Copyright David Bacon

During the Trump administration, the U.S. deported an average of 275,725 people per year, almost the same number of workers – 257,667 – brought by growers last year to labor in U.S. fields. Contract laborers on H2-A visas now make up is a tenth of the U.S.’s total agricultural workforce – an increase of more than 100,000 in just six years.

Deporting people while bringing in contract farm labor is not new. In 1954, during the bracero program the U.S. deported 1,074,277 people in the infamous “Operation Wetback, and brought in 309,033 contract workers. ” Two years later 445,197 braceros were brought to work on U.S. farms.

Farmworkers already living in the U.S. were replaced by contract labor when they demanded higher wages. Farmworker advocates accused the government of using deportations to create a labor shortage, and force workers and growers into the bracero program. Braceros were abused and cheated, they argued, and deported if they went on strike.

In response, civil rights and labor leaders of that era, including Cesar Chavez and Ernesto Galarza, pushed Congress to end the bracero program.

After ending the bracero program in 1964, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. A preference system for family immigration replaced the growers’ cheap labor supply scheme. By no accident, the grape strike which began the farmworkers’ union movement in Delano started the same year.

Today the Biden administration is seeking ways to undo the damage to immigrants and workers wrought by Trump’s executive orders. For farmworkers the worst of those orders came last April, when an infamous tweet suspended all the processing of family preference visas, effective ending the program won by the civil rights movement. At the same time Trump tried to cut the wages of today’s braceros, the H2-A workers, and expand the program by making it even more grower-friendly.

In one positive move, Biden rescinded Trump’s wage cut. But a deeper choice remains.

The H2-A program is even more abusive than the old bracero program. An opaque system of private recruiters and contractors brings in workers, extorting bribes for visas. Once in the U.S. these workers suffer wage theft and systematic labor violations. During the pandemic their barracks and bunk beds have become centers for spreading infection, and several have died. When workers protest conditions and go on strike they are fired and sent back to Mexico, and blacklisted for future employment.

