How a pro bono organization put the brakes on a “deportation machine”

How a pro bono organization put the brakes on a “deportation machine”

Arriving in Dilley, Texas, hotels and rental trailers seem to outnumber houses. The hotels and trailer parks fill up with the workers in Dilley’s two industries: fracking and private prisons.

Dilley is home to a state prison and, since March 2015, the South Texas Family Residential Center, the largest family immigration detention center in the country. The women and children detained there have fled from Central America, South America, and as far away as Syria.

Detained immigrant families started arriving in Dilley in March 2015, and shortly after a small, driven group of lawyers and organizers known as CARA set up shop at a ranch house in town, intent on providing legal services to the detained families, and ultimately ending family detention. On a weekly basis, volunteers arriving from around the U.S. face a monumental task: provide legal representation to hundreds of women and children detained in rural Texas with no right to a lawyer.

Most of these women and children being held have never broken a law of the United States. They are being held because they are seeking asylum. “They have spent months, and all of their life savings getting to Dilley, Texas,” says CARA Managing Attorney Katie Shepard.

“Instead of providing them with the refuge we are required to do under international and domestic law, we are jailing them unnecessarily.”

The Geography of Family Detention

Dilley is half-way between San Antonio and the border at Laredo, Texas. It is a long, straight drive, with little scenery besides oil rigs and truck stops. The detention center’s design and location in Dilley is no accident.

Dilley is the third major experiment in family detention in recent years. Activists and lawyers have played direct roles in shutting down the first two, and if they succeed, Dilley will meet the same fate.

The Hutto facility in Taylor, Texas first began holding immigrant families in 2006. Hutto is run by the Corrections Corporation of America, which also runs Dilley. Austin-based lawyers and other immigration advocates succeeded in shutting down family detention at Hutto after intense campaigning.

Then in summer 2014, an increase in women and children from Central America crossing the border turned into a media crisis for President Obama. Vice President Joe Biden said that, “there is no free pass, that none of these children or women bringing children will be eligible under the existing law in the United States of America.” Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said the children “should be sent back.” The administration put the unseemly practice of family detention back into vogue.

To process the families and deport them, Homeland Security opened a family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico. The administration set the goal to deport the families within ten to fifteen days of detention, even though none of their asylum claims had been heard. Artesia is in the middle of the New Mexico desert, over three hours from El Paso, Texas, the closest city. Despite the distance, lawyers began arriving in Artesia from around the country to provide free legal services to the 500 women and children in detention.

The lawyers meticulously documented each and every case, to make sure asylum law was followed and to block illegal deportations. Within a month the pace of deportations had fallen 80%. The pro bono team also denounced the terrible conditions in the facility, where women and children alike were forced to wear jumpsuits, even though they had committed no crime, and had no phone access to contact family or lawyers. Artesia was shut down on December 15th, 2014.

In August 2014, DHS had begun sending families to Karnes, a pre-existing facility southeast of San Antonio. With Artesia closed, a new facility was constructed in Dilley, Texas and began to receive families in March 2015. Both Dilley and Karnes are over an hour south of San Antonio, in sparsely-populated rural Texas, far from lawyers and advocates who might represent the detained families.

In August 2014, DHS had begun sending families to Karnes, a pre-existing facility southeast of San Antonio. With Artesia closed, a new facility was constructed in Dilley, Texas and began to receive families in March 2015. Both Dilley and Karnes are over an hour south of San Antonio, in sparsely-populated rural Texas, far from lawyers and advocates who might represent the detained families.

“The reason they constructed this facility in Dilley is because the public was so negative about what the facility looked like in Artesia,” says CARA Project Manager Ian Philabaum. Dilley and Karnes represent a more “humane” face of family detention, with more open space, no prison jumpsuits and improved medical services. “They devised a way to make family detention look not bad,” says Philabaum.

Yet he says, “Locking up families can never be humane.”

Dilley can hold up to 2,400 people. Its current population hovers around 900. Karnes is being expanded to hold up to 800 people and at the moment over 500 people are detained there.

Locking up mothers and children

“These women are brave, they’re warriors. That’s why they have made it here,” says Ana Camila Colón, a CARA attorney, during a weekly meeting in Dilley.

The staff tick off the countries the families come from: El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Syria.

Volunteers and staff become intimately familiar with the stories of the women and children who pass through, as they help prepare the women to defend themselves in asylum interviews. The families arriving at Dilley are the face of a mass exodus from Mexico and Central America. Of the women the CARA project works with, 91% pass their Credible Fear interview, making them eligible to apply for asylum.

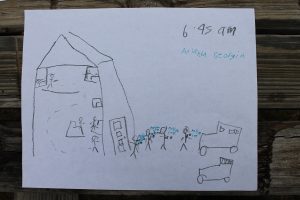

Women and children arrive at Dilley after presenting themselves on the border seeking asylum. The majority of women and children who present themselves on the border are released to live with family and ICE has never explained the process for deciding who is sent to detention. Other families at Dilley were detained after crossing undocumented into the United States and then requesting asylum. In January, families arrived who had been picked up in a wave of immigration raids, mostly near Atlanta, Georgia.

