One year ago, the disappearance of 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Normal School brought human rights abuses in Mexico to the international spotlight. A year later, and despite an extensive investigation by the federal government, the case remains mired in impunity and deception.

One year ago, the disappearance of 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Normal School brought human rights abuses in Mexico to the international spotlight. A year later, and despite an extensive investigation by the federal government, the case remains mired in impunity and deception.

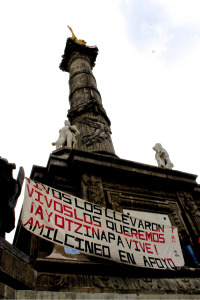

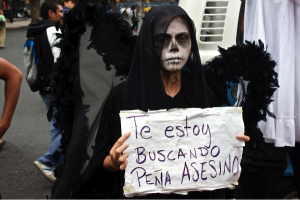

On Saturday, Sept. 26, which marked the first anniversary of the disappearances, at least fifteen thousand supporters representing a broad cross-section of Mexican society marched in the capital demanding justice for the students. Marching in contingents, organizations including student collectives, teachers’ unions, indigenous organizations, leftwing political parties and Zapatista supporters showed their support for the families of the disappeared.

The march started at Los Pinos, Mexico’s presidential palace, and followed a more than five-kilometer route to the city’s Zócalo, where it ended with a rally. In spite of heavy rain showers, thousands of people crowded around a stage in the Zócalo to listen to the speakers.

Vidulfo Rosales, a Guerrero native and human rights lawyer who serves as the legal representative for the families of the 43 disappeared students, was the master of ceremonies for the rally. He argued that the focus of the movement should be expanded to encompass increasing demands for social change in Mexican society.

“We reiterate and ratify our promise to the families of the rural teaching college,” Rosales said. “We are ready, and we have the conviction, to create a broad front that can bring about a radical transformation of this country. Because we are tired of the oligarchic governments. Because we are tired of the tyrants that never cease trampling on us, that never cease dispossessing us.”

The march came days after the release of a report by the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) from the Interamerican Commission for Human Rights (IACHR) on the events of Sept. 26 and 27, 2014. The experts’ report showed that the Mexican government’s investigation contained many troubling inconsistencies. In particular, the experts found that the government’s claim that the 43 students were incinerated at a garbage dump in Cocula, Guerrero is scientifically impossible.

The findings in the long-awaited report fueled the anger and mistrust of the government that has been at the core of the movement for justice in the case of the murdered and missing students. The inconsistencies have led the families of the disappeared to ask whom the government investigators could be protecting.

At the rally, parents of the disappeared students addressed a packed plaza under a summer rain, expressing their rejection of the findings of the government’s investigation. With the theory of execution and incineration discarded, many believe that their sons could still be alive.

“We will not allow this case to be closed,” said Melitón Ortega, the father of Mauricio Ortega, one of the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students. “Even though that is what the government is trying to do in all sorts of ways, trying to impose their ‘historic truth.’”

The central demands of the movement and the demonstration were that the forty-three students be returned to their families alive, that there be a full investigation into the crime and that the guilty be punished.

Although the march’s focus was demanding justice for the students, many participants criticized the government’s neoliberal structural reforms, especially the reform to the education system.

The families and their supporters frame the 43 disappeared students not as victims of an isolated action by corrupt government officials, but rather as casualties in a struggle for social justice. Their demands, then, include annulling President Enrique Peña Nieto’s education reform and calling for the president’s resignation. Members of the Mexico City Popular Front (FPCM) carried a banner that read “Down with the neoliberal structural reforms! For Peña Nieto’s resignation!”

The families and their supporters frame the 43 disappeared students not as victims of an isolated action by corrupt government officials, but rather as casualties in a struggle for social justice. Their demands, then, include annulling President Enrique Peña Nieto’s education reform and calling for the president’s resignation. Members of the Mexico City Popular Front (FPCM) carried a banner that read “Down with the neoliberal structural reforms! For Peña Nieto’s resignation!”

José Peralta, a student at CCH Vallejo, a Mexico City high school, sees the educational reforms as an attempt to privatize education. “When Peña Nieto’s educational reforms started, they started to change our form of education—they tried to make more private schools, which many people don’t have the means to pay for,” said Peralta. For Peralta, the attack on the normalistas in Iguala and the educational reform are both part of an offensive against the student sector, which he said makes him feel “anger and sadness.”

Felipe González, a student at the Mexico City University UACM San Lorenzo Tezonco and a member of the José Revueltas Collective, sees the attack on the rural teaching college students as part of an attack on students everywhere.

“The state uses terrorist techniques to put down grassroots protest”,” said González. “Students are the sector that is most affected because they are the most critical, especially from the rural teaching colleges, which have suffered attacks for a long time.”

At the rally, representatives of grassroots movements offered their solidarity with the families of the disappeared and emphasized the unity of their struggles. After an introduction from Rosales, Hipólito Mora, a founder of the Self-Defense Groups of Michoacán, addressed the crowd.

“The criminals are free in the street. The innocent are in jail. Forty-three kids are disappeared. I am in the same situation as the parents of the 43 kids. I also lost a son in this struggle,” Mora said to the crowd, who applauded his messages of solidarity and jeered when he spoke of the current government.

“We need to fight against this bad government that is always trying to censor us, that has imprisoned us—in my case twice. There are still 380 members of self-defense groups in prison, and the government doesn’t want to release them. They don’t want to release them because they are people who in some way affect the interests of the thieves who rule our government.”

Mora ended his speech with a plea: “Please, ladies and gentlemen, let’s unite on the same side of a unified struggle.”

Rosales closed the rally with an invitation for civil society to come to the fourth meeting of the “National Popular Convention” at the Normal School of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. The convention will take place in mid-October.

“Civil society organization will allow us not only to find the students, but also to confront the structural reforms,” Rosales said. “It is necessary that there be no more isolated struggles.”

Simon Schatzberg is an intern for the CIP Americas Program

Photos by Simon Schatzberg