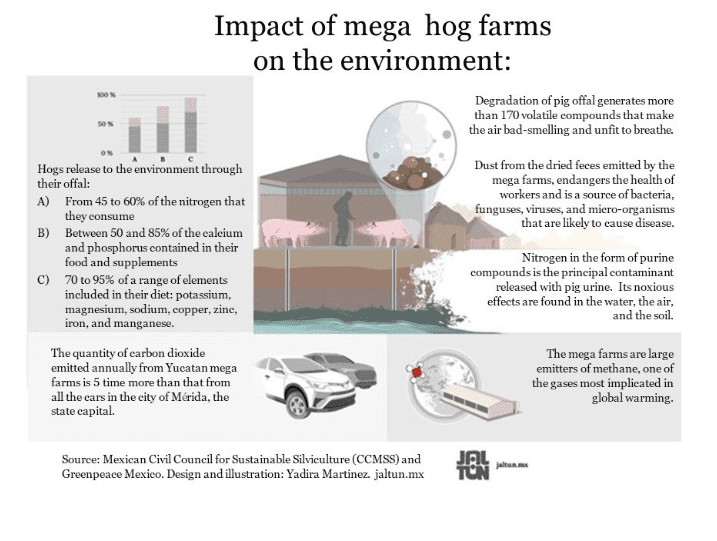

More than 220 mega hog farms operate in the Yucatan territory, wreaking havoc on water reserves, traditional agriculture, food sovereignty and territorial control by local communities. This industry relies on exports and bases its operation on the looting of natural resources, the subjugation of indigenous peoples, and a low-cost operation based on the creation of precarious employment. These accelerated and intense socio-environmental impacts have multiplied the resistance of local Mayan communities.

“The smell was what woke us up. The green flies, the mosquitoes. The headaches. The pestilence, which at night no longer lets us sleep. Then something appeared inthe fruit, as if it were smoke. The bushes looked sad and would soon dry up. Whenwe realized it, the Kekén farm had already been running for a year.

People stopped cooking outside or leaving the doors open, while the trucks full ofpigs began to pass by, day and night.

This voice and its testimony are from a member of La Esperanza de Sitilpech, a group of self-convened residents of the Sitilpech community, nestled on the edge of Izamal, the lead city of one of the Yucatecan municipalities chosen by the industry as a sacrifice zone for the business of pork export. The testimony could come as well from the Mayan communities of Kinchil, Homún, Chapab, Maxcanú or Tixpéual. All are targets for the appetite of the pork industry, while they also are of key significance for the conservation of water resources and biodiversity.

Popular mobilization in Sitilpech rejecting the reopening of the Kekén mega farm. Photo Martin Zetina