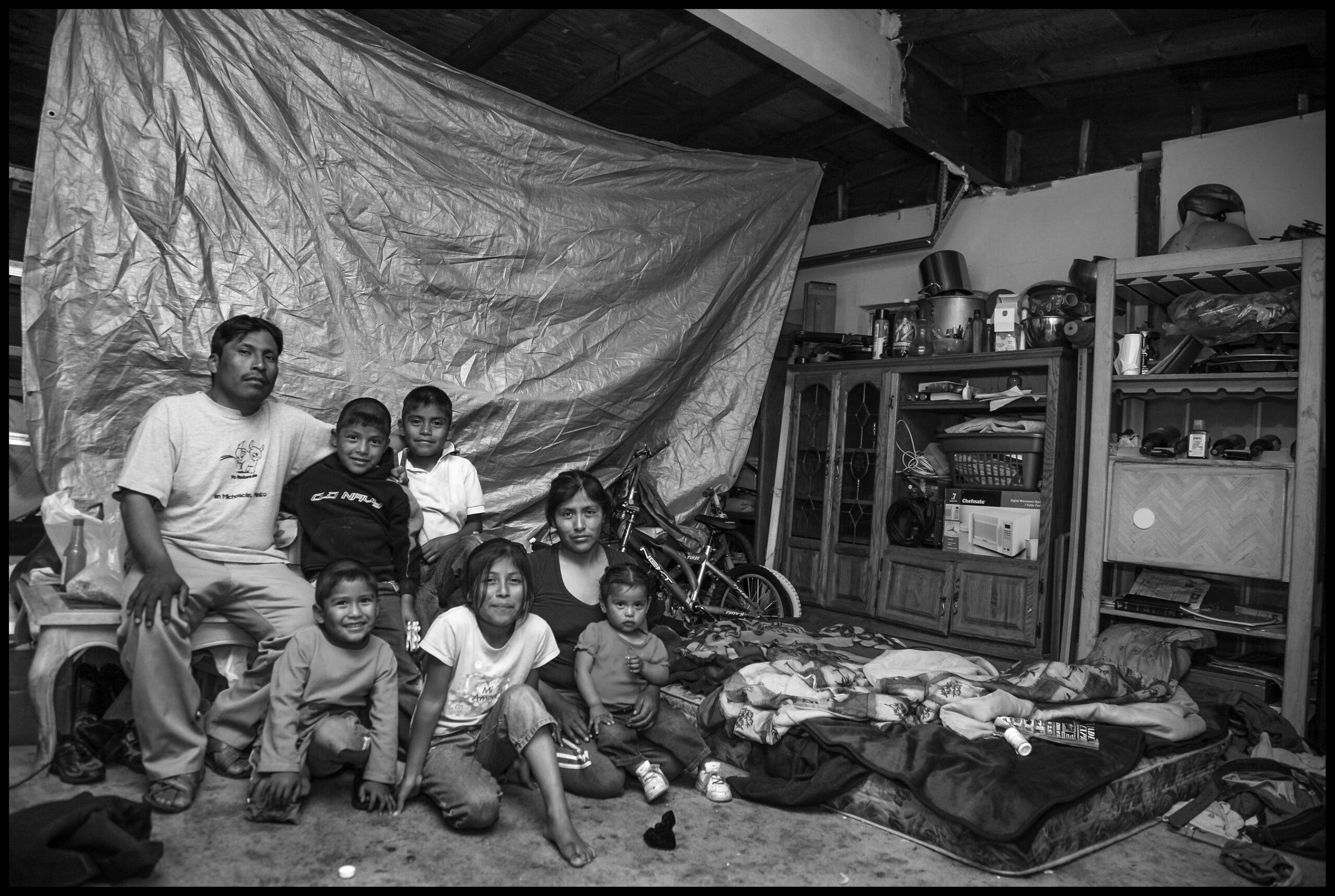

At the same time, farmworkers living in the U.S. have seen their wages stagnate. It is not unusual to see workers living in cars and under trees at harvest time. Legal cases document the replacement of resident farmworkers by H2-A workers. This is not legal, but only 26 out of over eleven thousand growers were temporarily suspended from the program last year for violations. Already in states like Georgia and Washington more than a quarter of all farm jobs are now filled by growers bringing in contract labor, and the number is rising quickly.

Over 90 percent of all farmworkers living in the U.S. are immigrants, and half are undocumented. Yet there is no way for those without papers to gain legal status. The largest agricultural employers have responded to demands for legalization with the Farm Workforce Modernization Act. It sets up the conditions for enormous growth in the H2-A program, and would likely lead to half the farm labor workforce in the U.S. laboring under H2-A visas within a few years. The bill will prohibit undocumented workers from working in agriculture, while implementing a restrictive and complex process in which some undocumented farmworkers could apply for legal status.

Instead of competing for domestic workers by raising wages, growers want H2-A workers whose wages stay only slightly above the legal minimum. This system then places workers with H-2A visas into competition with a domestic labor force, depressing the wages of all farmworkers.

For farmworkers trying to organize and change conditions, the H2-A program creates enormous obstacles. When H-2A workers themselves try to change exploitative conditions, employers can terminate their employment and end their legal visa status, in effect deporting them. Workers are then legally blacklisted, preventing their recruitment to work in future seasons. Farmworkers living in the U.S., thinking about organizing or going on strike, have to consider the risk of being replaced.

Meanwhile, farmworkers who have visas or are citizens can’t reunite their families here in the U.S. A mother who wants to bring her married daughter or son from Mexico City or Manila must wait over two decades because the family preference system has been starved for visas. Meanwhile the H2-A program grows exponentially.

Meanwhile, farmworkers who have visas or are citizens can’t reunite their families here in the U.S. A mother who wants to bring her married daughter or son from Mexico City or Manila must wait over two decades because the family preference system has been starved for visas. Meanwhile the H2-A program grows exponentially.

The time has come to do what Chavez and Galarza advocated, and won, half a century ago. The H2-A program must be ended. Family reunification visas should be made available to the families that need them. People brought by their families to the U.S. will need work, and growers can hire them and others by raising wages and bargaining with farmworker unions.

Many people in Mexico need work in the U.S. as well. Making permanent visas available that are not tied to work status, while prohibiting recruitment by employers and contractors, allows people to cross the border and settle here with families. Growers needing their labor can pay higher wages to make farm labor jobs attractive.

High-wages and secure jobs for farmworkers can only come by discarding the old deportation/guestworker model, and instead supporting families with legalization, family-based visas, and unions and labor rights.

David Bacon is a California journalist covering farm labor and immigration. His latest book is In the Fields of the North (University of California, 2017).

Anuradha Mittal is the executive director of the Oakland Institute.

This oped is based on a report on the H2-A program from the Oakland Institute, “DIGNITY OR EXPLOITATION – WHAT FUTURE FOR FARMWORKER FAMILIES IN THE UNITED STATES?”