The denunciations state that most of the attacks are promoted by the government and its officials. Additionally, attacks made against female journalists include highly misogynistic and hateful content.

The denunciations state that most of the attacks are promoted by the government and its officials. Additionally, attacks made against female journalists include highly misogynistic and hateful content.

Journalism in El Salvador is experiencing levels of hostility not seen since the 80’s, during the country’s bloody civil war. Threats, persecution, and false accusations against journalists are increasing in a country that paid for its young and fragile democracy with over 75 thousand lives.

For the first time in the 29 years since the signing of the peace accords, a president and several members of his cabinet have been called out for their repressive actions and for inciting violence against critics, in ways that echo the military governments of the 1980s.

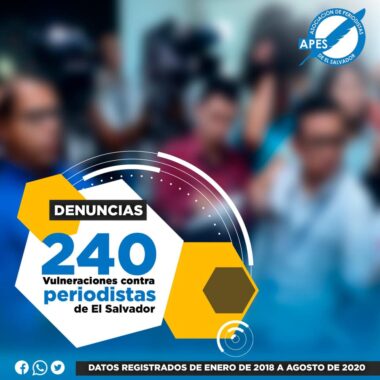

Last week, the Association of Journalists of El Salvador (APES) presented its report on attacks on journalists, freedom of expression and freedom of the press. According to the APES report “Freedom of Expression in El Salvador 2020”, aggressions against journalists doubled between March and September of that year. The organization registered 125 cases in 2020 and 77 in 2019, while in 2018 there were 65. The main culprits of threats and aggressions against journalists and media included President Nayib Bukele and several officials of his cabinet.

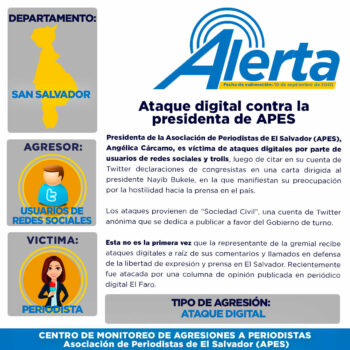

“Threats made via social networks are a trend since the 2019 elections. Most of the digital attacks come from officials, led by President Nayib Bukele, who has also been dedicated to blocking users, journalists first and foremost. He is followed by his officials, also by government supporters and anonymous accounts,” said the president of APES, Angélica Cárcamo.

On July 2, Julia Gavarrete, a journalist with Gato Encerrado magazine, became a target. The journalist left her home for a last-minute press conference convened by the Ministry of Health (MINSAL). The event would be the only opportunity to hear from government officials authoritative figures regarding positive Covid-19 cases in the country. Thus far, this information has been closely guarded among State institutions.

“That day, they were going to publish data that they do not officially publish and that the Ministry of Health had. I found it curious that when I arrived I insisted to sign up for the list of questions and they told me no, after insisting, almost at the end of the conference, they asked the press secretary (Ernesto Sanabria) and he nodded his head and I was able to ask my question,” Gavarrete told Américas Program.

Gavarrete recalls that the conference took longer than usual. When Julia returned home, she found everything in disarray, her bedroom door was open, her closet drawers were open. Someone had broken into her house. Her laptop and other electronic devices used for work were gone.

“It wasn’t a simple burglary,” the journalist says. The people, or the person who broke into Gavarrete’s house, took nothing but the computer and other work equipment. “Because of the quarantine, I hadn’t been out for three weeks. The person who broke into my house knew where I was that afternoon,” she said.

“Nothing of value was taken. My wallet was at home with money in it and they didn’t take it; they didn’t take jewelry either. They only took my laptop, a tablet, which I normally left on the table where I worked.”

Weeks before the house was broken into, Gato Encerrado published several investigative articles by Gavarrete, exposing cases of corruption and nepotism committed in Nayib Bukele’s first year of government. In addition, the journalist had participated in forums on human rights violations during the country’s quarantine.

Reactions to the publications were immediate. As is now common, journalists or media investigating and publishing information on corruption, nepotism, lack of transparency, and administrative irregularities from the Executive or the constant disrespect of State institutions by President Bukele must contend messages loaded with hate and violence from anonymous troll accounts.

“With each publication we receive digital attacks. In one of the messages, they told me ‘I hope they find you and your family in a body bag’. Sometimes you know they are trolls and sometimes you don’t know if they are real government supporters. But it is dangerous,” said Gavarrete.

In the end, President Bukele downplayed the computer theft from Gavarrete’s home on social media. This led the Human Rights Institute of the Central American University (IDHUCA) and Julia to publicly denounced the incident. But while neither the Gavarrete nor the UCA singled out anyone in particular during a press conference, President Bukele felt alluded to and reacted on his twitter account stating:

“The UCA gives a press conference accusing the government of stealing a laptop. It seems like a joke but it is not.”

Attacks on journalists on the rise

During the first year of Nayib Bukele’s government, reports on the attacks against journalists increased considerably. The Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) noted in its latest report that during 2019, attacks, threats and lack of guarantees for the work of journalists in El Salvador were on the rise.

The report also highlighted that “independent media denounced selective inspections of sites critical of the current government, violations that are consolidated contrary to the environment conducive to the normal development of journalistic practice in the country”.