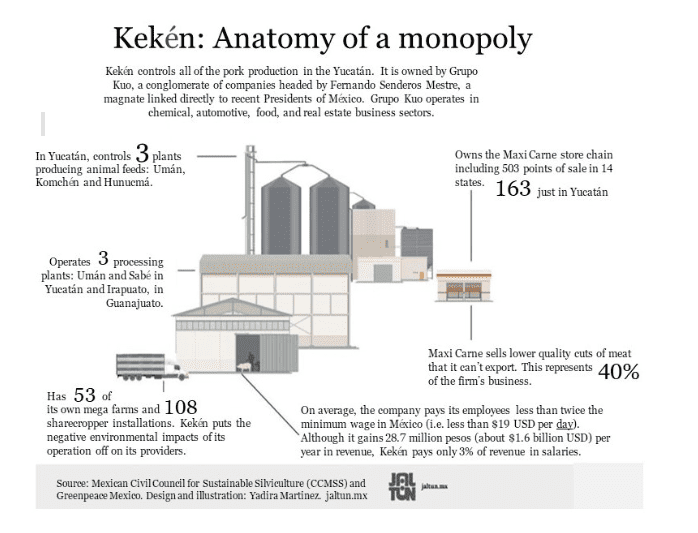

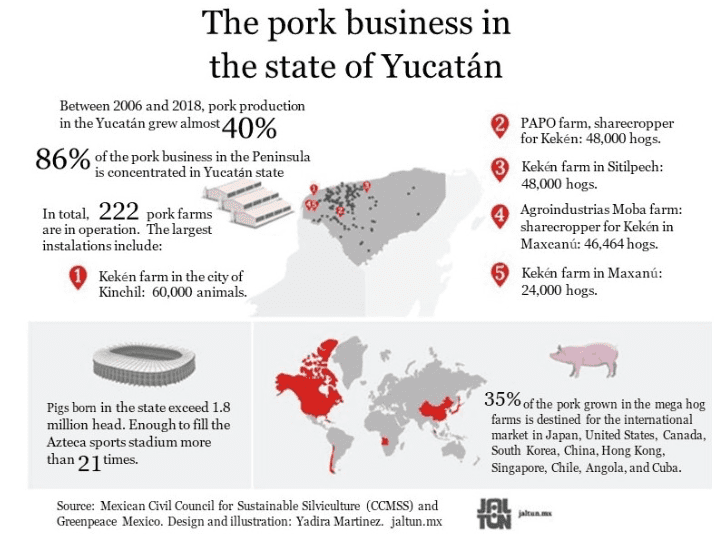

Between mega corporations and sharecropper farms that supply companies selling this meat, across the State of Yucatán there are 222 farms for raising, fattening, and slaughtering hogs. Each brings the same noxious features that threaten the survival of surrounding communities.

These industrial farms have been sited in indigenous territories without prior consultation with the inhabitants. They exploit the scarce available water and contaminate groundwater with sewage and excreta. They create a limited number of unreliable jobs, infiltrate local politics, and can break down the social fabric of the community. Through political favoritism, they operate practically without legal restriction. Taken together, this combination of factors underpins a multibillion-dollar business developed in little more than the past two decades.

A number to illustrate the latter: in the recent year and according to its report on consolidated financial statements, the Kekén firm, a true giant in the sector operating under the fiscal identity of Grupo Porcícola Mexicano, recognized annual revenues of just over 28,700 million pesos (about $1.6 billion USD).

This company, among the 20 largest pork production firms worldwide, acknowledges 53 of its own farms – including the one in Sitilpech – and 108 sharecropper facilities that supply it. Here, Kekén dispenses its environmental degradation at many facilities.

Of course, Kekén, the flagship of the powerful Kuo Group in the region, is not the only promoter of this disaster. Through its large volume and its partnership with actors of the sharecropping model, it clearly stands out in a grievance that is being multiplied across the state.

Producción Alimentaria Porcícola (PAPO), Agroindustrias Moba, GAL Porcícola, Productora Pecuaria de Yucatán and the Unión de Aparceros Chapab are some of the firms that, to a greater or lesser extent, expand the impact of an activity that grows through the power of looting and exploitation of natural and water resources. They also exploit the abundance of cheap labor in another corner of Mexico marked by high unemployment.

The highest cost of socio-environmental decline is borne by the communities where these companies settle. They pay with sickness, loss of security and food sovereignty, and also with social division between neighbors. This is the price of a production envisioned from the beginning to supply the international markets of China, South Korea, Japan, Canada and the United States.

“The farm was initiated here about four years ago. First they bought one hacienda, and we began to see the trucks with the materials. Neither the authorities nor the company held a single meeting with the people to ask us if we were for or against the farm. The municipal president (Warnel May Escobar) negotiated directly with company. The smells began to reach us as soon as the pigs multiplied”, says another resident of La Esperanza de Sitilpech.

Through these actions, the municipality of Izamal, the government of Yucatán, and Kekén’s corporate leadership all failed to comply with the requirement for free, prior, informed, and culturally adequate consultation established by Agreement 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). Non-compliance with this agreement, which was ratified by Mexico in 1990, violates the right of indigenous peoples, in this case the peninsular Mayan people, to participate effectively in decisions that affect them.

The governments also failed to comply with the Escazú Agreement, which establishes rights of access to environmental information, of public participation in decision-making processes in the territories, and also, of access to judicial defense in environmental matters. The Senate of Mexico ratified the Agreement in November 2020.

