“The instructions to donors are to bring two packages of rice, two tins of tuna, a package of sugar, a can of soup, and a package of biscuits in a transparent bag. Volunteers put orange stickers with a K for Keiko Fujimori on the bags”. This accusation of vote-buying with food donated by the upper class ladies of Lima wasn’t made by a leftist Peruvian newspaper, but rather, by Madrid’s conservative El Mundo.

The writer asserts that the campaign is using the same methods of “welfare populism” used by the ex-president Alberto Fujimori, who is serving a 25-year prison sentence for, among other things, the first degree murder of nine university students and a professor from La Cantuta in 1992 and the massacre of 15 people in Barrios Altos in 1991.

The journalist, Beatriz Jiménez, reported that “upper class women from Lima are leading a major campaign to collect supplies, blankets, and cash to be distributed in poverty-stricken areas around the capital and in rural Andean areas in the name of the Keiko Fujimori campaign”[1]. The journalist contacted the organizers and took a basket of food to see how the campaign works. The food was delivered at electoral functions before the arrival of the candidate.

The coordinator of the Mothers Clubs, Rosa Castillo, said that this has always been the style of the Fujimori campaigns: “PRONAA (the National Food Assistance Program) was a bastion of president Fujimori and distributed food for political use”[2]. Historian Nelson Manrique told El Mundo that by the end of the Fujimori government in 1999, some nine million Peruvians had been fed through help from the State and today there are a million and a half that eat in comedores populares [places where the poor can eat a good meal at a fair price].

El Mundo also reports that food is collected at the home of Jeannette Wolfenson de Stone in San Isidro, an elegant neighbourhood in the capital. Wolfenson de Stone is the sister of Moisés and Alex Wolfenson, who was convicted of fraud and the sale of the La Razón, El Chino, and El Men newspapers to Vladimiro Montesinos[3]. Her brother-in-law, James Stone, convicted of arms trafficking, was a business partner of Montesinos and owner of a group of companies that monopolized the supply of war materials during Fujimori’s administration[4].

There is much more: Nobel-prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa, a conservative liberal, wrote an opinion piece in the Madrid daily El País in which he predicts that if Keiko wins, dozens of journalists will be dismissed, and radio, television and newspapers would be converted into “propaganda machines charged with justifying all the abuses of power and slanderous and injurious coverage of critics” as happened “during the eight disgraceful years that Peru lived through” when Fujimori shut down parliament in 1992[5].

The Nobel laureate added that the archbishop of Lima, Juan Luiz Cipriani, actively supports Fujimori and kept his silence while the regime sterilized 300,000 Andean women on the orders of the dictator, among other deceptions, but is now a critic of abortion and condom-usage. He added that Fujimori supporters attack the judicial system for condemning Fujimori to 25 years in jail, that five journalists have already been fired and many more are threatened for having “humanized Humala, the other candidate”.

One of the most troubling facts that Vargas Llosa shared is that the government of Alan García, an ally of Fujimori, gave orders to the intelligence services to put Plan Sábana into action, flooding the press with slander and lies about Humala, as they did in 1990 when Vargas Llosa was a presidential candidate.

Despite it all, including that the country was governed for a decade under the authoritarian and dictatorial rule of her father, it is probable that Keiko will win the election on June 5th and become president. Why are half of Peruvians likely to vote for the Fujimoris? I believe that there are three basic reasons: the extractive economic model; the fact that Peru is a disputed territory for American hegemonic power in South America; and the fact that Peru’s poor democracy is betrayed by corrupt leadership. Let’s examine these three characteristics, in that order.

A Country Divided

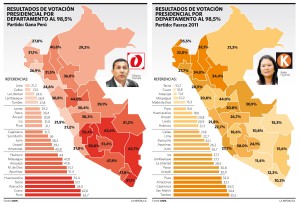

The results of the first electoral round on April 10th demonstrate that, in reality, Peru is divided: the mountains (sierra) and the jungle on one side, and the coast, especially Lima, on the other. Ollanta Humala received 31% of the vote in the country as a whole. But in the Andean region, in Puno, Cuzco, Ayacucho, Huancavelica and Apurímac, and also in the Amazonian region of Madre de Dios, he received over 50%. Nearly 50% of voters in Arequipa and Moquegua supported him; in other words, he received support throughout the south. His worst showing was in Lima, with 21.2%.