Julia Gavarrete’s case is one of the more serious incidents, but there are more. The same month, the independent news media Focos, denounced “incessant expressions of harassment and hate” against journalist Karen Fernandez, for criticizing the government. Messages with highly misogynist and hateful content against women journalists were republished by government officials, members and candidates of Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party.

Congresswoman Karina Sosa pointed out in a conversation on the political situation in El Salvador that took place with civil organizations in the United States at the beginning of September, that the increase in attacks against journalists, especially against female journalists, prompted by the government is concerning.

“We have observed an increasing number of attacks and we are concerned that the attacks on women journalists are worse than the attacks on male journalists. These attacks are loaded with a message of hate and misogynistic violence against women journalists. We have seen messages in which these accounts tell women journalists that they are going to rape them and we find this very worrying”, said Sosa.

APES data point out that between January 2019 and August 2020, 80 women journalists have been victims of violations and attacks. The organization’s president, Angélica Cárcamo, also points out that these violations are more evident when it comes to female journalists and that most of the attacks are promoted and encouraged by President Bukele and senior officials of his government.

“There is an intention to stigmatize journalists who criticize or who do not follow the government’s pro-government message. We are concerned that the president or his officials promote messages of discrediting or defamation against journalists and that the attacks against women journalists have a misogynistic component,” Cárcamo told Boletín Américas.

In early September, the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, chaired by Congressman Eliot Engel, sent a letter to President Bukele, questioning “the government’s increasing hostility toward independent and investigative media.”

In early September, the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, chaired by Congressman Eliot Engel, sent a letter to President Bukele, questioning “the government’s increasing hostility toward independent and investigative media.”

A few days before Republican and Democratic senators sent the letter, Bukele instigated a series of attacks against journalists from El Faro, one of the most prestigious investigative media outlets in Central America. The smear message against the journalists was replicated on pro-government websites and on the accounts of government officials. In response to the president’s public accusations against El Faro and the lack of follow-up on accusations of gender violence in his own government, the Mesa de Protección a Periodistas published a communiqué under the title: “Gender violence must be investigated and prosecuted; it should not be instrumentalized nor should there be any sort of revictimization”. Among the cases that remain unpunished are the accusations of violence against women made against Bukele’s press secretary, Ernesto Sanabria.

Attacks against me

In January 2020, I joined the list of female journalists attacked by Salvadoran government officials and their supporters.

It was in this month that I published an article that highlighted the criminal proceedings for violence and threats against women made by the press secretary of the Presidential House of El Salvador Sanabria. Official court documents show that Sanabria sentenced his ex-partner and threatened her: “I’m going to kill you and no one will notice where I’m going to bury you”. According to the testimonies recorded in court, Sanabria intimidated her and prevented his ex-partner from reporting him, stating that: “I bought justice in this country. I did not kill you because I am going to be the first suspect”.

This story and other publications on denunciations of women journalists who are victims of sexual harassment in the media in El Salvador that I reported in November 2019 triggered attacks against me that were prompted by the press secretary in three distinct moments.

The latest attack took place the first week of last August. Sanabria accused me of slandering President Bukele, spreading hate messages against the Salvadoran government and sowing disunity among Salvadorans. Several social media accounts reproduced Sanabria’s hate messages. One of them declared me “enemy of the country and the color turquoise”, the color that represents President Bukele’s party. In addition, they used the domestic violence case of which I was a victim of to humiliate me.

My photograph was exposed, false information was spread about my immigration status and about an alleged investigation against me in the United States by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). A few weeks after the attacks began, the media outlet that published the articles about harassment against women journalists and the cases of violence, threats and physical violence by Sanabria, unpublished the stories.

Alarms and concern

Alarms and concern about the situation of journalists in El Salvador are starting to be raised. The Inter American Press Association (IAPA) also repudiated the threats and attacks instigated by President Bukele and his government against journalists and pointed out that “the increase of attacks, the tension with the presidency, the selective blocking of public information and the use of pro-government trolls to denigrate the critical work and independent press”, are worrying.

Additionally, the IACHR Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, Edison Lanza repeatedly expressed his concern in interviews and on social networks:

“The levels of stigmatization of media and journalists in El Salvador by officials has reached staggering levels. They do not resort to debate or accountability, but to diatribe and disqualification from power. The IACHR Rapporteurship is following these actions,” Lanza tweeted.

The Salvadoran Legislative Assembly authorized at the end of August the creation of a special commission to investigate attacks on journalists and the use of public funds to finance these attacks. The group of deputies has interviewed members of APES, journalists who have been victims of attacks and aggressions, and the Human Rights Ombudsman, Apolonio Tobar.

After 15 meetings with 26 journalists, the commission concluded that Bukele’s government uses state resources to promote and carry out attacks against journalists and media critical of his administration.

“In El Salvador there is harassment, discrimination, insults and mistreatment of journalists by the Executive Branch. There is a blocking of public information and access to public officials to certain media that are critical of the current administration”, said Congressman Emilio Corea, member of the commission that investigated the attacks.

However, the conclusions of the report do not include actions that could be taken to avoid further aggression against journalists and only recommend the government to stop the attacks. The Salvadoran Attorney General’s Office confirmed that there are reports of journalists and media outlets that have been subjected to threats, attacks on freedom of expression and coercion, but none of these cases have been taken to court.

Carmen Rodríguez is a journalist in San Salvador specializing in issues of security, justice, migration and international relations. She has been a contributor to The Americas Program since 2014.