“When the farm was installed,” says one of the women from the affected communities, “they first put in 5,000 pigs. Since no one said anything, they put in another 10,000. Then 15,000. The trucks passed and passed. The bad smell came, but since the authorities are in collusion, they did not intervene”.

“They came to have up to 48,000 hogs. The farm is about 800 meters from the town. They fatten the hogs here and then move them. Every three months they do this. That was the way it was until CONAGUA (National Water Commission) finally acted and verified that the company had contaminated the water”, says one of the farmers who is part of the group.

The Kekén mega-farm in Sitilpech houses 48,000 pigs. Photo Robin Canul

Loss of autonomy and social division

The scenario of socio-environmental impact that towns like Sitilpech are going through is representative of how the evolution of the pork business on the Yucatan peninsula is built upon the subjugation of Mayan communities.

“Of the pig farms identified for the peninsula, 86% are located in Mayan-speaking indigenous territories, whose inhabitants suffer the adverse effects of contamination, impeding their right to enjoy a healthy environment,” adds a Greenpeace report released in May 2020.

At the same time, communities and local governments are victims of another effect derived from the expansion of mega hog farms: the loss of both security and food sovereignty. Due to the effects of water pollution, gas emissions and the use of pesticides within the hog farms, the crops essential to the the milpa system of agriculture are directly affected. Corn, squash, beans and others crops — the basis of food supply in the region — have suffered a perceptible and accelerated deterioration.

This further pushes communities to consume food available through the corporate commercial model, with all that this implies in terms of loss of autonomy, greater costs for families, and loss of nutritional quality.

On the other hand, the large-scale pork production system also discourages the raising of pigs at home, an activity with historical roots in a good part of Yucatán. This is due to control of the price of key inputs for raising and the fattening of these animals.

In addition, as a consequence of the well-known environmental damage caused by large-scale hog facilities, the mere presence of a limited number of pigs in a backyard –also a traditional practice in the territory– has become reason enough to ignite friction between neighbors.

In recent years, these effects led to the disappearance of pig production for home consumption. In this sense, residents of Sitilpech recognize that the pestilence and the disaster in the water generated by the mega farms also broke the practice of raising pigs at home.

The practice of growing pigs at home is nearly extinct due to the proliferation of mega farms. Photo by Robin Canul / Greenpeace.

“Now people complain if you have a pig at your house,” says another member of the group. “If I have a pig here, my neighbor will complain that she stinks. How did she do before? You had 7, 8 pigs that ran loose. Because of the farm, anyone who has pigs suffers bad publicity.”

Social friction consolidated a dependence on butcher shops that are also controlled by the owners of the mega farms. The most representative example corresponds to Maxicarne, a chain that has 163 points of sale just in Yucatan and is owned by Keken. In addition to this, local butcher shops have also become dependent on the pork monopoly.

In Yucatán, lakes formed by pig urine and excrement are growing in number. Photo Lorenzo Hernández, Robin Canul / Greenpeace

“With the farm, the flies and the green flies increased. The sour orange, the lemons are covered with something black. It doesn’t matter if you water or not. The bushes remain limp and then dry out. We started noticing that in the fields three years ago — this hadn’t happened before,” says a member of La Esperanza de Sitilpech. Next to her, a companion adds: “The fruits began to have a kind of smoke. But they are not fungus.”

“People here cooked outside their houses. Life changed with farms. Before, you had a little money but you could invest it in cookies, in a little milk. Now you have to hold onto it to buy bottled water. Before, you could drink well water and no one got sick. And it’s not even reliable water. It costs just 10 pesos a jug, so you tell me how good the filtration must be,” says the same neighbor.

Minimum jobs and popular resistance

A social tension that follows from all these changes — like the poisonous stench of the mega farm nearby – pervades the air of Sitilpech.

To a certain extent, Kekén has managed to divide a good part of the residents through tricks and misinformation. The biggest promise: the alleged creation of jobs to be generated in pork production. The group La Esperanza de Sitilpech affirms that the installation of the mega farm and its nearly 50,000 hogs barely created seven stable, direct jobs.