Keiko Fujimori had her best numbers in Tumbes (35.5%), on the border with Ecuador. Her results were also very good in departments in the north: San Martín, Cajamarca, Piura and Amazonas, although Humala won there. In Lima, she received 22.7%, little more than Humala. In the capital, the rightwing candidate Pedro Pablo Kucynski won, obtaining 61% in San Isidro, 57% in Miraflores and San Borja, and 50% in Surco — rich white neighborhoods in a poor mestizo country.

The only regions in which the rightwing won were Lima and Callao, garnering marginal support in the rest of the country. It received 18.5% of the votes at a national level, since Lima and Callao have about 10 million of the 30 million inhabitants of Peru. In the capital, Fujimori won in the neighborhoods with a history of popular movements such as Villa El Salvador, with 28% versus the 25% that Humala received, as well as in San Juan de Miraflores and Villa María del Triunfo. Humala won in the Lima districts of Comas, San Juan de Lurigancho and Carabayllo, demonstrating that he is capable of a strong performance in the big city.

But in the second round, the scenario completely changed. Ex-president Alejandro Toledo, who had garnered 15% in the first round, decided to support Humala despite a few hesitations. But Kuczynski, who was Minister of the Economy and president of the Council of Ministers in the government of Toledo, embarked on a strong campaign in favor of Fujimori[6]. If it was only a matter of political support, Humala would win. However, in Peru political parties are fragile structures and regional, ethnic and, especially, political culture have much more weight.

In the middle of May, opinion polls were predicting a horserace between Humala and Fujimori. One poll, commissioned by Morgan Stanley, predicted that the daughter of the dictator would win, but it appears to have been made to please its investors[7]. Vargas Llosa believes that there is a “dirty campaign and war” in Lima, that the powerful are afraid that Humala would act like Hugo Chávez, and that “in an effort to avoid socialism” they prefer “to usher in fascism. And all of this in the name of liberty, democracy and the free market!”

Again, Lima and the sierra and jungle appear on opposing sides; that is to say, Lima in opposition to the rest of the country. As has happened continuously for the last five centuries, since the Spanish made the city the principal colonial enclave in the Andean region, it is the nerve center of an age-old oligarchy that doesn’t feel Peruvian, looks to Miami, dreams in English and hates Indians and mestizos. In parallel, the sierra where Humala won handily is a region of historic land struggles where large mining companies continue to grow, contaminating the waters and carry away the riches of the country.

The Consequences of Extractivism

Journalist and writer Roger Rumrill, born in Iquitos on the banks of the Amazon River, has written 25 books on the challenges of the Amazon region, drugs and problems related to so-called “development”. In a recent article he writes, “The Amazon region is Peru’s last strategic source of income in the 21st century”. His thesis is that, after the collapse of the international banking and credit system, and with the rise of primary materials, commodities such as water, energy, biodiversity and inexpensive land have appreciated in value. All of these things exist in abundance in the Peruvian Amazon.

The enormous 700,000 square kilometers area is home to only 15% of the country’s population. But an economic system of “mercantile extractivism” dominates in the region, “based on the simple extraction of commodities, whether flora or fauna, and today gold, petroleum and gasoline are exported without processing”[8]. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th a similar process happened with rubber, which in the end left nothing in the region.

The problem with this model is that “it does not generate economic or social development because it concentrates profits in a few hands and excludes benefits for those who extract the riches of the forest and the subsoil”. For this reason, social indicators continue to worsen despite the fact that Peru has had unprecedented growth at rates of over 8% annually. In addition, the environment is being decimated to the point that mahogany, the country’s most valuable forest product, is nearing depletion.

The corruption of political power, says Rumrill, has permitted powerful business interests based in Lima to benefit from tax exemptions in order to market the products of the Amazon. The region, from which 90% of the petroleum and gas in the country is extracted and the site of one of the most productive genetic repositories on earth, today has the country’s highest levels of poverty and malnutrition.

State budgets concentrate on department capitals like Iquitos, with almost nothing left for the provinces. “In the districts of Morona and Pastaza, with an indigenous population of 99%, where the petroleum that generates the profit for the oil and gas industry is extracted, less than 2% of the budget is allotted to them”[9]. Even worse, 90% of the regional budget is spent on “public works”, like highways and buildings. “Laying cement is the order of the day”, concludes Rumrill.