Soledad Villegas and Evelyn de León Sandoval, both from Guatemala, are sharing a room at the Casa, a shelter by San Antonio-based organization RAICES for women who have left detention. They have each been on the run for more than a month, fleeing violence.

Soledad Villegas and Evelyn de León Sandoval, both from Guatemala, are sharing a room at the Casa, a shelter by San Antonio-based organization RAICES for women who have left detention. They have each been on the run for more than a month, fleeing violence.

Villegas is a slim 25-year-old from Huehuetenango, with big eyes and long, black hair pulled back into a ponytail. Her three-year-old son sits next to her at the kitchen table, his eyes following me back and forth. He smiles shyly before burrowing his face into his mother’s chest.

She left Guatemala with her husband and son on February 28 because maras had kidnapped her son for several days. After the kidnapping and further threats, they decided to flee. She explains they had planned to stay in Mexico, but after reaching Chihuahua, Chihuahua they received a message through Facebook, saying, “We know you crossed, we’ll be waiting for you there.”

At that point she had to separate from her husband, and went to the border to turn herself in with her son. She has not heard from her husband, but is hopeful that he managed to enter the U.S. “The hardest part is when my son cries at night and asks for his father and I don’t know what to say.”

Sandoval is shy but slowly opens up, recounting the details of her chilling journey through Mexico to reach the U.S. border. Her two children are in the adjoining living room, drawing with some of the other children staying at the house.

She fled Guatemala because the domestic abuse she suffered at the hands of her husband had become unbearable.

She arrived in Mexico with her two children and no money to pay a coyote. In Tapachula a man offered to help them head north. Instead he took them to his home, along with a Honduran woman. For the next eight days, she was trapped in the home and the man raped her and the other woman. One day when he was out getting food, they escaped.

Sandoval knows that the process to receive asylum will be long and challenging but she says, “I’d rather fight against the American justice system than the father of my children.”

The majority of women arriving in Dilley and Karnes have survived extortion, rape, domestic abuse or threats against themselves or their children. Despite their genuine fear to return to their home countries, without pro bono projects such as CARA, few would ever have a lawyer to represent their asylum cases.

On asylum and deportations

Building on the experience in Artesia and seeing a tremendous need for legal representation at Dilley, four immigration organizations banded together in March 2015 to form CARA, the pro bono legal aid project that represents hundreds of clients on a weekly basis. RAICES, the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA), the Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLINIC) and the American Immigration Council make up CARA. RAICES also provides legal support at Karnes.

An innovative rotating volunteer system and a carefully-organized database allow CARA to take on the cases of a staggering number of detained families. Most pro bono law projects have a one-to-one lawyer-client framework. Lawyers take on individual cases and represent them from start to finish.

As Attorney Stephen Manning describes, the first lawyers to arrive at Artesia made the strategic decision to represent everyone in detention: “After all, if we represent everyone in the facility, we immediately become a player at the table because our ability to defend en masse was a direct counterweight to the government’s ability to deport en masse.”

As Attorney Stephen Manning describes, the first lawyers to arrive at Artesia made the strategic decision to represent everyone in detention: “After all, if we represent everyone in the facility, we immediately become a player at the table because our ability to defend en masse was a direct counterweight to the government’s ability to deport en masse.”

At CARA, new volunteers stream in every week and pick up the pre-existing cases. This is possible through a database designed by the Innovation Law Lab, which allows CARA to track hundreds of individual cases at any given time.

One week in April, a handful of volunteers managed to prepare 175 women for their Credible or Reasonable Fear Interview and complete in-take on 150 new cases.

Those who do not pass the interview are subject to deportation. The CARA project advocates in their cases for a second interview or review with an immigration judge, which in most cases is successful. That same week the team was also working to help several women prepare for a second interview, or appeal of their negative decisions.

An ongoing challenge for CARA and other immigration and asylum lawyers around the country is representing clients whose persecution in their home countries does not easily fit into the defined asylum categories. Asylum can be granted on the basis of persecution due to religion, race, political affiliation or membership in a particular social group. Most cases from Central America and Mexico are qualified as persecution based on a social group, yet case law is limited.

The most notable pattern so far this year has been the increase in Mexican cases. In the first three months of 2016, they had provided legal assistance to 100 Mexican families, almost all from Michoacan, Guerrero and Oaxaca, fleeing cartel violence or land disputes. From early March 2015 to the end of 2015, a span of nine months, the project worked with only 40 Mexican families.

Managing attorney Katie Shepard explains the extra difficulties of defending Mexican families, “There is less case law on Mexican cases, and it is often hard to prove who the persecutor is in these cases.”