The accumulation of negative impacts, combined with the actions of politicians who operate as representatives of industry interests, creates a climate of mistrust. In the future, this may mute the opposition and resistance of communities that, throughout the Yucatan, suffer from the ecocide promoted by mega hog farms.

Residents and community collectives denounce political and judicial complicity. Photo Robin Canul

But the residents of Sitilpech have set themselves up as a model to imitate, both for their relentless struggle and commitment to life, as well as for the strategy that the community deployed at the judicial level.

Because of this strategy, in mid-October, Adrián Novelo Pérez, First District Judge in Yucatán, acknowledged the claims of La Esperanza de Sitilpech and upheld a protective measure that prohibited the operation of the Kekén mega farm. This, after verifying that the facilities contaminate the water.

The judge ruled that CONAGUA should continue to monitor the firm’s actions. It should assure the ongoing closure of water wells that, prior to the ruling, Kekén exploited for the operation of its plant.

The decision was obtained primarily through the resistance of the Sitilpech community. This has brought some hope and expectation to the Yucatecan populations of Chocholá and Panabá. These locations also suffer from the impacts of the pork industry and, in the last weeks of 2022, its inhabitants anticipated that they will seek legal advice to transfer the battle against mega farms to the courts.

Of course, the scenario is far from being a simple matter for the communities. At the end of December, Jorge Edén Wynter, magistrate of the collegiate tribunal court of Mérida, granted the requests of the legal representatives of Kekén and authorized the reopening of the pig facilities in Sitilpech.

In February 2023, the people of Sitilpech watched in outrage as trucks loaded with pigs drove past on their way to the nearby mega-farm. This represents the first step in the new deployment of an activity that, as shown by those who live there, has a fatal impact on the daily life of the community.

Chapab: water for the mega farm and not for the village

Located in the southern part of western Yucatán, Chapab is another of the municipalities affected by the pork industry – but with particularities that make it a sadly unique case. Five years ago, the town became another stronghold of the Kekén corporation, which through one of its sharecroppers has fattening facilities just two kilometers from the urban area.

This farm sprang up as an option after a judge ordered the total halt on the operation of other facilities that served the company in Homún. Barely 46 kilometers separate one town from the other.

Far from being discouraged after the legal setback obtained from the resistance of the Mayan communities, in 2017 the hog farm controlled by Grupo Kuo supported an initiative promoted by Producción Alimentaria Porcícola (PAPO) on a site of 65 hectares located in an ejidal (community property) area.

Behind PAPO is Grupo SIPSE, one of the most important media conglomerates in the state of Yucatan and permanent spokesperson for the interests of regional pork businessmen.

The residents of Chapab say that, from one moment to the next, and without prior consultation with the inhabitants, the ejido lands occupied by PAPO came to have a private owner, not a member of the municipality. This was businessman Jorge Antonio Zumárraga Novelo, linked directly to the sharecropper. Here is an alleged owner who the members of the community have never seen in person and barely recognize from posts disclosed through social networks such as Facebook.

It took just a year for the negative effects of the mega farm to begin impacting the daily life of Chapab. “The water began to become contaminated and most of the plants of the peasants who work near the farm dried up. There are 60 families, orange and lemon producers, who began to lose their crops,” says one of the ejido members. “Before the hog farm, the plants looked green, and now there is nothing left. The bushes are drying up from the roots and then they break”.

“Before — no more than 5 years ago — each citrus plant gave 5 or 6 crates. Now they barely give 1 or 2. Nothing comes to the poor peasants anymore.This is the fault of the farm and alsoof the authorities, who are against the peasants,” he adds. Lizbeth Rivero Zapata, current mayor of Chapab, heads the list of officials designated by the producers of oranges and lemons as collaborators with PAPO interests in that Yucatecan town.