The extractive model generates two opposing social sectors. On one side, a parasitic and unproductive “business class”, that appropriates nature and corrupts the State in order to facilitate access to fabulous riches. On the other side, the defenseless multitudes; there is no industry, commodities are exported unprocessed, and there is no internal market for dignified work. The Fujimoris bring the two together: they are supported by these “businessmen” and dole out aid to the poor in an effort to keep them quiet.

Peru’s Geopolitical Role

The Andean region is the stage in a geopolitical dispute between a declining superpower, the United States, and two growing powers, Brazil and China. To aid the former, it tries to put the brakes on the advance of Brazil, all the while solidifying its alliance with China. The “Pacific Alliance” (Colombia, Chile, Mexico and Peru) was born in Lima to try to revive the objectives of the extinct ALCA, based on the free trade deals that the United States has signed with all four members, although the approval of the trade deal with Colombia is still pending.

As Peruvian economist Oscar Ugarteche signals, its purpose is an alliance in opposition to Mercosur and regional integration, and more explicitly, against the Council of South American Defense, which is advancing very slowly. Washington cannot passively allow the consolidation of Mercosur and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CALC), created in February 2010 as the first agreement between all the countries in the region without the presence of the US and Canada.

One of the objectives of CALC is to design commercial mechanisms without relying on the US dollar, “in order to create a monetary, financial, and economic system in Latin America that strengthens development of needed capacities in order to integrate into the international market under conditions of equality”, according to Venezuelan Secretary of State Nicolás Maduro[10].

In addition, China has become the largest trading partner of Brazil and Chile and the second largest for Peru and Argentina[11]. That means that Pacific ports are today more important than those of the Atlantic, shifting the alignment of South American geopolitics from one ocean to another. Brazil understood this a long time ago and took the initiative to create the IIRSA (Integration of the South American Regional Infrastructure) in the year 2000.

The work of the IIRSA has been to create dozens of multimodal communication networks between the Atlantic and the Pacific, which are the master pieces in a type of integration that favors the circulation of business to and from Asia, which in turn benefits the Sao Paulo middle class. Several of these cross-oceanic corridors come together at ports in southern Peru and bring in Brazilian products from the enormous arc that spans the Amazon River basin to the port cities of south and southeast Brazil, where production is concentrated in the seventh greatest industrial power on earth.

Perhaps due to this, the Humala campaign has been supported by two prominent figures of Lula’s party, the Workers Party of Brazil (PT), Luis Favre and Vladimir Galarreta, who collaborate in designing political campaigns. In 2002 Favre was the nexus between the PT and the public relations firm of Duda Medonça, the publicists that brought Lula to triumph under the slogan of “love and peace”.

Ollanta Humala said that “Brazil needs a strategic partner on this side of the Pacific and I believe that Peru is the ideal partner for this role”[12]. The Pacific Alliance seeks to counterbalance the growing role of Brazil. It is supported by Alan García, who is suspicious of Unasur and rejects the South American Defense Council. According to journalist Dario Pignotti, if Humala wins, “Brazil will offer undeniable advantages to invest in Mercosur”[13].

Toward a True Democracy

The four children of Alberto Fujimori studied in the United States; Hiro and Keiko at Boston University, Sachi in New York, and Kenyi in Kansas. Between education, travel and accommodations, the Peruvian government paid $1,225,000 between 1992 and 2000[14]. The money was diverted from the intelligence services by Vladimiro Montesinos on the orders of the president.

This is only one small example of how the country was governed like a hacienda. Nobel laureate Vargas Llosa says that he will vote for Humala because he has signed a “Promise to the Peruvian People” in which he guarantees that he will not seek re-election, he will respect property rights, there will be no nationalizations, he will work against corruption and he will keep the public informed. The writer believes that the conditions exist to ensure he keeps his word.

His son, journalist and liberal essayist Alvaro Vargas Llosa, published “19 reasons to vote for Ollanta Humala”[15]. He maintains that, “With the Fujimoris, the moral education of the Peruvian elite, which has backward values and thinks that liberties and human rights are nothing more than foolishness, will be interrupted. The banana republic will be restored”.