Mexicans are deported to the border without consulting the Mexican consulate, unlike Central Americans whose travel documents must be arranged with their consulate, buying time for the lawyers. “It takes an hour and twenty minutes to deport Mexicans,” says Philabaum, his voice weary with experience.

For-profit family detention

Corrections Corporation of America, or CCA, operates Dilley, in addition to over 65 other detention and corrections facilities around the U.S. The GEO Group runs the Karnes facility. Family detention is a big business: According to Homeland Security data, each detainee costs the federal government $343 a day. By that estimate, for the 900 detainees currently in Dilley, the federal government is footing a bill of over $300,000 every day.

Press access to private prisons is notoriously difficult. This reporter’s request for a tour or interview with ICE was denied. Stories of conditions inside the facility trickle out as women talk to the press upon release, or from CARA members organizing online campaigns based on their clients’ complaints.

CARA organizers are particularly concerned that CCA is seeking to certify the facility as a child care center with the state of Texas, as they receive complaints on a daily basis about the low quality of child care provided. There have also been allegations of sexual assaults at the Karnes facility.

Due to fracking in the region, the tap water in Dilley and Karnes is contaminated. However, this is the only water provided to the women and they otherwise must buy bottled water.

Misinformation about their legal rights is the norm and without CARA, women would remain ignorant to their asylum cases. Philabaum says, “The ICE officers continue to maintain this horrible grip of fear over these women. It’s a continuation of the fear that pushed them to leave their country in the first place.”

Villegas recounted how one night at Karnes her son was sick, but a guard started shouting at him and grabbing him by the arm. She reported the incident and says, “We come here to escape violence, and then for someone to treat us the same way, that’s wrong.”

In 2016 CARA has noted an up-tick in the number of very young children and babies detained in the facility. During March alone, CARA tallied 101 children under 2.5 years in detention. It’s a common sight to see mothers breast-feeding or volunteers attempting to calm a crying baby so his or her mother can enter a legal consultation meeting.

Next stop: a back-logged immigration system

Families who have been released from detention have only crossed the first hurdle to receive asylum in the United States. For most, the first stop after leaving detention is the San Antonio Greyhound station, or the small airport on the north side of town. From there they travel to be re-united with family members around the country: Atlanta, Dallas, Maryland, Arkansas.

RAICES works to provide short term housing at the Casa for some families. Some are waiting for the money to buy bus or plane tickets. Others have to undergo medical procedures before traveling. Multiple women this year have had abortions in San Antonio, after being raped during their journeys to the U.S.

RAICES attorney Andrea Meza has also worked to create a network to connect women with lawyers around the country. Yet in researching options, she quickly found, “For the women who have been released, there is such a huge need and such a dearth of services.”

Unaccompanied minors who arrive in the U.S. often have access to pro bono lawyers and other services, yet Meza says, “For whatever reason our government has determined that… …if you throw an adult into the equation, therefore you don’t need services.”

Even though these families have already proven they have legitimate asylum claims, Meza says, “People are left vulnerable without resources.”

What’s next for family detention

Hutto and Artesia were both shut down as family detention centers after campaigning by lawyers and activists. The legal projects at Artesia and Dilley have always been intent not just on alleviating the suffering of detained families, but ending family detention for good.

Manning writes, “The volunteer project became a change agent aimed at shutting down Artesia. The lawyers realized then that the best way to shut Artesia down was to win cases. A lot of them.”

While the rate of deportations has plummeted since the entrance of pro bono projects, hundreds of families continue arriving in Dilley and Karnes every week. They arrive at the discretion of ICE, because under U.S. law there is no imperative to detain them.

CARA project and other advocates say the government considers the mass detention of families a method to deter other Central Americans from attempting to cross the border. They say the immigration raids targeting recently-arrived families in January were another deterrence tactic. CARA Project Assistant Alex Mensing states, “Yes, there are women who have heard about the raids, but they keep coming anyway. It’s face death at home or come here.”

While the Southern Border Plan in Mexico has blocked many Central Americans from reaching the U.S. border, they continue to arrive out of desperation. The Northern Triangle has suffered some of the worst violence in memory this year, expelling hundreds of people on a daily basis. President Obama insists that his immigration enforcement and deportation targets immigrants with criminal backgrounds. Yet his secret swept under the rug in rural Southern Texas is that thousands of women and children have been sent to detention when they seek asylum in the United States.

Family detention has not surfaced as a topic of debate in the Presidential campaigns, but whoever follows Obama in the White House will have to decide whether or not to continue this legacy. Meza insists, “There needs to be an actual solution instead of this deportation machine.”

Martha is a journalist based in Mexico City, covering politcs and culture in the Americas. She is a former Fulbright scholar and originally from Washington, DC. This piece forms part of the En el Camno project of the Red de Periodistas de a Pie with support from Open Society Foundations. enelcamino.periodistasdeapie.org.mx