Expansion of the mega farms compromises the survival of milpa farming. Photo Robin Canul

In 2021, CONAGUA ordered the closure of six water wells on the disputed mega farm in Chapab. Mayor Rivero Zapata’s response was to immediately enable the company to use the water from municipal supply. Since then and so far, PAPO extracts up to six tanker trucks – better known as “pipe trucks” – from Chapab’s reserves daily, with a capacity to store 30,000 to 70,000 liters per vehicle.

Of note, this guarantee lets the company draw water all day, while the community is only supplied twice a day. “The people have water between 8 and 11 in the morning, then the flow is closed until 4 in the afternoon. At 4 it reopens until 6, always in the afternoon. Then there is no more water until the next day. The farm, on the other hand, spends the night hauling water. What’s more, the company doesn’t pay for the water, while we, the neighbors, do have to pay,” says another ejido member.

In other words, the inhabitants of Chapab essentially pay for the consumption of water that by PAPO. They give up their money, moreover, for a resource that they can no longer drink, due to changes in flavor and the pestilent odor that emanates from the water. To that, add changes in local health ailments. Residents don’t hesitate to link this with the high contamination evident in their urban wells.

“Before, we drank water from the wells. Now no one does. The water: it’s yellow, it smells like pork. Now you drink only purified water. But it continues to be used to wash dishes, clothes, even to bathe. From this, many people began to have spots on their skin. It also became more common to suffer from diarrhea, vomiting or fever”, assures the same interview.

“Then there are the gases from the hogs, which reach our houses after the company ventilates at dawn. When the sump with animal feces swells from accumulated gases, the farm releases it and the town is left reeking of hogs for hours. Up to four times each morning, they open everything to get those gases out. Imagine the amount that those 48,000 hogs generate ”, he adds.

Well-worn promises of job creation proclaimed by this type of industry are also at odds with reality. PAPO barely employs 20 Chapab people. What there is certainty about is the attempts of this company and its ally Kekén to obtain public favor through welfare campaigns and handouts that are delivered periodically to certain residents.

“Kekén gives uniforms and paint to the school. Sometimes they also bring practitioners of medicine from the UADY (Autonomous University of Yucatan) that care for the families of those who are attached to the municipal palace. The company says they are doctors, but we realized that they are just students. They come, put a dome tent in the town center, and they serve 10 or 15 people. Nothing else. The practitioners even have the name of Kekén on their clothes”, comments a neighbor.

“Just now they brought some materials for some women, so they can start weaving hammocks. Pure Keken. The company donates a few kilos of meat when there is a party in the town. Or they bring little clowns when it’s Children’s Day. Meanwhile they leave us without water. The peasants lose what little they have and more pollution makes us sick”, she complains.