He adds that with Fujimori, “mafia mercantilism” will return, “preventing the possibility that the poor regain their dignity”, “installing terror in workplaces, in newsrooms, and at tribunals”. He is certain that ‘fujimorism’ is not a model but, rather, a method: “The method of Al Capone (without the innocence)”. He also believes that her two vice-presidential candidates (Peru has two vice presidents] are a “coup-ist” and a “near-fascist”.

Of Humala, and this is very interesting, he says, “There is more guaranteed democracy. If he commits excesses, the right wing will leap on him. If the Fujimoris commit a crime or offence, the right will applaud crazily”. He also believes that Latin America has had two phenomena in the last decade, “The expansion of the middle class and the modernization of a segment of the left”. It is clear that he is thinking of the government of Lula and he gives examples of this modernization in El Salvador, Uruguay, Brazil and Chile.

He wisely reasons, “The opportunity has arisen to convert the emergency of a fascist threat into the opportunity to create an understanding between the leftwing and liberal sectors”. He concludes that “Ollanta offers the possibility to straighten out the democracy that was twisted over those ten years”.

It is interesting that well-known critics of the left have entered this discussion. They are not opportunists or upstarts; they believe in democracy and the free market. They are not enthused by Humala. But they are panicked over the prospect of the Fujimoris. And they know something about it, though many Peruvians continue to believe that they will save them either from poverty or from the poor.

Raúl Zibechi is an international analyst for Brecha of Montevideo, Uruguay, lecturer and researcher on social movements at the Multiversidad Franciscana de América Latina, and adviser to several social groups. He writes a monthly column for the Americas Program (www.americas.org).

Translated by Erin Jonasson

References

Beatriz Jiménez, “Keiko Fujimori reparte comida entre os pobres a cambio de votos”, El Mundo, in http://www.elmundo.es/america/2011/05/06/noticias/1304691775.html

Beatriz Jiménez, “Vinculan con Montesinos a la voluntaria que acopia víveres para Keiko”, in http://www.elmundo.es/america/2011/05/07/noticias/1304733529.html

Carmelo Ruiz Marrero, “El síndrome de China. La creciente presencia china en América Latina”, Programa de las Américas, April 11th, 2011. Available in English as “CHINA SYNDROME: China’s Growing Presence in Latin America”, Americas Program, April 12th, 2011 https://www.americas.org/archives/4266

Caretas (magazine): http://www.caretas.com.pe

DESCO (Centro de Estudios y Promoción del Desarrollo): http://www.desco.org.pe/

El Comercio (newspaper): http://elcomercio.pe/

La Primera (newspaper): http://www.diariolaprimeraperu.com/online/

La República (newspaper): http://www.larepublica.pe/

Oscar Ugarteche, “El bloque del Pacífico desde la integración estratégica”, ALAI, April 26th, 2011.

Quehacer (DESCO magazine): http://www.desco.org.pe/quehacer-todas.shtml?x=6808

Lucha Indígena No. 57, Cuzco, May 2011.

Mario Vargas Llosa, “La hora de la verdad”, El País, May 8th, 2011.

Rodrigo Montoya Rojas, “Segunda gran oportunidad política peruana en peligro”, Servindi, September 28th, 2010 en http://servindi.org/actualidad/32740

Roger Rumrill, “Las megainversiones en la Amazonia y sus impactos ambientales y sociales”, Servindi, May 4th, 2011, en http://servindi.org/actualidad/44295

[1] El Mundo, May 6th, 2011

[2] Ibid.

[3] El Mundo, May 7th, 2011. Montesinos was the chief of the National Intelligence Service and presidential assessor between 1990 and the year 2000. He was convicted of killings perpetrated by Colina, a paramilitary group, in La Cantuta and Barrios Altos and the disappearance and death of journalist Pedro Sauri.

[4] Ibid.

[5] El País, May 8th, 2011

[6] Kucynzski was the boss of the boss of Planning and Policy at the World Bank during the 1970s and worked for various mining companies, among others Halco Mining Inc. in Pittsburg.

[7] La Primera, May 6th, 2011

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Aporrea, April 30th, 2011

[11] Carmelo Ruiz Marrero, ob cit.

[12] Isto E magazine, April 20th, 2011

[13] Página 12, May 2nd, 2011

[14] La República, June 20th, 2010 http://www.larepublica.pe/archive/all/larepublica/20100720/9/node/279388/todos/15

[15] La Republíca, May 1st, 2011