profile cases of El Chapo and former Mexican federal Secretary of Public Security, Genaro García Luna.

Since El Mayo’s arrest, Mexican authorities have been on edge, expecting violence to erupt in Sinaloa as it did on Oct. 17, 2019, when Mexican soldiers and police surrounded Ovidio Guzmán’s house in Culiacan in an attempt to arrest him. Hundreds of cartel gunmen proceeded to attack targets around the city — military, government and civilian. Ovidio was released after eight soldiers were taken hostage. Violence once again broke out when Ovidio was arrested in early 2023. In the statement released through his lawyer, El Mayo called for “the people of Sinaloa to use restraint and maintain peace in our state. Nothing can be resolved by violence.” On Aug. 29, however, clashes between cartel gunmen and the military broke out in Culiacan and there have continued to be violent confrontations. There have been more clashes in the streets of the state capital than usual, but there were five less homicides, 45, in Culiacan in August than during the same period last year.

El Mayo pleaded “not guilty” in the district court in Brooklyn on Sept. 13. His trial will reveal more about the future of the Sinaloa cartel and what is at play in terms of US involvement in the drug war on the Mexican side of the border. El Mayo has registered a “not guilty” plea, but then so has Guzmán López, who apparently came to the US with the knowledge of authorities to work a plea bargain. It’s possible he has publicly pled not guilty, but secretly agreed to cooperate, as Zambada-Niebla did.

On Aug. 11, Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office said it had opened a criminal investigation into Guzmán López “for the possible crimes of illegal flight, illicit use of airports, immigration and customs violations, kidnapping, treason, and any other crimes that may apply.” Outgoing Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has had an openly tense relationship with the DEA. It remains to be seen what approach his successor, Claudia Scheinbaum, will take when she assumes office on Oct. 1.

The question remains: If US prosecutors kept the Sinaloa cartel investigation open after El Chapo’s trial in order to get to El Mayo, and have now captured most of the sons and top leadership, who will their next priority target be and how will this affect the binational relationship and continued violence in the country?

Malcolm Beith is a freelance journalist and author based in Arlington, Virginia. He is the author of two books about the drug war: The Last Narco: Inside the Hunt for El Chapo, the World’s Most Wanted Drug Lord, and Hasta El Ultimo Dia.