Women of hope

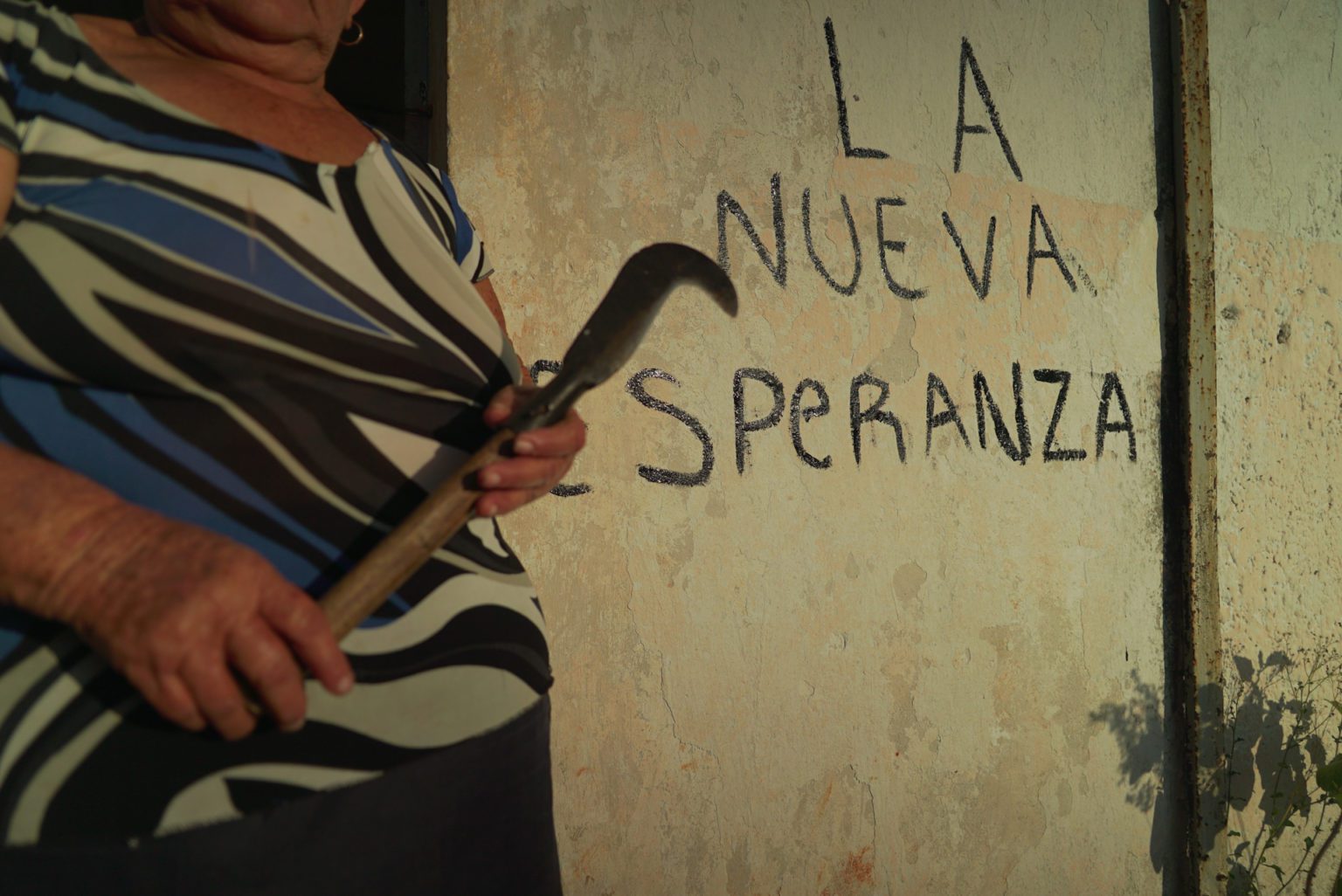

It is in Chapab itself, another territory on the pig ecocide map, where, as socio-environmental problems emerge, resistance also flourishes and multiplies. A group of women are defending the land, working in the milpa, and searching for equal rights. On a hilltop, they plant a flag that flames in hope in the midst of the injustice and impunity that permeates the pork industry and government institutions alike.

The collective bears the name La Nueva Esperanza (The New Hope) and presents itself as an updating of the previous UAIM, an acronym that refers to “Industrial Agricultural Union of Women”. On an area of two hectares, these people grow food, and they raise animals for self-consumption and for sale. Their results translate into economic autonomy and food sovereignty.

The UAIM emerged in the ejido of Chapab three decades ago with the participation of more than 40 women who, stone by stone, built a small pig farm. The desire to generate a sustainable activity was diluted with the passage of time, discouraged also by a series of bad administrations. As a result of this, the collective decided to rent the land to Kekén for a period of 13 years.

Women in Chapab restore a community farm that was under the control of Keken. Photo Robin Canul

After that period we come to the present, in which some members of the old UAIM have dedicated themselves to recovering that original idea of controlling the means of production to guarantee their own food. Currently, “The New Hope” executes his task in coordination with Kanan Lu’um Moo, a group of guardians of the land also associated with the ejido.

Along with the work of planting crops, the exchange of all kinds of knowledge between young and older women of the group is a practice that promotes day to day resilience. These productive actions lend meaning to the search for security and sovereignty in the community food base.

Balance with the ecosystem, the exchange and planting of native seeds, the use and care of drinking water, patience to wait for the recovery of the land. These are aspects that differentiate the collective from any alternative linked to agribusiness.

“We are rescuing this place, which was abandoned 13 years ago. It was 30 years ago that we initiated this goal, but it was taken away from us” says one of the women leading the recovery. “The four original representatives were there making space for other members. Now we have more than 30 members, and we want to move forward in this space to form a small ranch. We are going to put forward everything we can”, she adds excitedly.

She says that “La Nueva Esperanza” is another way to get ahead in the midst of so much dispossession promoted by mega hog farms and their corporate representatives, who know how to weigh economic power in the decisions made by the political sector that governs the municipality.

“We are rearming the group of women to get ahead. It’s 2 hectares, it’s a lot of land that we can take advantage of. Anyone who wishes, if you are willing to work with us, you can come. We want the local leaders to trust more in women. We have the right to work on this hill,” adds another member of the group.

“We plan to make a ranch out of the farm. Plant chili, cilantro, radishes, sell flowers, bananas, oranges, lime and lemon. We are going to put everything here. All the women who have an ejido in their town, they have the right to request a piece of land to work on. And this is what we are doing in La Nueva Esperanza,” she explains.

The woman speaks of what is to come, of the knowledge and experience that is shared with daughters-in-law and granddaughters. “We are going to work, we are going to sell firewood,” she anticipates.

From the initial perspective of helping the household survive, she acknowledges, her eyes are set on recovering more than just the territory. Three decades ago, she knew nothing of mega farms and exacerbated extractivism. She can recall when the water wasn’t sick and the food really was food and sprouted from the land tilled by the neighbors and not from supermarket shelves.

In that time, when the community and the forested hills still represented the best symbiosis, the challenges of a corporate economy barely loomed like a light black cloud gathering on the horizon.

Weaving resistance

Homún, Sitilpech, Chapab, Kinchil are some of the names that today lead the resistance against an economic model that disrespects the productive tradition of the Mayan peoples. This resistance is manifested in the milpa, as an expression of balanced work with the habitat, through a community spirit that understands the generation of food as an expression of being within the territory. The result is an unbreakable bond between the people and the land.

To these identities we must add two more populations that travel the path of battle to recover and redefine common spaces: Chocholá and Panabá. The trait that links these cases is in the neighborhood union, the collective as a formula for action, as a challenge to the capitalist proposal that mega farms embody, and to their owners and the support they obtain from the political structures that govern the State.

The coa, a tool that is a symbol for the women who struggle in Chapab. Photo Robin Canul

It is no coincidence that several neighborhood groups include the word “hope” in their names. Neither a coincidence that the people demonstrate in the streets and in the corporate sites where the pork industry celebrates itself. They demonstrate also in another space where these corporations believe they are untouchable: the judicial sphere.

There is no accident in the decision of the women of Chapab to reappropriate spaces in which self-procurement of food is once again honored within the sovereign genetics of the town. The remembrance of the backyard pigs of the inhabitants of Sitilpech is a longing for the autonomy that declined as the sheds of Kekén gained height.

In each town affected by the mega hog farms, for some time now the common histories began to be rewritten again. Acknowledging that the battle is at a disadvantage, and that there will be setbacks along the way. But with the confidence that brings memories marking a continuing challenge to the abuses of private capital and the historical struggle. Certain, also, that the survival of their communities is burdened by an extractivism that must be banished as soon as possible.

Text: Patricio Eleisegui – Photos: Robin Canul, Martin Zetina, Lorenzo Hernández, Cuauhtémoc Moreno and Greenpeace México – Video: Robin Canul – Voice: Rosario Nieto – Guion: Claudia Arriaga – Web design: Miguel Guzmán – Graphic design: Yadira Martínez Fernando Gonzalez – English Translation: Scott Powell.

This story was originally published in www.jaltun.mx and it’s republished here in speranza project with permission. Jaltun is a collaborative space promoted by the Mexican Civil Council for Sustainable Forestry. Jaltún, a peninsular Mayan word (from ja’: water and tuunich: stone), names a stone that, due to its natural shape, keeps water in the jungle, keeps life, giving life to other beings who drink from it.